A moment in 2012, when Preston Blakely was a senior at Asheville High School, would prove pivotal to voters in Fletcher nine years later.

“I was turning 18 at the end of October, and Election Day was coming up, and I would finally be able to register to vote,” says Blakely. “I remember voting for Barack Obama for his second term. It was super exciting to me that I got to vote for him — somebody looked like me — to be president of the United States.”

The civic-minded youth was inspired to run for office himself. And today, at 27 years old, Blakely serves as the mayor of Fletcher after winning election in 2021 with 55% of the vote — making him the youngest mayor in the town’s history. Blakely is Fletcher’s second consecutive Black mayor following the retirement of Rod Whiteside.

Blakely says his win in a town where just 4.1% of the population is Black represents a dream realized. But he also acknowledges the painful history that Black politicians have experienced, as well as the present-day challenges that still plague them.

“I think anytime we see Black leaders getting elected in places like that, I think that’s something to be optimistic about. I hope that trend continues, because Black folk have been historically excluded and underrepresented in these positions,” Blakely tells Xpress. “I think we have come really far. But obviously, we have a long way to go.”

Legacy of leaders

Western North Carolina’s history of electing Black leaders stretches as far back as the post-Civil War era. Asheville’s first Black elected official was Newton Shepard, who was born into slavery in 1841 and won a seat on the city’s Board of Aldermen, a precursor to today’s City Council, in 1882.

But a long gap would ensue until Asheville chose another Black representative: Ruben Dailey, a civil rights and anti-segregation attorney elected to City Council in 1969. More followed, including Wilhelmina Bratton, Asheville’s first Black woman to serve in the role of vice mayor, from 1982-91. In 2005, Terry Bellamy was elected as Asheville’s first Black mayor and served until December 2013. Keith Young was elected to Council in 2015, followed by Sheneika Smith, who’s currently serving as vice mayor, in 2017.

Following a vacancy left by the resignation of Council member Vijay Kapoor, Black attorney Antanette Mosley was appointed to Council in fall 2020. And in that year’s election, Asheville picked Black real estate agent Sandra Kilgore as part of its first all-female City Council, with three of seven seats occupied by Black representatives.

For his part, Blakely recognizes Fletcher’s former Mayor Whiteside, who was elected in November 2017, as blazing the trail before him. “I’m incredibly grateful for Mayor Whiteside,” he says. “Without him, I’m not even sure I’d be in the place that I am today.”

A desire for change

Part of what contributed to Blakely’s early interest in politics, he says, was his relationship with his grandmother, renowned civil rights leader Oralene Simmons. As a child, he used to compete with her in a Black history trivia game and researched other past Black leaders to gain an edge.

Although she used to live live in Mars Hill, Simmons recalls being bused to go to school in Asheville, about 20 miles away, because schools were segregated. She attended Stephens Lee High School and became active with the Asheville Student Committee on Racial Equality, which helped to integrate the public facilities of Asheville and Buncombe County. She later returned to Mars Hill and became the first Black student at Mars Hill College.

“My activism came about with having experienced injustice. I wanted to bring about a change,” Simmons says. “That’s what caused me to start thinking about civil rights, because I realized that injustice at a very early age, walking miles to a bus stop.”

For Asheville City Council member Kilgore, although her family discussed politics while she was growing up — she calls her father a “very active armchair politician” and voracious news consumer — she didn’t intentionally seek out the arena. Instead, she felt motivated to get involved because of what she saw as a lack of inclusion among the Black community.

“It was more out of a void I saw within the Black community in Asheville and throughout the country,” she explains. “The presence of an opportunity and identified need resonated with me.”

Former Asheville City Council member Young says he decided to run for elected office after serving as the second vice chair for the Buncombe County Democratic Party. He remembers a discussion among party’s leaders before the 2012 election cycle as a turning point in his aspirations.

