BY JOE ELLIOTT

“Odd things happen in a battle, and the human heart has strange and gruesome depths and the human brain still stranger shallows.”

― Nathaniel Philbrick, The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The state historical marker outside the well-appointed two-story home on Rutherford Road in Marion states it is the former residence of Daniel A. Kanipe, who, according to the inscription, “survived the Battle of Little Bighorn, 1876. A soldier in the 7th U.S. cavalry, he (Kanipe) witnessed defeat of Geo. A Custer.”

As a member of Custer’s cavalry, Daniel Kanipe, a native of McDowell County, was part of a military force tasked with helping pacify the Sioux (Lakota) and other native tribes in the Dakota and Montana territories at a time in the 1870s when that region was seeing a rapid influx of white settlers, including those lured there by the promise of finding gold in the Black Hills of present-day western South Dakota, a land many native peoples have long held sacred and regard as their ancestral home. The Battle of the Little Bighorn, also known as the Battle of Greasy Grass, was in large part the violent culmination of long-simmering tensions among the Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho toward this growing white presence and the threat it posed to the native way of life.

In June 1876, as the rest of the country was busy celebrating the nation’s 100th birthday, Custer and his troops reached a large Indian encampment bordering the Little Bighorn River in present-day Montana. Badly underestimating the strength and size of the forces amassed against him that day, Custer, who it must be said never lacked audacity in battle, decided to launch a frontal assault against the camp. Employing a strategy that had worked for him many times as a celebrated Civil War cavalry leader, he sent one battalion around the flank of the camp and placed another one in reserve, while leading the center himself. Unlike Chickahominy and Gettysburg, however, the results in this instance were nothing less than disastrous.

Nearly all of the 7th Cavalry was wiped out during the bloody battle, one made famous in print and later film as the site of “Custer’s Last Stand.” The Marion marker states that Kanipe witnessed Custer’s defeat, but, in fact, he wasn’t present at the time of the battle. Instead, he had departed a short time before to relay an urgent message from Custer and his brother, Capt. Thomas Custer, to Capt. Thomas McDougall and battalion reserve commander Capt. Frederick Benteen.

The order, according to Kanipe, was for McDougall to bring up his badly needed pack train of supplies without delay and for Benteen to bring forward his troops as quickly as possible. According to Custer historian Robert Utley, “As Kanipe turned aside, Custer signaled the advance (of his battalion). Some of the horses became excited and broke into a gallop, out in front of even Custer. ‘Boys, hold your horses,’ Kanipe heard Custer shout. ‘There are plenty of them (natives) down there for all of us.’” Kanipe then rode off to fulfill his last-minute assignment. As it turned out, this was the only thing that saved the young sergeant from likely being numbered among the hundreds of dead and mutilated soldiers found on the battlefield the next day. At least that’s how the story has always been told.

After his active military service ended, Kanipe moved back to Marion with his family (he married a widow of one of the soldiers killed at Little Bighorn). In the early 1900s, he became an employee of the U.S. Revenue Service, a position he held for many years, and during World War I served as captain in the 19th North Carolina Militia Home Guards. An outgoing man, Kanipe served in various civic and community roles in Marion, including as the longtime treasurer of the local chapter of the Masonic lodge. For the rest of his life, Daniel Kanipe held a special and unique position as one of the last living links to one of the most storied, if controversial, chapters in American history.

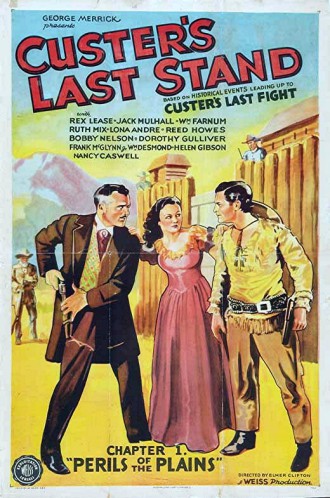

Journalists and writers everywhere sought him out, eager as they were for firsthand accounts of Custer and the battle, both of which had assumed mythic proportions by the turn of the century. (In 1912, when Kanipe was 59, the movie “Custer’s Last Stand” was released, the first of countless such film depictions to follow in the coming years.)

