Asheville activist Steve Rasmussen has released a report critiquing the Downtown Master Plan draft, asserting that its enforcement powers on development issues are weak and that much control would be turned over to unelected boards to the benefit of developers.

The city will hold a public forum on the plan Thursday, Jan. 15, at 7 p.m. in the Asheville Civic Center banquet hall.

Rasmussen, known recently for his efforts opposing the controversial Parkside condominium project and the demolition of the Hayes & Hopson building in downtown, writes that the downtown plan “does contain some wonderful and visionary ideas for our future. But most of the teeth needed to enforce them have been pulled.”

According to his report, part of the problem was the process by which the plan was crafted.

“It happened just as the cynics predicted,” Rasmussen asserts. “Asheville’s Downtown Master Plan started out with great ideas for preserving a livable downtown as we grow, shaped over the summer by enthusiastic and thoughtful public input. Then it disappeared underground over the winter — and into the non-public meetings of a dozen or so members of an advisory committee dominated by developers and their advocates.”

The result, according to him, is that the plan “seems now to be degenerating into an undemocratic delegation of power into the hands of appointed, insulated boards that well-connected developers have plenty of experience in controlling.”

Mentioning that there were positives to the plan, he said his focus on the negatives is intentional.

“You probably won’t hear about the following problems unless we bring them up. And the questionable changes the plan recommends in the development-review process are likely to be adopted very quickly if we don’t speak out.”

Specifically, Rasmussen lays out six areas of concern: limits on building height; a drastic reduction in Asheville City Council’s power over development; compliance with some development guidelines remaining voluntary; a dismissal of local historic districts as a way to limit development; a dismissal of the importance of view corridors; and an unelected board (the Asheville Development District) that Rasmussen writes would “morph eventually into a mammoth centralized bureaucracy for buying and selling city land, development rights, etc.”

Of that last issue, Rasmussen states that “Asheville has experienced this sort of Soviet-style central planning before — in the 1960s and 70s, when autocratic City Manager Weldon Weir and his successors demolished large parts of the city’s downtown (including its African-American section at what’s now South Charlotte Street) in the name of urban renewal. We don’t need to delegate away what little power would remain with elected officials after the [Downtown Master Plan] strips City Council of its design-review function.”

The report advocates keeping Council’s powers over development intact and diversifying the planning board, among other measures — and rejecting the Downtown Master Plan if it keeps its current form.

The full report is below.

— David Forbes, staff writer

————————————————————————————————————

PROBLEMS IN THE DOWNTOWN MASTER PLAN DRAFT:

A CITIZEN REPORT

By Steve Rasmussen

Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2009

It happened just as the cynics predicted. Asheville’s Downtown Master Plan started out with great ideas for preserving a livable downtown as we grow, shaped over the summer by enthusiastic and thoughtful public input. Then it disappeared underground over the winter—and into the non-public meetings of a dozen or so members of an advisory committee dominated by developers and their advocates.

Sure enough, the draft plan that has re-emerged—just in time to be presented this Thursday evening to the public and City Council, who’ll be urged by committee members to adopt it whole, “without any tinkering”—is effectively gutted. Yes, it does contain some wonderful and visionary ideas for our future. But most of the teeth needed to enforce them have been pulled.

Participants in last summer’s meetings were told over and over by the Goody Clancy consultants that strong design requirements were the key to maintaining our downtown’s livable, human-scale quality of life; that if we had enforceable guidelines, we wouldn’t need the “political” City Council hearings that generate so much heat and rancor; and above all, that we don’t need to pander to developers, because our city is so desirable that we the citizenry can set a high bar for developers to meet.

It now appears that was mostly just high-gloss talk. Over and over again, the draft plan and the consultants’ responses to developer objections show “requirements” being diluted into “recommendations”; enforceability being sacrificed together with Council review; and a hasty retreat being beat from almost every proposed requirement developers considered too “restrictive.”

