Vance Monument is showing its age.

Streaks of rust run down the foundation. Gouges mar the plaque’s lettering. The bricks are faded and cracked, washed out and weatherworn, attesting to the changes they’ve seen.

Erected in 1897, it’s been around for more than a century. The cornerstone was laid at a public ceremony in a packed town square. The Rev. R.R. Swope addressed the crowd, the Asheville Citizen reported, couching his remarks in lofty rhetoric: “Its granite shall be as strong as [Vance’s] character. Upright as was his memory, this shaft shall stand as an enduring witness. … May his name and fame be as a beacon prompting to patriotism in the land of his birth and his love.”

The towering obelisk still stands tall in the center of downtown, dominating Asheville’s center of power. The Buncombe County Courthouse and City Hall reign at one end; the monolithic BB&T Building looms over the other.

At press time, restoration of the monument was slated to begin in early April, managed by the 26th North Carolina Regiment, a Civil War re-enactment and historic preservation society. (Vance commanded the 26th North Carolina Regiment in 1861.) The project is expected to take three to four weeks, with a rededication ceremony to follow on May 16.

But there’s another side to this story.

“For me, as an African-American, it’s on par with memorializing Nazis as a Jewish person. I’m just never going to be OK with it,” says Dwight Mullen, a political science professor at UNC Asheville.

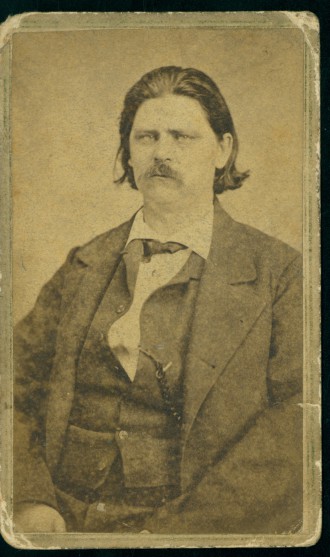

By many accounts, Zebulon Vance was a white supremacist, a fairly common stance at the time. He served the Confederacy as a military officer and wartime governor. He also supported and profited from slavery.

Gordon McKinney, the author of Zeb Vance: North Carolina’s Civil War Governor and Gilded Age Political Leader, says historians haven’t found a direct connection between Vance and the Ku Klux Klan. But Vance, notes McKinney, a history professor at Berea College in Kentucky, certainly benefited from the secretive militant group’s work to suppress the votes of political groups overwhelmingly opposed to his election as governor.

Defining “good”

Mullen, meanwhile, remembers when his son, after a school field trip to the Vance Birthplace, asked, “What’s wrong with Zebulon Vance? The lady says he was good to his Negroes.”

“At that point,” Mullen recalls, “I said, ‘You know, we might have different definitions of good.’”

But what’s the solution? Do we just let the monument crumble?

“Yes, I would,” says Mullen. “I think it would be a really powerful statement. Just let it fall down; leave it right where it drops.”

Darin Waters, an assistant professor of history at UNCA, says Vance’s character must be considered in the context of the times. “Vance advocated religious tolerance, particularly toward Jews. He served North Carolina fully and faithfully as its governor, making hard decisions on behalf of its residents — its free residents. He was complex, if nothing else.

“We don’t always like to see the complexity of that history,” continues Waters. “We like a clean narrative — a narrative that tends to promote the idea of triumph and progress.”

Upon Vance’s return to office in 1876 after an 11-year hiatus, his first major project was extending the North Carolina Railroad, a largely state-funded enterprise whose construction had stalled at Old Fort before the war, to Asheville.

According to McKinney’s book, Vance foresaw the railroad’s potential economic benefits for the Asheville area, adopting the cause as his personal crusade.

“Of course, Vance was from Asheville,” says McKinney, “and he and his family owned a lot of land in Asheville, which, if the railroad got here, that land would be worth a lot of money.”

At the time, African-Americans could legally be rounded up, convicted on trivial charges such as unemployment and vagrancy, and then leased out to industries by the government. This supplied states with forced labor without meeting the legal definition of slavery.

