Growing up in Buncombe County, Angel Redmond never thought much about Stephens-Lee High School, the institution that educated Black students in Western North Carolina for four decades until it closed in 1965.

“I did have aunts and uncles who went there, but I didn’t realize how much of an impact Stephens-Lee had,” says Redmond, who graduated from T.C. Roberson High School in 1994. “At Roberson, I learned nothing about it.”

Redmond serves as facility supervisor at the city-owned Stephens-Lee Community Center, which is housed in the school’s former gymnasium. She wants to make sure Asheville’s young people learn about the school that excelled in education, music and athletics and served as a cultural and civic hub for the area’s African American population.

“We try to regularly have conversations with kids at our after-school program and summer camps about the importance of Stephens-Lee,” she says. “We talk about it along the lines of respecting the space that we’re in because this space is so important to Blacks.”

And when alumni of Stephens-Lee reunite at the center this weekend to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the school’s first graduating class, they will be greeted with photos of young people at the community center’s summer camp. It will be one generation’s gift to another, Redmond says.

Active alumni

For the school’s alumni, keeping the legacy of Stephens-Lee alive for future generations is vital, given that even the school’s youngest graduates are in their late 70s.

“We’ve got to uphold this history and we’ve got to pass it on,” says Sarah Weston Hart, a 1957 graduate and president of the school’s alumni association. “We have to encourage our children, our grandchildren, our great-grandchildren, to keep it alive.”

To that end, the alumni association became a nonprofit in the 1990s with a mission to preserve the school’s principles by hosting reunions and awarding scholarships. It has given more than 90 college scholarships to relatives of Stephens-Lee graduates, including Terry M. Bellamy, who served as Asheville’s first Black mayor from 2005-13.

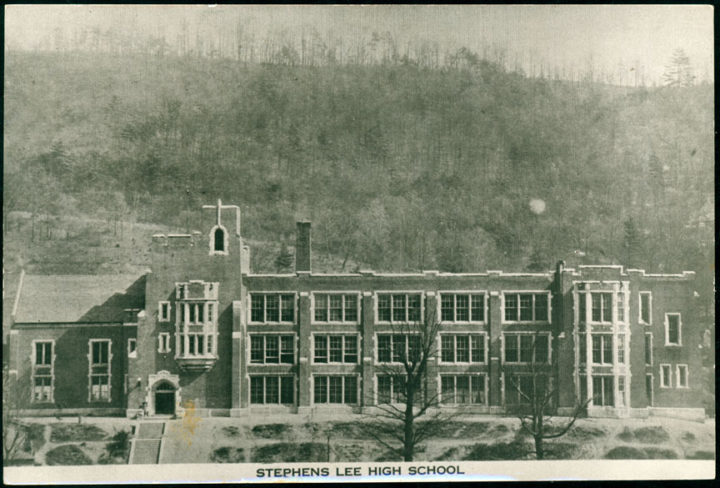

The association also spearheaded efforts to get the Stephens-Lee Community Center designated a local historic landmark in 1996. The center has been the focus of efforts to preserve the school’s legacy because the Gothic-style main building that housed the school, known affectionately as “The Castle on the Hill,” was torn down in 1975.

The center’s main hallway is adorned with personal photos and a timeline of the school’s history. It has a crimson carpet and an archway commemorating the original school building’s entrance. An alumni room focuses on the school’s athletic, cultural and civic history with photos, jerseys, newspaper articles and more.

The alumni room is closed to the general public, but it is a stop on the Hood Tours offered by Hood Huggers International.

And the recently opened Asheville Black Heritage Trail features a plaque commemorating the school. Additionally, the Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority awarded $100,000 to establish an African American Heritage museum at the community center.

