Updated at 5:50 p.m. on Sept. 18: Results from the Reimagining Public Safety discussions were made available through the city’s public engagement website the afternoon of Sept. 18. Currently posted are the consultant’s narrative report, the consultant’s summary report and responses to open-ended questions from the city’s online questionnaire. Responses to multiple choice questions are “being analyzed for discrepancies” and are not expected to be posted until Friday, Oct. 2.

The survey results are in, and city-facilitated conversations have (momentarily) paused. Asheville community members are now waiting to see how their concerns will influence city policies on public safety and policing.

City staff, in partnership with three independent facilitators, hosted five virtual listening sessions and an in-person drop-in event the week of Sept. 8 to learn how residents envision the delivery of public safety services. An online survey was posted to the city’s website; simultaneously, staff and facilitators worked to connect with impacted populations unable to access the online sessions.

Looming in the background of these efforts is a firm and quickly approaching deadline. Asheville City Council must vote on budget allocations for the remainder of the fiscal year on Tuesday, Sept. 22, leaving little time to synthesize and consider participants’ input. In late July, Council approved a budget with only three months of funding for city departments; failure to reach an agreement on the remaining budget could lead to a government shutdown.

City Manager Debra Campbell has publicly stated she will not support activists’ demands to immediately cut funding to the Asheville Police Department by half and reinvest that money into social services. As shared in a prerecorded video message played at the start of each public engagement session, she instead will “recommend some budget adjustments if necessary as a result of these conversations.”

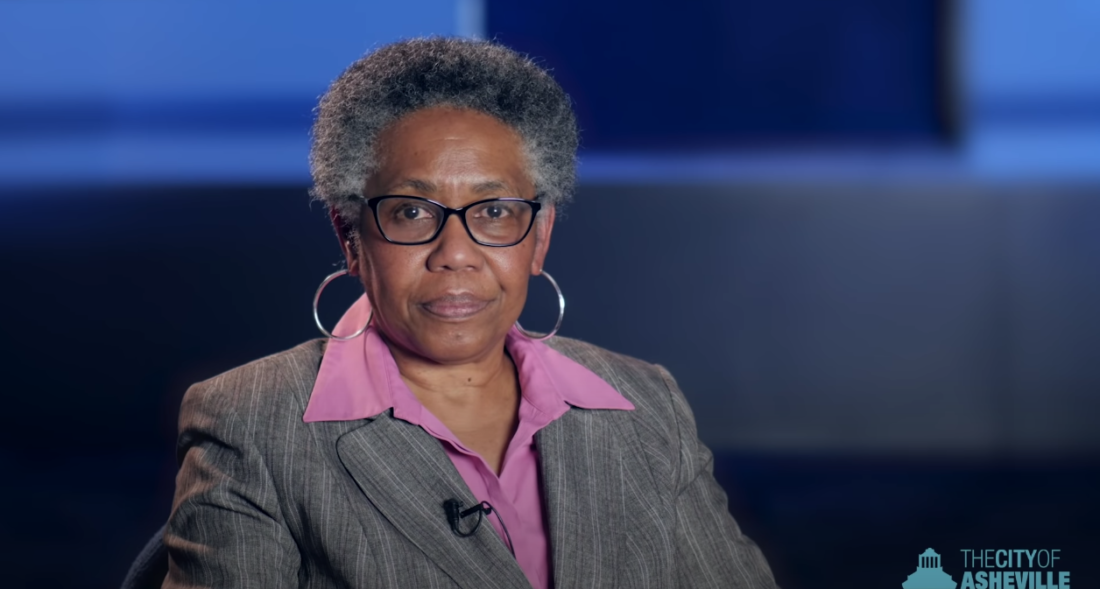

Shemekka Ebony Coleman of #IAmBrilliant and Christine Edwards and Glenn Thomas of Amplify Charlotte were selected to facilitate the community discussions; facilitation costs were not to exceed $10,000. After the engagement process concluded, the consultant team submitted a summary report of the listening sessions and survey responses to city staff.

As of press time, the city had not provided Xpress with a copy of the report. Recordings of the listening sessions previously available on Amplify Charlotte’s YouTube channel were taken down at some point between Sept. 12 and Sept. 14.

All documents related to the public engagement process will undergo review by the city’s legal department, city spokesperson Polly McDaniel said in an email exchange with Xpress. The summary report on the listening sessions, as well as survey results, will be posted by noon on Friday, McDaniel said.