North Carolina lacked the funds to complete the railroad, so Vance deployed an initial workforce of 250 convicts, with more to follow as the operation continued. The railroad was indeed completed, and the area prospered — but 125 convict laborers died in the process, some from exposure and starvation in the harsh conditions, some from accidents and cave-ins. Others were simply shot as they tried to escape. And when Vance was notified of these deaths, he demanded that the work continue at the same pace.

“African-Americans,” says McKinney, “were arrested for vagrancy and loitering, and things like that — which turned out to be a death sentence.”

And while the author says he knows of no commemoration of those deaths, there are numerous dedications to Vance across the state. Over time, he became a symbolic figure for the “lost cause” of the Confederacy in North Carolina; groups such as the Southern Historical Society and the Daughters of the Confederacy sanctified men like Vance, romanticizing the Confederacy’s cause and leaders.

“I really do have issues with the memorialization of the Confederacy,” says Mullen, “because somehow it’s disassociated from slavery. And no, you’re memorializing slavery. That’s what you’re doing.”

Col. Chris Roberts, commander of the 26th North Carolina Regiment, declined to comment on the controversy.

Filling in the gaps

Deborah Miles, the director of UNCA’s Center for Diversity Education, says Americans are often reluctant to take a critical view of the nation’s history. But tearing down the Vance Monument or letting it fall, she believes, would cause too much dissension. Instead, a new memorial — as iconic as the Vance obelisk and equally prominent — should be established, paying tribute to the African-Americans of Western North Carolina, including those who gave their lives building the railroad. As of February, a petition for the cause had collected over 1,000 signatures.

Waters, who supports the proposed monument, says it’s really a matter of picking your battles.

As one of Asheville’s most iconic landmarks, the Vance Monument is almost certainly here to stay. But Pack Square, notes Waters, is a public space of power, and it’s important to consider what ideals and what history it reflects — and also what is absent.

To most visitors, notes Sasha Mitchell, chair of the City-County African American Heritage Commission, the Vance Monument is probably just a piece of scenery. But for those who know more about Zebulon Vance, particularly Asheville’s African-Americans, having such a prominent dedication can send a powerful and troubling message.

“I think it’s worthy of looking very carefully at possibly making a change to the monument,” she says. “I know that’s touchy, because you want to preserve history. On the other hand, we’re not static.”

To further compound the muddle of negative associations to Vance, the Reconstruction Period and Jim Crow Laws, I believe I’ve read that the now-closed public restrooms, at basement level, beneath the monument, were marked by signs: “Whites Only”. Those doubtful may carefully observe the photograph at the top of the article, where a man may be seen descending the stairway at the left of the monument. Many times, while passing Pack Square, I’ve wondered if those restrooms still exist, as a sort of sealed tomb, or if they were filled with rubble during modernization. Anybody know ?

“…the petition asserts that, with the abundance of Confederate heritage markers in downtown Asheville…”

What abundance? I am only aware of three in Asheville, and two are NOT downtown (one on tunnel road commemorates a post-Civil War school named after one of the Lees, another at UNC-A denotes a skirmish that is laughingly called “The Battle of Asheville”). The only downtown marker I know of is near Battery park and is about the artillery battery that it was named after. Even if you consider the Vance Memorial a “civil war marker”, that makes TWO, hardly an “abundance”.

I grew up in the city of Asheville and I feel very proud of that fact. I grew up in West Asheville. I remember walking past the monument several times when I had the priviledge of going to the downtown area. This was a land mark that will catch the attention of any young boy. Me, being an older black man, did grow up in a segregated world. I know what racial descrimination is. This is a very tricky subject. I can understand why people would not want to delegate any tax dollars to comemerate a slave owner, but there were several slave owners during that period. Not all owners were as bad as we imagine. I live in Nashville now and there are a few monument here that pay tribute to slave owners. I think that these people are a very important part of “our” history. I don’t believe in trying to wipe out the past. Keep the monument and instead of putting a negative spin on it, make it a positive one. I am sure he has done a lot of good things when serving as the Governor of North Carolina and that maybe the thing we all need to remember when we walk past that monument.