100 years later

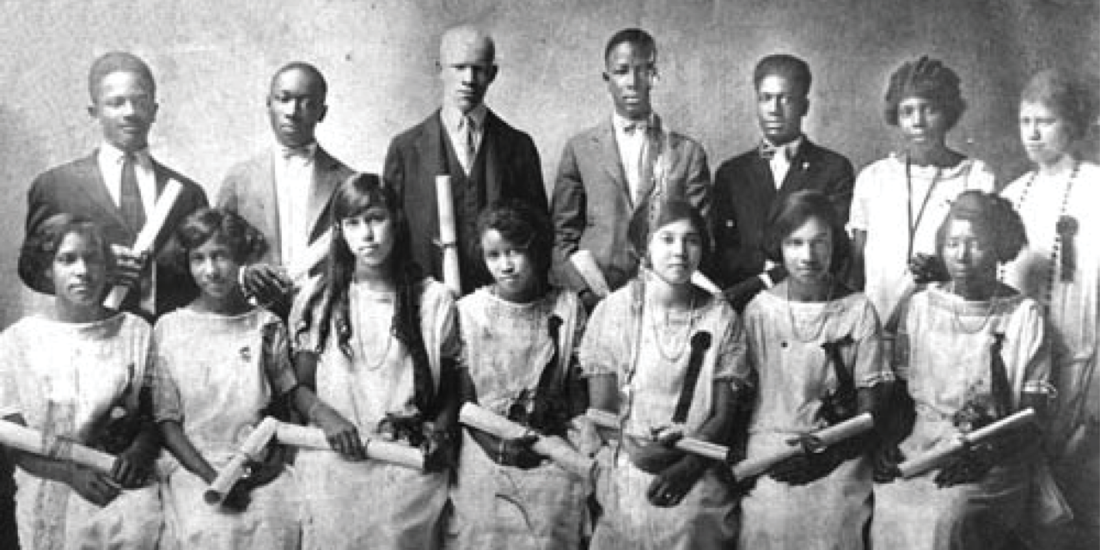

Stephens-Lee High School opened on March 7, 1923, on the site of the former Catholic High School, just above Valley Street in the city’s historically Black East End neighborhood. The school graduated its first senior class a year later, a milestone that alumni from around the country will celebrate from Friday, July 5-Sunday, July 7, at the biennial reunion, themed “100 Years and Still Stepping; (Let us Never Forget) the ‘Castle on the Hill.'”

As Western North Carolina’s only public high school dedicated to the education of Blacks, Stephens-Lee drew students from Buncombe, Henderson, Madison, Yancey and Transylvania counties. Hart, who lived in Mars Hill, remembers taking a bus 32 miles every day on a two-lane road to get to school and back. Some students had even longer journeys, she says.

By 1965, some Stephens-Lee students had been moved to predominantly white schools. That year, the district closed the school and transferred the remaining Stephens-Lee students to the newly built South French Broad High School in the Southside. In 1969, South French Broad’s predominantly Black student body was integrated into Lee Edwards High School, which went back to its original name of Asheville High School.

During its four decades, the school presented band concerts, art exhibits, modern dance recitals, drama and chorus performances that often drew big crowds. The marching and concert bands, led by music director Madison C. “Doc” Lennon, won numerous state awards. Lennon was inducted into the N.C. Bandmasters Association Hall of Fame in 2002.

The marching band, known for its high-energy music, high-stepping drum majors and majorettes, made annual appearances at the Asheville Christmas parade, usually taking the penultimate spot right before Santa Claus made his big entrance.

“They put us near the end because the crowd would always follow our band and not wait for the other part of the parade,” says Richard Bowman, a 1951 graduate who played clarinet and saxophone in the band.

Under the leadership of athletic director C.L. Moore, Stephens-Lee excelled in sports as well. Moore first came to the school in 1935 to serve as football coach. After leaving for a time, he returned in the late 1940s and coached multiple sports until the closure in 1965.

Moore’s success as a coach made him a legend in high school athletics. His Bears won the 1957 state football championship and the 1962 title in basketball, and he sent more than 100 students to college on athletic scholarships. He was inducted into the WNC Sports Hall of Fame in 1983 and the N.C. High School Athletic Association Hall of Fame in 1992, the year he died.

In 1960, some politically active Stephens-Lee graduates were among those who established the Asheville Student Committee on Racial Equality (ASCORE) in the wake of the sit-ins at a Woolworth in Greensboro. ASCORE member Oralene Simmons, class of 1961, participated in Civil Rights Era protests and helped desegregate a public library in 1961. She founded the Martin Luther King Jr. Association of Asheville and Buncombe County in 2003. The group organizes local events each January to celebrate King’s birthday. Simmons credits the faculty at Stephens-Lee with inspiring her and other students to be leaders.