Here’s a summary of problems I’ve discovered in the DMP draft, followed by a more detailed discussion of each. I’m disseminating this report to a wide variety of people—preservationists, activists, officials, media, et al. (please forward at will!)—and we’re only being allowed one more shot at this, so I recommend you zero in on the particular problem or issue that matters most to you (whether one of the following, or one you’ve found on your own), attend the Thursday meeting (7 to 9 pm at the Civic Center), and vocally raise your pointed question or objection during the brief period the public will be given for comment. After the meeting, we’ll have three weeks to submit written comments to Goody Clancy, the consultants whom we’re paying $170,000 to create this plan. You may wish to CC your comments to City Council, who will be voting on the final plan March 10.

Please note: I’m intentionally focusing on the negatives here. There are a great many positive points in the draft plan, too—but you’ll hear all about those on Thursday. You probably won’t hear about the following problems unless we bring them up. And the questionable changes the plan recommends in the development-review process are likely to be adopted very quickly if we don’t speak out.

You can download a copy of the draft plan at www.ashevillenc.gov/downtownmasterplan. It’s in two parts, the Draft and the Appendix.

What you can’t download—because it wasn’t meant to be released to the public—is another document I’ll be citing: “Asheville Downtown Master Plan planning team response to Advisory Committee comments on Downtown Master Plan Preliminary Draft 2 dated 1 October 2008 In Draft Downtown Master Plan dated 2 January 2009.” Let’s call that “Planning Team Response” for short.

========================

SUMMARY OF PROBLEMS:

*1* HEIGHT RESTRICTIONS would be placed on new buildings in Asheville’s downtown core—except for certain favored developments, including Tony Fraga’s.

*2* Our cumbersome, controversial DEVELOPMENT-REVIEW PROCESS would be streamlined—but, at developers’ insistence, the power to approve large buildings would be mostly taken out of the hands of our elected City Council members and transferred to the non-elected Planning and Zoning board. Council’s role would be further reduced by eliminating the current Conditional Use Permit process.

*3* The “MANDATORY REVIEW, VOLUNTARY COMPLIANCE” design-review flaw—which has allowed developers of buildings such as Staples to get approval for one plan and then build a different one, and which was the impetus in the first place for the Downtown Commission to seek a new Downtown Master Plan—remains unchanged. Review would still be mandatory … and compliance would still be voluntary.

*4* The one mechanism that state law provides cities such as Asheville to enforce mandatory compliance—LOCAL HISTORIC DISTRICTS—is cursorily dismissed without any examination or analysis, apparently because developers feel it’s too restrictive. Instead, preservation of our historic downtown buildings would be, not enforced, but merely encouraged—largely by selling off the buildings’ “air rights” to new developments next door.

*5* Remember how eloquent the Goody Clancy planners waxed last summer about requiring tall buildings to be slender instead of massive so they wouldn’t CAST SHADOWS on nearby neighbors and streets? Remember their inspiring proposals and maps about mandating preservation of the VIEW CORRIDORS to the mountains that help make downtown Asheville such a pleasant place to live? All that is now tossed out the window as “unnecessary restriction.”

*6* In the long term, development decisions for city-owned land would be delegated to a non-elected entity, the ADD (ASHEVILLE DOWNTOWN DISTRICT), that would start innocuously small by handling matters like graffiti cleanup and marketing downtown. But it’s intended to morph eventually into a mammoth centralized bureaucracy for buying and selling city land, development rights, etc.

========================

DISCUSSION OF PROBLEMS:

————————————

*1* HEIGHT RESTRICTIONS:

The maximum height allowable would be “265 feet (27 stories)… (similar to the Ellington and Battery Park proposals)” (DMP Draft, p.56). Mostly this height would be allowed only in the lower-elevation areas that citizens generally agreed were appropriate for tall buildings, along with some “gateway” areas such as the Patton Ave. entrance to downtown. The downtown core would be limited to 145 feet (15 stories), “the intermediate height threshold defined by the community’s favorite 1920s structures: the Jackson, Battery Park Hotel, County building and City Hall.” (ibid.)

