When people first learn of my involvement in restoring the Thomas Wolfe House, they generally ask two questions. The first one is, “Why in the heck has it taken so long?”

|

|

|

Photos courtesy Pack Memorial Library

and Thomas Wolfe Memorial |

|

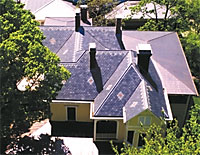

The Old Kentucky Home in the 1930s, and in 2004, following six years of museum-quality restoration

|

Some folks have dubbed it the “one-nail-a-day restoration,” and that is certainly understandable. I was involved in this extraordinary project for 26 months, and it’s been nearly six years since the July 24, 1998 fire that ravaged the historic home. But the N.C. Department of Cultural Resources’ decision to undertake a museum-quality restoration turned what might have been a far more straightforward proposition into an exacting and challenging labor of love. And the long-awaited end product is something the people of Asheville can be justly proud of.

The fire that erupted during that year’s Bele Chere, started by an unknown arsonist, destroyed significant portions of the Thomas Wolfe Memorial, a state historic site since the mid-’70s. But it would have been a lot worse if not for the Asheville Fire Department’s prompt and effective response. They were on site within one minute after the call came in. And while some fought the flames, others covered original Wolfe family furniture with wet blankets to protect it until the fire was contained. Even so, 25 percent of the house and 15 percent of the furnishings (200 items) were consumed. The most significant losses were in the dining room, where the fire began; they included all windows, wood flooring, doors and the original Wolfe family furniture and table settings.

As soon as the fire was out, Wolfe House staffers teamed up with qualified volunteers from the Carl Sandburg Home, Biltmore Estate and the National Park Service to tag and remove 600 artifacts and pieces of furniture, whose restoration took nearly six years. Even the best-preserved pieces required some degree of restoration and repair, and the last six weeks or so has seen a whirlwind of activity just getting it all back inside the house.

These dedicated volunteers were the first of some 400 people who came to be involved in restoring the Old Kentucky Home. The 29-room boarding house, where Thomas Wolfe spent significant portions of his childhood, was immortalized in his acclaimed 1929 novel, Look Homeward, Angel. The property remained in the family until 1948, when it was sold to the newly formed Thomas Wolfe Memorial Committee. The committee (and, later, the city) ran it as a museum until it was turned over to the state of North Carolina in 1975.

Sleuthing the past

The house at 48 Spruce St. was built in 1883 for E.M. Sluder, who moved here from Charleston to start the Asheville Bank. It was state-of-the-art construction, with beautiful windows, expensive trim and hardware, and all the accouterments a wealthy homeowner of the time would have expected. Sluder completed at least two major renovations (including expanding it from seven rooms to 18) before Julia Wolfe, Tom’s mother, bought the property in 1905 and converted it into a boarding house.

A decade later, Julia had saved enough money to move ahead with her own extensive plans for the house, and the end results reflect her frugal, no-nonsense approach. Her additions — the south-side sun porches and the northwest and southwest wings, all completed in 1916 — feature low-pitched roofs with metal shingles, which were significantly cheaper than trying to match the original slate roof. In four places, dividing walls were erected to create hallways to new areas or extra rooms. The plaster in the additions was the significantly rougher two-coat kind (another significant cost savings); in the divided rooms, the dividing wall is two-coat plaster while the others are the three-coat plaster used in the original house. When an addition enclosed a window, Julia moved it to a new location. And when new doors or windows were needed, Julia bought the cheapest ones she could find. Finally, much of the work was probably done in exchange for room and board by local men who knew their way around a barstool better than they knew their way around carpentry tools.

The great challenge of the Wolfe house restoration was to salvage and duplicate those frugal measures and sometimes shoddy workmanship. required examining each flaw (such as the unlevel rear-hall floor) or substandard piece of workmanship (such as a door bottom that had been radically trimmed to fit in an askew opening) to determine whether it stemmed from half-baked workmanship circa 1916 or merely from decades of neglect and normal wear.

A massive cover-up

|

|

|

|

Photos courtesy Thomas Wolfe Memorial

|

|

After the fire, a fitted blue tarp placed on the home’s roof was such a shocking shade of blue that airplane passengers flying over downtown could easily spot it. Restoring the roof to its current splendor involved scrutinizing pre-aerial photos with a magnifying glass, reviewing old tax records, researching the region of Pennsylvania where the original slate shingles came from — and installing them in the traditional manner.

|

But before we could even begin to address such complex issues, we had to tackle more pressing concerns. The heat and flames had compromised the entire roof and second floor ceiling, and a demolition contractor was hired to remove all framing, plaster and roofing materials from the second-floor ceiling up.

That immediately sparked a frantic round of discussions and brainstorming sessions (both here and in Raleigh) on how to cost-effectively protect what remained of the house until repairs could be conceived and carried out. Local civil engineer David Smith quickly designed a weblike framework supported by 6-by-6 posts running all the way down to solid ground in the basement. The whole thing was covered with a fitted rubber tarp — such a shocking shade of blue that I easily spotted it from the air as we approached the Asheville airport. This ingenious solution completely protected the opened top of the house during the ensuing five years; it was relatively easy to assemble (assuming you had a carpentry crew that thought nothing of running around on such a structure 60 feet off the ground), and it was relatively inexpensive (at least compared to such alternatives as a giant custom tent).

The next several years were spent trying to figure out precisely what needed to be done and who would do it.

Then, in November of 2001, Progressive Contracting Company Inc. got the contract to restore the historic structure to its 1916 condition. A few months later, PCCI awarded me the subcontract to complete all carpentry-related demolition and repair work on the project; soon after, I was hired as site superintendent instead.

When we first arrived on site, the structure had been under temporary roof for nearly four years. Even the rooms farthest from the fire had deteriorated due to smoke and water damage. In rooms adjacent to the epicenter, 115 years’ worth of layers of mostly lead paint had blistered wildly in the intense heat (which probably saved much of the woodwork).

Pieces of the puzzle

The Department of Cultural Resources’ central directive was to take all pains to salvage and use as much “historic fabric” (meaning anything original to the structure) as possible — even material that would later be covered by replacement plaster. This also required precisely duplicating lost parts and materials to match the originals in color, texture, size and type.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.