Because the listening session recordings were made by private consultants, they would not be considered public records unless they were shared directly with city officials, says media attorney Amanda Martin, who represents the N.C. Press Association.

Legal requirements

Under state law, the APD is required to enforce city ordinances, serve arrest warrants and investigate things like traffic accidents, violent crimes and property crimes, Campbell explained in the introductory video for each public engagement session. Currently, 51% of the APD budget goes to patrol functions, 19% to criminal investigations and 30% to administration, finance and special services Based on the $30 million APD allocation proposed in Campbell’s first 2020-21 operating budget, those categories would get $15.3 million, $5.7 million and $9 million, respectively.

Facilitators encouraged listening session participants to think within those general parameters as the residents provided feedback on what safety should look like in Asheville. Xpress listened to two of the six public engagement sessions, one held Tuesday, Sept. 8, and one on Thursday, Sept. 10. The discussions centered around three questions derived from topics explored in the online survey.

“What makes you feel safe?”

Safety happens when everyone in the community is treated equally, an attendee shared at the beginning of the first listening session. Others soon chimed in: When neighbors share similar values, know their peers can meet basic needs like food and shelter and don’t feel threatened by police interactions, they said, they reach a sense of security.

One attendee, who identified as a Black man, told the group he felt safe when he felt like he was represented. In Asheville, a city that is approximately 83% white, he explained that he often feels uneasy and targeted.

A different caller cited transparency as a major concern. If more information about police funding and how officers respond to calls were available to the public, the commenter said, residents would feel more comfortable.

But safety is a broad term that means different things to different people, said Victoria Estes, a local resident who attended a listening session and the in-person feedback session. “It’s a sliding scale,” she told Xpress in an email sent after the engagement process. “I usually feel safe, but in instances like the nights of the protests where my roommates’ skull got cracked open by police and I was shot and pepperballed, no, I did not feel safe.”

“What does the APD do? What areas should be a priority, and which should be reallocated?”

Participants were shown a list of the APD’s specific duties, including drug and alcohol enforcement, property crimes, nuisance crimes and responses to individuals experiencing addiction and mental health crises.

Several attendees emphasized that mental health services should be provided by outside groups trained to assist in those situations. Others suggested reallocating funding to existing nonprofit organizations, such as BeLoved Asheville and SeekHealing, that provide support to individuals with addiction and people without housing.

Reimagining public safety goes hand in hand with reimagining public health services, an attendee added. Public health must also be considered when discussing mental health, addiction and domestic violence, others said.

Jean Parks, a Buncombe County resident who visits Asheville often, attended the listening session on Sept. 9. She expressed disappointment with the questions asked, criticizing their focus on the functions of police and their degree of involvement.

“There was very little discussion on how the police should carry out their duties,” Parks told Xpress in an email. She said police must become aware of their personal biases, respect every person and de-escalate situations whenever possible.

“Who is missing from the conversation?”

The virtual listening sessions excluded anyone without internet access or a computer from participating, several attendees noted, when asked to brainstorm about community members absent from the discussions. All but two of the sessions were held during the day, creating a barrier for anyone who works at that time, others added.

Noting the lack of publicly available data about who was taking part in the conversation, one participant said it was hard to tell who might be missing.

City officials identified groups including “Black, Indigenous and people of color; people without housing; people who suffer from addiction; people who live in public housing; and people who have mental illness” as most impacted by policing disparities, according to Asheville’s Reimagining Public Safety website.

What comes next?

At Council’s meeting of Sept. 22, Campbell is expected to present the report’s findings in conjunction with a new budget proposal. Public comment on the budget amendment will be held immediately after that presentation, followed by Council’s official vote.

The budget allocation is just the beginning of the public safety discussion, Campbell reiterated in her prerecorded remarks. Community conversations will resume in November as staff begin crafting budget recommendations for the 2021-22 fiscal cycle; Council also hopes to engage with members of the public to hear stories from the local racial justice protests that followed the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in late May.

“As we move forward with redefining roles and responsibilities of police and other city departments and our relationships with community partners, we want to move as fast as we can without leaving anyone behind,” Campbell said.

Close working partnerships between the police and social services agencies trained to deal with domestic disputes, mental health and drug issues, etc.,, which seem to be the source of difficulties when police along are called, would appear, to a lay person, a sensible step. Have these kinds of partnerships been tried in other cities? What do the professionals in these areas say? Were they surveyed? Has what used to be called “community policing” been tried in Asheville? Is this no longer a valid concept among policing experts?