So far, that looks very much like what the community told the planners it wanted last summer—keep the big skyscrapers out of our downtown center, and put them on the South Slope and other less sensitive areas.

But wait—what’s this in the Appendix?

“Building height and density:

“[A] Substantial height and density are a traditional

hallmark of downtown streets and should

continue to be encouraged to support property

value, intensity of activity and urban design

character.

“[B] The intermediate 145’ height threshold applies

to much of the district to reinforce the

prevailing scale of tall traditional buildings like

the Jackson Building, and to reduce shadow

impacts on narrow streets.

“[C] The taller 265’ height threshold applies to

Battery Hill and previously redeveloped area

between Woodfin, and College, and Spruce,

to bring additional value and activity to these

areas and augment the skyline at high points

in downtown.”

(DMP Appendix, pg. S3-4)

“Substantial height and density” may be hallmarks in Atlanta or Boston—but the whole point of the big-building issue is that this is Asheville. This statement in the Appendix completely contradicts the Draft.

Why the exceptions for “Battery Hill” and the area between “Woodfin and College and Spruce”? A reference in the Draft, pg. 21, makes it clear that “Battery Hill” refers to Haywood Park—Tony Fraga’s giant skyscraper that City Council has rejected as way out of scale with the area. How did Fraga get special treatment from Goody-Clancy? Is this the “bad old way” of making special deals with powerful insiders?

This deference to a well-connected developer sets the tone for all the other problematic areas in the DMP.

As for Woodfin and College and Spruce, I’m not sure who’s planning what enormous building there—but it’s uncomfortably close to the County Courthouse and City Hall. Despite the ad-agency language about “additional value” and “augment[ing] the skyline,” allowing a Haywood Park-size building there would dwarf these signature downtown buildings and contradict the Draft’s claimed intent of preserving Asheville’s character.

————————————

*2* DEVELOPMENT-REVIEW PROCESS:

The UDO divides development proposals according to their size into Levels I, II and III. Levels I and II are currently subject to final approval by the Technical Review Committee, which is composed of city staff representatives. Level III—building projects of 100,000 square feet or larger—are subject to final approval by City Council.

No one likes this arrangement. The public doesn’t like the way TRC seems to rubber-stamp large, controversial buildings such as Parkside or Haywood Park, with TRC staffers claiming that their hands are tied by their narrow mandate to look only at their particular technical piece of the elephant—fire safety, traffic, etc. When the developer of Parkside, for example, saw that he was not going to win approval from City Council, he dropped just enough square footage from his design to shift it from Level III to Level II, and the TRC approved it.

Developers, on the other hand, don’t like having their proposals routinely OK’d all the way through the process till they get to City Council, where they can be scotched by a loud enough public outcry.

The subject reportedly raised a great deal of ire at the Advisory Committee meetings. One member, a co-founder of the local pro-business lobby CIBO, reportedly stomped around the room, proclaiming that he would only support City Council’s having final approval “if you can promise me no hippies, no artists, no activists, no mamas with babies on their hips will get up at City Council and stop developments” that are already approved at lower levels.

So Goody-Clancy’s plan considerably reduces the amount of say City Council will have. Although the DMP would have Council retain final approval for Level III proposals, the threshold for Level III would be raised considerably, from 100,000 to 175,000 square feet.

That means elected officials accountable to the public would have final say over far fewer proposals.

The much-expanded Level II would, under the plan, be subject to final approval by the Planning and Zoning board instead of TRC. Currently, P&Z is allowed to examine larger, non-technical issues such as building scale and appropriateness (indeed, it was the first body in the review process to fail to approve Parkside), but its rulings are only advisory to City Council. Under the DMP proposal, however, its authority would be enormously expanded.

But P&Z members are appointed, not elected—and therefore insulated from public accountability. Appointments to the 7-member P&Z board have always been the subject of intense lobbying of City Council by the development community. How much more intense will the lobbying become when P&Z is given final say over most large developments?