Daniel Kanipe died in 1926 and was buried with full military honors in Oak Grove Cemetery, just a short distance from his home on Rutherford Road. His story of heroic survival went largely unchallenged through the years until, that is, 2011 when writer Arthur C. Unger published “Custer’s First Messenger: Debunking the Story of Sergeant Daniel A. Kanipe.” In it, Unger, an amateur historian and Custer aficionado, calls into serious question Kanipe’s claims that he left the 7th that momentous day in order to deliver a critically important message from his commander. Instead, Unger argues, Kanipe left not to deliver a message, but to avoid danger. In other words, he skedaddled and ran, shirking his soldierly duties to save his own skin and scalp.

These are pretty serious charges, to be sure. However, Unger backs up his case with a close, detailed analysis of both the battle and Kanipe himself. Wishing to get some informed input on Unger’s inflammatory claims, I went in search of the best Custer/Little Bighorn experts I could find. I was helped out immeasurably in my search by Lee and Michele Noyes, editors of the respected “Custer Battlefield Historical and Museum Association Battle Dispatch.” The Noyeses put me in touch with several noted Custer experts, among them John Koster, the author of numerous scholarly works on Custer, including the book “Custer Survivor: The End of a Myth, the Beginning of a Legend.”

Koster told me that, for him, “the idea that he (Kanipe) was a coward or an outright liar seems to be to be incompatible with the man’s essential decency. He married Sergeant Bobo’s widow (Bobo was among those killed in the battle), raised the sergeant’s children along with their own, and was widely respected where he lived,” he said. “My only issue with Kanipe is that, when he was in his 70s, he inflated the number of dead Indians at the Little Bighorn.”

Frederic C. Wagner, author of “The Strategy of Defeat at the Little Bighorn: A Military and Timing Analysis of the Battle,” responded by saying that he disagreed with Koster’s assessment.

“Kanipe’s post-battle character and the way he led his life in later years has no bearing on what could have been a momentary case of cold feet,” Wagner told me. “To me, there are entirely too many issues regarding Kanipe’s story, and if anyone took the time to work on the timing of Kanipe’s journey, fit it into a similar study of Benteen’s move down Reno Creek and stirred in the Boston Custer and Giovanni Martini episodes — all of which I have done in my work — red flags pop up all over the place. Kanipe’s story of carrying a message is not a lot different than his bogus tale of seeing a hundred Indians sitting atop Reno Hill.”

Wayne Sarf, a noted Custer scholar and professor of history at Hunter College, takes a somewhat more charitable view of Kanipe. “The new theory seems to be that Daniel Kanipe loudly pretended to have brought a message from Custer to cover up the fact that he had simply dropped out of Custer’s command and hastened to join another of the 7th’s detachments,” Sarf told me.

“One problem with this approach is that Kanipe’s deception, if it was that, could only be foolproof if Custer, along with others, was no longer around to contradict him. How could Kanipe be sure that this would be the case? Wouldn’t it have been a better strategy simply to claim that his horse had given out, or bolted, something like that? Nobody could have predicted confidently that Custer’s command would be not only defeated but annihilated as well.

“Moreover,” Sarf continues, “there were a number of men from Custer’s doomed companies who ended up with the pack train though they perhaps should have properly been with their companies when Custer prepared to attack. One question that puzzles me is: Would a trooper faced with going into battle as part of a fairly powerful force of cavalry tend to conclude that he stood a better chance by riding off alone through hostile Indian country in the hope of linking up with another detachment that was not engaged? Remember that (Private John) Martin’s horse was actually wounded as he brought another message to Benteen, and he had to search a bit to find him. Dangerous work. I think it might be too early to simply write Kanipe off as a bogus messenger.”

Finally there is this from independent researcher Tim Bradshaw. “I have thoroughly researched every available piece of material that I could find on Kanipe, including public records in the courthouse in Marion,” Bradshaw told me. “I went through his pension files with a fine-tooth comb. Your question just can’t be answered conclusively. There are those who have completely made up their minds that the accusations against Kanipe are true. I have to admit there are a lot of things about Kanipe that are peculiar, such as the idea of a sergeant being dispatched to carry a message to the rear, when Custer needed all of the experienced soldiers he had on the line to fight with him.

