When an amateur urbanist trained his video lens on downtown Asheville this spring, he found the city’s core to be surprisingly empty. Of buildings, that is.

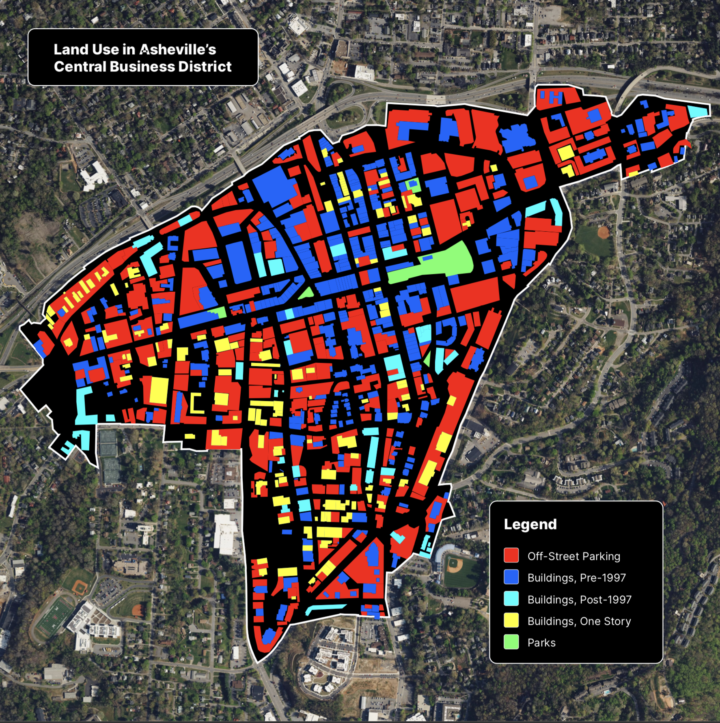

According to Rob Robinson, 57% of buildable surface area in the Central Business District, not including parks or streets, is surface-level parking lots. That doesn’t include parking garages or on-street parking.

That, he argues in the popular video titled “Why my city is mostly empty” is wasted space in a city with a housing crisis, and a result of bad land use policy.

“Land use policies have a cost that leads to bad land use downtown like this parking lot,” Robinson says in the video, standing in an empty lot on Coxe Avenue.

Those costs include a less walkable, more dangerous area for pedestrians, including Asheville’s 12.5 million visitors a year. Because of that, downtown is less desirable for developers, Robinson argues.

Indeed, Asheville’s percentage of surface parking in its Central Business District doubles that of other, larger urban cores, according to parkingreform.org. Of the 100 major U.S. cities surveyed, only two — San Bernardino and San Juan, Calif. — surpass 40% surface parking in its “central city.” Closer to home, cities like Raleigh, Atlanta, Charlotte and Charleston, S.C., have somewhere around 25% surface parking in their urban cores.

Robinson and a couple of members of the city’s Planning and Zoning Board say the parking surplus is due to regulations in the city’s Unified Development Ordinance (UDO) that make it too difficult to build downtown.

City of Asheville Planning and Urban Design director Stephanie Monson Dahl doesn’t dispute the issues with surface parking.

“We have too much,” she acknowledges. But she disputes that the excess of empty lots is singularly the result of bad land use policy or that there is any one planning policy that could incentivize owners to develop lots that currently generate passive income through parking. In fact, she says, the prevalence of parking predates many of the city’s current land use policies.

The on-ramp

The parking debate in downtown Asheville goes back many decades.

In 1979, two banks purchased an entire block of historic buildings on Patton Avenue between Church Street and South Lexington Avenue to demolish them for surface parking lots, probably to provide parking for their employees and customers. Many were upset about the plan.

“Both the property owners and the [Asheville Revitalization Committee] are extremely shortsighted in this action … of the wholesale destruction of an entire block of Patton Avenue for a single-level parking lot. Any more missing teeth in our streetscape and downtown will end up looking like it needs dentures,” wrote Jim Samsel in an editorial that was published in both morning and evening newspapers on Jan. 1, 1980, according to Buncombe County Special Collections.

That block remains surface parking today.

This story is one of many that led Robinson, a 24-year-old former UNC Asheville student and freelance videographer graphic designer and musician, down a rabbit hole of research, which he calls a “precipitous descent into car-induced psychosis.” He started making videos about carcentric areas of Asheville — including the stretch of Patton Avenue near New Leicester Highway — and explaining in his unique style why the design makes no sense.

His videos have garnered a lot of attention on YouTube, one with more than 93,000 views as of July 1, and their success has led him to pivot his career toward urban design issues, including downtown’s parking surplus.

Now that the city is growing, Robinson and others argue that it’s vital to attract as much development to the city’s core as possible to limit urban sprawl. But they say downtown’s building gaps scare away potential developers because of the decreased walkability of surface parking lots. Of which there are many.

“There’s an abundance of surface parking lots, and I think the best thing that the city can do to try to put those lots back into productive use as a building instead of a surface parking lot, is to look at the barriers to development,” says Geoffrey Barton, chair of the city’s Planning and Zoning Commission and CEO of Mountain Housing Opportunities.

Overregulation?

Barton acknowledges that much of downtown was built before the city had a zoning ordinance. Now that times have changed, leaders are trying to figure out how to maintain downtown’s charm while promoting appropriate growth.

“We used to have many more vacant buildings and storefronts downtown. With the rebirth of economic activity downtown through the 1990s, you don’t see a lot of vacant ground-floor retail space anymore. We may be running out of inventory for ground-floor retail,” Barton suggests. Limited empty retail space and a plethora of undeveloped lots could read as an opportunity for property owners, but developers aren’t exactly lining up.