The DMP says nothing about the makeup of this much-more-powerful P&Z—the word is that won’t be discussed till just before the plan goes to City Council. I’m sure it’s safe to predict that the rationale for stocking the board with members of the development industry rather than representatives of the larger public will be the same it’s always been—developers have the “expertise” to judge projects by their fellow developers. Government watchdogs have another name for this classic rationale—the “revolving door,” or, “you scratch my back now, I’ll scratch yours when I’m on the board.”

In response to developer demands for eliminating City Council approval, the Goody Clancy consultants also noted in the PTR (ref. no. 9): “Limited use of the Conditional Use Permit process will also reduce city council role and permit more structured review process.” The new plan would make Level III approval subject to conditional-use permits only when conditional land uses actually apply—which at first seems sensible, but here is what this means: Currently, whenever a Level III proposal goes to City Council for final review, Council is required by the UDO to handle it as a “conditional use,” even if there are no actual special conditions involved. This compels Council to hold the review hearing as a “quasi-judicial hearing”—as if they were judges in a court case. Like judges, they are banned from receiving information about the proposal before the hearing. Council members complain that this process prevents them from learning any more about a proposal than they are told at the hearing.

But as bizarre as it may seem to hold conditional-use hearings when there are no conditional uses, this does have the political advantage of shielding City Council from lobbying by either side before the review hearing. Before we junk this peculiar way of doing things, shouldn’t we find out if there was a good reason for instituting it?

It may be that this process was instituted because it is the only legal way to deny approval of a project based on design standards—the Seven Conditional Use Standards outlined in the UDO, Sec. 7-16-2 part (c). Wouldn’t it have been wise for the consultants to investigate whether this or soemthing similar is the case before recommending its dismantling?

————————————

*3* MANDATORY REVIEW, VOLUNTARY COMPLIANCE:

At the Advisory Committee meeting I crashed last Monday morning, Downtown Commission chair Pat Whalen acknowledged that the draft plan still does not mandate compliance with design standards, which the Downtown Commission and the general public had insisted last summer should be a key element of any new plan. Instead, the plan would introduce what he called a “carrot and stick”: All Level II and Level III projects would be subject to design review by the Downtown Commission, as well as Planning and Zoining. If the DTC or P&Z denies approval, the developer could appeal to City Council.

I guess the “stick” here is the fear of those mamas with babies on their hips mobbing a City Council hearing. But that’s not exactly guaranteed to make someone like Staples, Inc. shake in their wingtips.

The plan would give developers the right to appeal a denial at any level in the process to the next level up (DMP Draft, pg. 71). It seems that it would be much more of a stick—and much more fair—if the appeals went both ways. A group of affected citizens should, conversely, be able to appeal an approval to the next level up.

The Draft makes a big deal about instituting public input at each step of the design-review process—without mentioning that the public already has the opportunity to comment at each step. The one innovation it does introduce is that developers of large projects would be required to meet and discuss their plans with the public before beginning the review process—which the UDO currently encourages but does not require.

The reason there is no mandatory compliance in the plan is because downtown developers object to *4*.

————————————

*4* LOCAL HISTORIC DISTRICTS:

At the last public meeting Goody Clancy held last summer, one of its consultants told me the draft would include a table showing a number of possible restructurings of the design-review process and their consequences. Included among these options would be the only one that would, under North Carolina law, allow for mandatory compliance: designating downtown as a Local Historic District, which would put final approval for design review in the hands of the Historic Resources Commission.

There is no such grid of options in this draft—only the flat recommendation of expanding P&Z’s authority, etc. as discussed in *2* above. Maybe $170,000 wasn’t enough to buy us an options grid.