“People were being named, and they were all white, with mostly little to no service to the party or real political acumen,” says Young, who also works as a deputy clerk of Superior Court in Buncombe County. “I realized no one who looked like me — a Black man — or really understood the lived experiences and issues of the BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and people of color] community and the most vulnerable will ever serve in office as long as these people are playing a rigged game. I was the change I needed to see.”

Young says he immediately resigned his position in the party and campaigned to become the first Black Buncombe County commissioner. He lost that election but went on to win a City Council seat in 2015. (Al Whitesides eventually became the county board’s first Black member after being appointed to fill a vacancy in 2016; he was reelected in 2018 and continues to serve.)

He cites members from his church, Hopkins Chapel AME Zion in downtown Asheville, and his father, William Henry Young Jr., as being mentors to him during his campaign. Young says he also received guidance and support from the late local civil rights activist Isaac Coleman.

Young is forthright about his motivation to serve. “Not seeing anyone recognize or care about the Black community in office influenced me,” he says. “My community was too busy trying to survive to worry about politics.”

Progress?

Despite Blakely’s historic win in Fletcher, his campaign for mayor was marred by issues similar to those that have faced Black politicians for decades. Just days before Election Day, anonymous flyers were distributed labeling Blakely, a Fletcher resident for more than 20 years, an “Asheville Democrat” and “a liberal-progressive who wants to make Fletcher more like Asheville.” The flyers also said that Blakely supported “the urbanization of Fletcher, low-income housing and a racially based allocation of government resources,” which the candidate took as an attempt to stir up opposition based on his race.

“When I saw all those flyers, I was incredibly disheartened. Like, incredibly. I sat in my car for a little bit when I found out,” Blakely remembers. “This wasn’t just a dog whistle — it was a bullhorn.”

Racism toward Black politicians has always existed, says Young. “There is always doubt if you will be effective or know what you’re talking about, even if you are the smartest and most knowledgeable in the room,” he says. “The stereotypes of Black men being a threat will rear its ugly head.”

Blakely says that the fear of being stereotyped came into play when, while campaigning, he found himself knocking on doors to speak directly with voters.

“When the sun starts going down, I go inside. Because at the end of the day, I’m still a Black man,” Blakely says. “I think obviously, the country has a long way to go. Like I said, I’m always conscious and aware of my race and how that impacts my day-to-day life.”

Leaders of tomorrow

As residents continue to elect Black leaders like Blakely, Young and Kilgore, Asheville’s youth, including 15-year-old Solomon Harrison, are paying attention.

“It means a lot to me. It shows that people who look like me are able to take on that responsibility in a place of power,” says Harrison, a Black ninth grade student at Asheville High School. “It’s just inspirational.”

Harrison participates in the Racial Equity Ambassadors Program, a youth-based initiative for Asheville High School and School of Inquiry and Life Sciences at Asheville that helps students develop advocacy and leadership skills. The program is a collaboration among the Asheville City Schools Foundation, Asheville City Schools and The Equity Collaborative.

While Harrison says he doesn’t have any intention of running for office at this point — he’s more passionate about math — the experience has taught him how to engage with local government to help the community.

“I think it’s really important to recognize this beautiful leadership pipeline within our community,” adds Copland Rudolph, executive director of the Asheville City Schools Foundation. “We’re hoping that the REAP program, in addition to all the other great work that happens in the Asheville City High Schools, is part of creating this pipeline of strong young leaders who will guide our community into the future.”

Another youth-based ACSF program, the City of Asheville Youth Leadership Academy, offers Asheville and Buncombe sophomore and senior high school students paid internships at local government offices. Since 2007, students have been placed in opportunities such as Asheville’s Equity and Inclusion Department, Buncombe County’s Family Justice Center and communications and community development departments in both jurisdictions.

Alex Mitchiner, who directs the program, says students who work up close with local government learn that civic participation makes a tangible difference. She also believes that the program encourages students to pursue jobs in local government — Mitchiner, the workforce development programs coordinator for the city of Asheville, is herself a product of the CAYLA program.