“The teachers that we had, they were our role models,” she says. “They really cared. We were a small community, a segregated community where everybody knew everybody. The teachers knew your parents and could just call them on the phone and speak to them about what was going on with you so that you would not fall behind.”

Bowman recalls band director Lennon driving him and fellow musicians to a music festival at North Carolina A&T in Greensboro. “Many people didn’t have cars in those days,” he explains. “After the festival was over, he took us to a movie and then brought us back. I’ll be willing to bet that he did all of that at his own expense.”

Focus on education

The quality and educational achievements of the Stephens-Lee faculty have long been points of pride among the school’s alumni. Beginning in 2017, Zoe Rhine, then a special collections librarian at Pack Memorial Library’s North Carolina Room, and fellow researcher Joe Newman helped quantify those achievements through a two-year research project focused on the school’s 1964 faculty.

The study, released in 2019, found 20 of the school’s 34 faculty members that year had earned master’s degrees in education, a remarkable achievement for a Black school in the Jim Crow South.

“North Carolina did not want Black teachers going to the North Carolina schools for degrees,” Rhine says. “So they [state officials] paid to send them to other places like [Teachers College, Columbia University], and a lot of teachers got their degrees from there.” Columbia eventually created an outreach program to bring summer courses directly to Asheville.

“A lot of the alumni I have interviewed said that their parents wanted them to grow up to either be a teacher or a preacher,” Rhine says. “It really came across loud and clear that all the local Black community highly, highly valued education because they knew that was the only way their kids could get out of poverty.”

And while no one is pining for the days of segregation, many say there were benefits to having students attend a school where the other students and the teachers looked like them and were part of the same community.

“They instilled a lot of dignity and pride in us, and I think that is something that students didn’t find after integration,” Simmons says. “They did not have that rapport with the teachers.”

Ongoing legacy

The experience of Stephens-Lee may even provide a model for Asheville City Schools (ACS) as it attempts to bridge the achievement gap between white and Black students. The district earned a worst-in-the-state designation in 2017.

PEAK Academy, a public charter school that opened in 2021 in West Asheville, has a majority-Black student body. PEAK’s executive director, Kidada Wynn, says the mostly Black staff and faculty have begun to close the achievement gap by creating a space where Black students feel accepted, respected and loved.

The school started with kindergarten through third grade and added fourth and fifth grades this past school year. It will add at least one grade per year up to eighth grade.

The community center’s Redmond recalls having only one Black teacher during her time at T.C. Roberson. She thinks PEAK Academy’s approach can be valuable for young students who may have little experience outside the Black community before entering school.

“Somewhere, we lost that drive for academics,” says Redmond, who worked for ACS for 11 years. “Maybe it was during the demolition of the high school or just [students] being triggered and having to deal with civil rights issues at Lee Edwards or Asheville High [in the late 1960s]. But maybe something like PEAK Academy can help bring that back.”

The Asheville school district’s population of Black students was 17.9% last school year, not large enough to attempt a PEAK Academy approach in any of its schools, says Redmond. But she thinks the district can play a role in preserving the memory of The Castle on the Hill.

“Stephens-Lee High School should be in the history lessons for the elementary, middle and high school levels,” she says. “When you look back at history, you aren’t always aware of the academic achievements of Blacks in this country. People should learn about this school, which was a hub of academics and athletics, and all kinds of extracurricular activities, for all Western North Carolina Blacks.”

My father , James E Penley , was made principle of Stephens-Lee right before the schools were integrated. As far as I know , he was the first and only white principal of the school. Why they did this is unknown but it is part of the school’s history. He then was made principal of the South French Broad Middle School after Stephens-Lee. To his credit , my father was not a racist white person and this I know for a fact since I was living with him and my mother [ taught at Hall Fletcher ] and really only heard him say good things about the Teachers and Students at Stephens-Lee and he was a big supporter of the sports teams and attended all their games. After the riot at Asheville High we were getting threats from racist whites in West Asheville because they felt he helped the transition from Segregation to Integration and for a few days the APD had a patrol car parked outside our house. My dad was also a Marine Veteran of the Korean War , grew up in a poor family in Asheville , and was Asst. Superintendent of Asheville City Schools when he retired. I was the co-captain of the first Asheville High football team with John Dusenbury in 1969 and feel that our family played a positive role in the transition of Asheville City Schools. John Penley