“On the other hand, there are many positive aspects of Kanipe’s career following the battle. As far as his interviews go, as he was aging, there is no doubt he suffered from some memory loss. I am sure Unger’s book is a shock to any of the descendants of Kanipe,” Bradshaw continued. “However, he has done a meticulous job in comparing notes of Kanipe’s statements alongside those of other soldiers’ statements. I was aware that some people already felt this way about Kanipe, and I will have to admit, it was not, as a fellow Tar Heel, something that I really wanted to learn about him.”

So was Daniel Kanipe in fact a fraud, or, short of this, did he inflate or willfully misremember his own role in the Battle of the Little Bighorn? Or was he, instead, just what he claimed to be, a young soldier simply trying to do his best to fulfill his appointed duties on that terrible day amid the chaos and fog of war?

Like Custer himself, Kanipe’s story now seems forever mired in controversy and conjecture. However, for Terry Johnson, a 7th Calvary re-enactor from Iowa who role-plays Kanipe in battle, one thing is certain. “Sergeant Kanipe’s account of the battle was the most widely accepted and used for accuracy,” he told me. “He served honorably and did his duty.”

Footnote: In yet another controversial twist of the story involving the Tar Heel sergeant, Kanipe was charged with helping identify the bodies of his fallen comrades in the immediate aftermath of the battle. Among the dead Kanipe identified on the field was a Sgt. August Finckle. However, many years later a man named Frank Finkel (1854-1930) would make bold claims of being this very August Finckle, thus making him the sole survivor of the fight. Many such claims were put forth in the years following the historical battle, most of them easily discredited. However, the Finkel story is one that has over the years gained purchase with a number of historians, including Koster, who now accepts it as largely authentic.

Joe Elliott is a writer and educator who lives in Asheville.

Cool article- well written and informationy. More of this stuff please ( local history).

I’m not sure ‘pacify’ is the right term to use for what Custer was trying to do, but hey I’m sure most history textbooks published in Texas would agree.

Also, I wonder if 7th Cavalry re-enactors of Custer’s of The Battle of Little Bighorn stick to the true story of the battle by losing? I’ve often wondered the same thing about Civil War re-enactors too.

Yes, boatrocker, they do. Indians looting the bodies after the battle is a big part–a friend told me they were thinking of getting a bunch of cheap toy rifles and hats to stash on the far side of the river for “looting,” so they wouldn’t have to go to the trouble of returning expensive gear to its rightful owners after the event. And as a Confederate re-enactor, I have been defeated at Pickett’s Charge twice. The small re-enactments I do in California are not actually depicting real battles, though they may carry the names of real ones, so generally the Confederates win the first battle and the Yankees win the second–just like the actual Civil War.

Express Contributor(not enough guts to even put your name on the article),

You did take the time tested method of gaining popularity by printing lies (too many to mention) to an audience that doesn’t know any better. Major historians would disagree with scores of points you make including Donovan, Sklenar, Gray, utley, Scott and Fox. The Battle of the Little Bighorn has so many interesting aspects and what ifs it’s always sad to read someone without the scholarship and integrity needed to write one. It’s because of people like you that the US Government coverup could take place and still be going on.

Hi Scott,

The author’s name is listed at the top of the article. When folks contribute only one or two articles to Xpress, they don’t always create a user account on our site.

Thanks for reading,

Virginia

Does the author of this article know his name is so similar to that of Major Joel Elliott, who died at the Washita battle?

I was wondering the same thing!

I wrote a great deal about Kanipe in several articles and books. The “experts” noted above left out the most important detail. Late in life McDougall write Kanipe a recommendation and vouched for him being a messenger.

Folks,

Mr. Donahue is the leading expert on the Little Bighorn battle. On a side note, the article, which is written in a manner that does not follow a proper contextual setting, shows that the author has little or no knowledge about how a frontier cavalry unit functioned in the Plains Indians War.