Part of her work is making sure students feel as if their voices are heard and that they share their perspectives on issues that impact them and their community. “Kids are always tuned in to things, and their perspectives are so unique that they make me really kind of step back and go back to the drawing board and have to think about things from a different point of view,” Mitchiner says.

Words of encouragement

Civil rights leader Simmons says that young people who are interested in activism, civil service or leadership should start by learning about the issues their communities face and connect with like-minded people of all ages.

“First off, they should want to bring about a change. They should seek out different campaigns and different issues that are affecting the lives of others or people who are people who are in need, whether it’s at school, in the community or government,” she says.

Meanwhile, Kilgore calls today “an excellent time for Black youth to familiarize themselves with politics,” adding that young people should take time to learn Asheville’s rich Black history. “This will set the foundation for developing their purpose, which is vital in setting their path forward,” she adds.

Young emphasizes the importance of youths connecting with current and former leaders — and not being afraid to challenge those leaders when something isn’t right.

“Learn who represents you in elected office. Learn about your representatives and read articles on local issues. Read the newspaper,” he says. “If you don’t see certain things being addressed, don’t be afraid to reach out to them. Ask them what specific policies they have led to change the things you want to see happen. If they really support your ideals, they should be able to point to their own work and not others. Find mentors, Black mentors, close to power or who are active in politics. They are around, and I’m one of them.”

As for Blakely, he hopes that by inspiring youths today, he will help create a more equitable, efficient and effective government tomorrow.

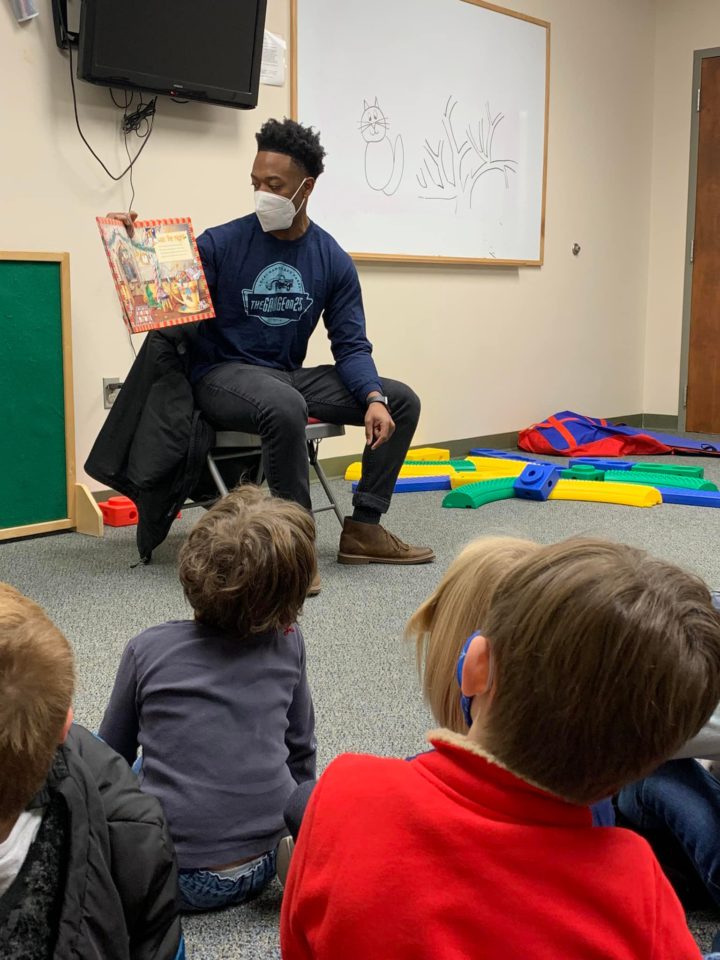

“I think it means something when a Black child looks at me and hopefully imagines themselves as a mayor somewhere, wherever they live,” he says. “I’m more than happy to be a resource for any young person that’s interested.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.