Jared Wheatley, a contractor who serves on the Planning and Zoning Commission, says the city’s Design Review Committee requirements are too onerous for smaller developers who don’t have the capital to build a massive complex or time to wade through months of red tape to get approval.

The Design Review Committee was created to ensure design standards are consistent and the city avoids getting, for example, a corporate drive-thru coffee shop in the middle of the South Slope. Review by the committee is mandatory in the Central Business District and certain areas along the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers within the city, according to the city’s website.

Requirements to install sidewalks, curbs and trees, and utility improvements are overly onerous burdens for smaller developers and should really be taken care of by the city, he argues.

Plus, Wheatley says it simply takes too long to get through the review process and incentivizes any development to move outside of those areas or the city altogether.

“My contention is that it impedes downtown development because it’s an extra step in the overall development pattern.”

However, Monson Dahl says she has heard from community members that they want staff — and by extension, City Council — to maintain some control over what types of development arise in those areas and that people wouldn’t be happy if something moved in that was counter to the architectural vision of the Central Business District in particular.

However, if that sentiment changes, staff would be glad to change the rules, she says, and is going through a process to tweak the design review guidelines now. Monson Dahl encourages interested parties to get involved.

Further, while many American cities require nonhotel developers to include a certain number of parking spots for each unit built, Asheville does not have that rule in its Central Business District. The Planning and Zoning Commission recently recommended eliminating them citywide, a change that’s likely to come before City Council in August, Barton says.

That puts Asheville on the front end of the national trend to eliminate those requirements in an effort to promote more walkable districts that are less autocentric, Monson Dahl says.

However, the lots downtown already exist, so the challenge is to incentivize developers to build on lots that are generating income via parking for business owners with no additional investment. Then there’s the fact that many of downtown’s lots are owned by businesses in adjacent buildings that want to retain parking for their employees and customers, she says.

“The truth is that there is no incentive right now for people to develop that parking because of the local economics of building anything [profitable],” Monson Dahl acknowledges.

Single-story buildings

One rule in particular spurred Robinson to make his parking-related video: No new single-story buildings can be built downtown without an exception from City Council.

“A ban on single-story buildings downtown is aimed at the benefit of downtown density. So has this policy achieved the outcome that we’re looking for? No, not at all!” Robinson argues.

Plus, there’s a wide range of popular businesses that operate in single-story buildings downtown, he continues. From Green Sage Cafe to Asheville Pizza and Brewing Co. to most of the South Slope, the Central Business District is full of them.

“Should we really be completely banning one-story buildings and an effort to create density downtown, when our downtown is mostly empty space, mostly parking, and under the current rules, almost nothing gets built? I don’t think so. A ban on single-story buildings isn’t free. It doesn’t automatically create density, it doesn’t automatically add a second story to every building that would have been built one-story downtown. It just filters out those one-story uses from being able to exist here,” he says in the video.

In effect, Robinson points out, preventing single-story buildings lowers downtown’s density rather than increasing it, as intended. Barton and Wheatley echo that argument from their positions on the Planning Board.

But Monson Dahl says it’s not that simple. She doubts that making it easier to build single-story buildings as opposed to two-story buildings would immediately make potential developers more interested in the Central Business District because every project needs to be financially viable.

Smaller buildings bring less opportunity for revenue, and considering the cost of land, labor and materials in Western North Carolina right now, she doesn’t think there are many projects that could afford building just a one-story building. If a building is taller, it still only needs one foundation, which is the most expensive component, she points out.

The rule was added to the UDO 15 years ago during a time of rapid growth when the city was concerned with encouraging as much density as possible.

“There was a thought that … we really needed to infill to be able to support all the people that are moving here. [People thought] there needed to be a potential signal in our ordinances about what is appropriate for downtown,” she says.

Nowadays, she’s just not hearing many developers or owners of lots complaining about that rule, she says.

Regardless, like design review guidelines, if the mood of the development community has shifted around whether the city should allow single-story development downtown, she would love to hear that argument, and staff will incorporate those wishes into upcoming discussions around tweaks to the UDO.

“If that’s what people want now, let’s do it. Engage in the process,” Monson Dahl says.

Circling the lot

Ultimately, Monson Dahl acknowledges that the city has more work to do to update its ordinances and guidelines.

“I think that the process can be streamlined and be made more attractive for people looking to do the kind of development that we want to do here,” she says.

Plus, Asheville’s housing shortage is well documented, and planning staff has that top of mind when proposing tweaks to the vision for planning and zoning.

“We’re trying to increase the amount of housing, the variety of housing, opportunities for housing, specifically in downtown and on [public] transportation corridors,” she says.

Indeed, those efforts are being noticed by folks like Robinson, who acknowledges that things seem to be heading in a positive direction now.

Monson Dahl reiterates over and over that she hopes the community will continue to engage with the process at committee meetings and with staff to ensure the city moves in a direction that everyone feels is positive.

For his part, Robinson plans to keep his camera on to bring as much attention as possible to land use issues in Asheville — one YouTube video at a time.

Monson Dahl’s responses would be funny if they weren’t so sad

Of course this kid is right. Asheville wants to be walkable but refuses density, hates traffic but designs everything around cars.

Get the city out of its own way. Upzone, abolish parking minimums, and make building a right. And watch downtown become what it always should have been

Robinson supported a downzoning in the River Arts District. The City already doesn’t require parking downtown and within 1 mile of the CBD. Oftentimes when residential or commercial developers try to build downtown, the surrounding businesses protest it.

Asheville suffers DECADES of ignorant, naive elected democrackkk NON ‘leaders’, who have succeeded in ruining the city at this point. We need a REAL LEADER in the Trump style to turn this place around ! WHY do elected democrackkks DESTROY cities, counties, states and countries ?

WHAT?! Over-regulation causes unintended problems?