In 1994, Asheville was just a weekend place that I escaped to from Greenville, S.C., with my then-husband, Blane Sherer. I thought it was just a getaway; I did not know I was looking for something, but I found it: poetry.

In our hotel room, I read in the Mountain Xpress that Nikki Giovanni would be featured at the Asheville Poetry Festival. Because I had just begun putting pen to paper, because her poem “Ego Trippin’,” a creation myth, spoke to me as a teen, I wanted to go hear her read, but I had a fibromyalgia flare-up while on our trip and was not able to attend. But I bookmarked the event somewhere in my psyche.

I had an uncanny sense of belonging amongst the Cherokee Mountains on that trip, so I asked Blane to see if he would call about a job opening at Memorial Mission Hospital. He got a position at the hospital a year later.

During that year, I discovered the Asheville Poetry Slam, run by Allan Wolf at the green door down Carolina Lane. I made many trips up the mountain to read and slam there. Bob Falls — the founder of Poetry Alive! — was at every poetry slam and asked me to work for Poetry Alive! I performed contemporary and classic poetry in schools across the country — three shows a day, five days a week. It was a performance-poetry training ground. Bob had also founded the Asheville Poetry Festival on the UNC Asheville campus. I later performed there. These literary spaces created by Bob Falls and Allan Wolf, my spiritual brothers, helped me to spread my poetic wings.

Our family moved to Kenilworth into a yellow Germanic Cape Cod in 1995. Our backyard edged a Confederate cemetery and was three blocks from a slave cemetery at Bethel “A” Baptist. My house was a way station for the many ancestors. When I first began my sojourn at the slave cemetery, it was abandoned and only on a few people’s radar. I have been writing about the ancestors there ever since. In one of my latest poems, “How the Dead Speak,” I write about them this way:

Arrows of black crows,

pointing

in a tongue so plain

I can’t mistake their singing.

I became a downtown literary and arts dweller. I frequented Malaprop’s Bookstore in its first incarnation, which acted as an oracle to me. Books seemed to drop off the shelves pointing me in the direction of my own spirituality and creativity. Later, I worked at Malaprop’s. I never brought home a paycheck because I had first pick of every book of interest. I became pocket poor, but book rich.

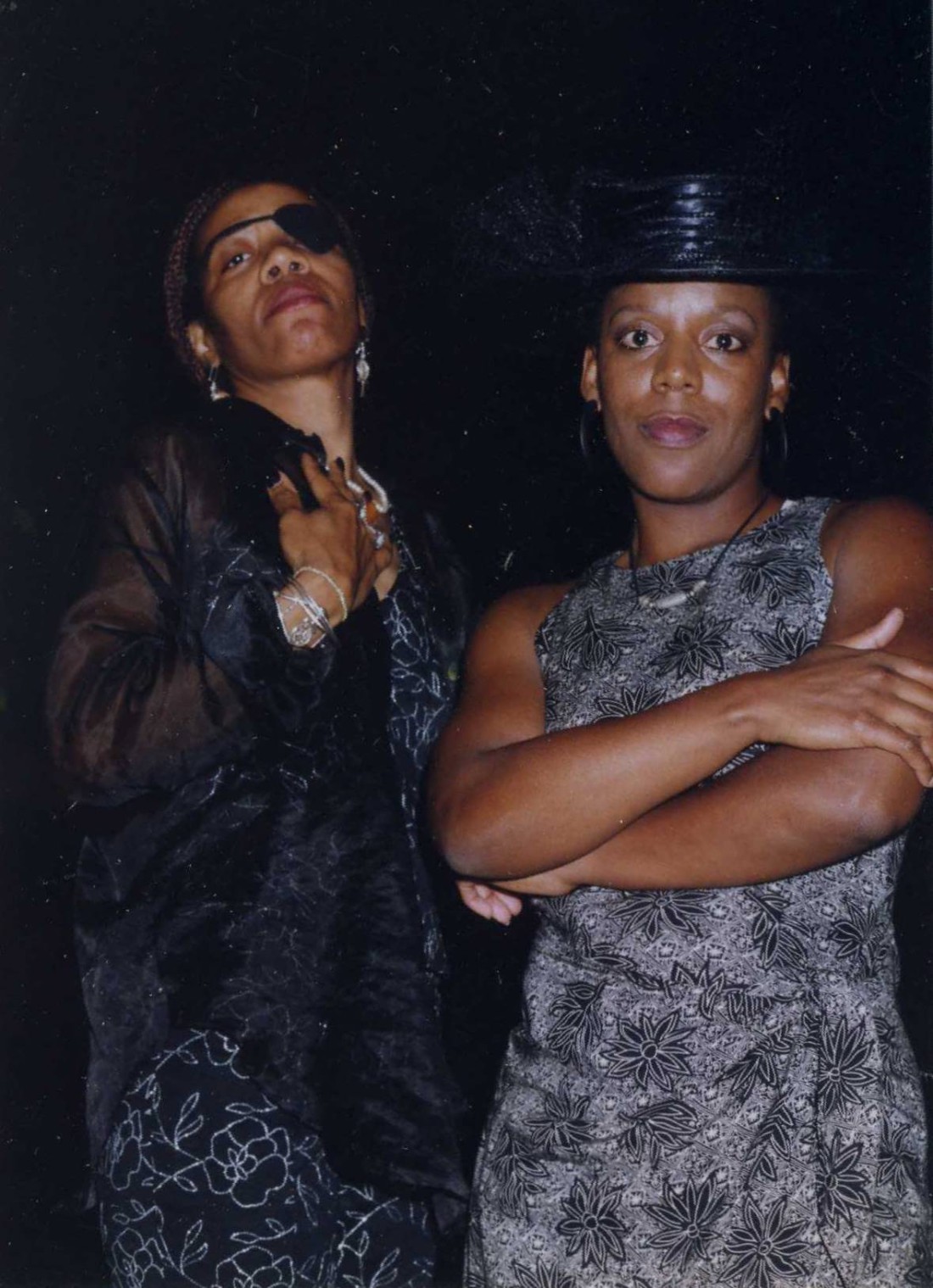

When the Ku Klux Klan marched in Asheville in 1997, concerned citizens of all faiths and races protested by holding a unity rally at the Reid Center. It was a powerful day of songs, speeches and dances. I did my poem “If I Ain’t African” down the aisle. The crowd gave me a standing ovation. Peggy Baldwin and John Loyd, booking agents for artists, were in attendance. They asked to sign me on to their artist touring roster. My poetic reach turned national that day.

As my poems are rooted in social justice, it was quite fitting that I was launched by responding poetically to a hate group amongst my tribe in Asheville. This is Asheville, the Asheville I remember, the town that gave me room to grow as a poet and as a person, a town that turned me into global citizen.

Glenis Redmond is the poet-in-residence at the Peace Center for the Performing Arts and the State Theatre in New Brunswick, N.J., and is senior mentor poet for the National Student Poets Program.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.