And instead of an objective investigation of how an LHD might or might not be advantageous, it is treated like an afterthought and then summarily dismissed: “In addition, explore the pros and cons of designating a local historic district. (Note that local historic district designation could excessively restrict the ongoing investment that downtown needs to thrive by establishing stringent restoration standards without adequate financial support to help meet them.) (DMP Draft, page 30-31)

The last statement is the viewpoint that was presented to the Advisory Committee by a single historic-preservation consultant who is employed by a downtown-development company. It is not the view of most local or state preservationists, and it is certainly not supported by the well-known study conducted by Dr. Pamela Nickless of UNCA in 1997 on “Economic Development and Historic Preservation” (summarized at http://www.psabc.org/news/econ.htm). Nickless—whose study Goody Clancy was informed about, but apparently ignored—demonstrated the enormous jump in investment in the Montford district after it was designated a local historic district.

The DMP draft simply recycles many developers’ prejudices against local historic districts—which restrict them from demolishing historic buildings at will, and compel them to make historically appropriate alterations to their buildings instead of whatever suits their whims or costs the least—and marginalizes preservation by continuing to overlook the central role our historic buildings play in the character and desirability of downtown.

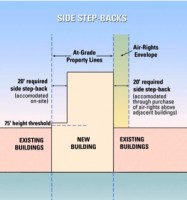

Worse, it encourages the development of massive buildings right next to historic properties by advocating the sale of the historic property’s “air rights” (DMP Draft, page 31). Developers could dodge the DMP’s proposed 20-foot side step-backs from adjacent buildings by buying the rights to the step-backs from the adjacent building’s owners—which would seem to defeat the DMP’s own stated purpose of requiring side step-backs, which is to minimize shadows and the depressing “slab” effect of overcrowded buildings.

Finally, it seems imbalanced, at least, for the plan to dismiss Local Historic Districts on the one hand, and on the other hand to advocate: “Diversify the Asheville-Buncombe Historic Resources

Commission to include Asheville Downtown Commission members, design professionals (including urban designers), sympathetic developers, construction professionals, and members with similar backgrounds.” (DMP Draft, page 32) What would be the point of this if the HRC is given no power to enforce downtown historic-design requirements?

————————————

*5* SHADOWS & VIEW CORRIDORS:

This may be the clearest example of how readily Goody Clancy backed off from its “livable” and “human-scale” design-requirement proposals when these met resistance from developers.

The problem of massive new buildings overshadowing smaller existing ones was in the forefront of public concern twice last year: The Coalition of Asheville Neighborhoods opposed the Horizons proposal’s large condo tower at the old Deal property on Merrimon Ave. because it would have cast the residential neighborhoods next to it in continual shadow, interfering (among other concerns) with residents’ solar-cell panels. And the Parkside condos would have cast a daily shadow over City Hall, as well as over City-County Plaza.

Preserving downtown residents’ and visitors’ views of the surrounding mountains from encroachment by massive buildings was also a frequently expressed concern. Again, Parkside highlighted this issue—one of the Pack Square Conservancy’s objections to the proposal was that it would block a traditionally admired view of the mountains from City-County Plaza.

The consultants told us we could prevent these problems by requiring tall buildings to be tapered, decreasing their mass as they rise (like the Jackson Building); by imposing restrictions on shadows; and by designating view corridors in which tall buildings would not be allowed.

Here’s what happened to those ideas in the back room. (It may be mere coincidence that the owner of the Horizons/Deal property, Chris Peterson, is also the most outspoken developer on the Advisory Committee.)

In the Planning Team Response document, the consultants answer an objection—perhaps from a non-developer on the committee—that “More height regulation [is] needed” (ref. no. 26):

“We did not feel additional height controls were necessary compared to previous drafts, and have in fact removed some regulations that we feel imposed unnecessary restriction:

“[A] Removed requirement that building floor length gradually decrease (by 2’ per floor) about 75’. This unnecessarily restricts upper floors; the 150’ maximum will still ensure reasonable building size; we did not want to force tapered building forms that would be out of place with traditional sheer vertical buildings in downtown.

[Which ‘sheer vertical buildings’ are those—the BB&T? The Wachovia??—S.R.]

“[B] Removed restrictions on new buildings casting shadows on private development parcels (restrictions on casting shadows on public parks remain). Further model study revealed that restricting shadows on private parcels dramatically crimps development envelope and forces tapered building forms out of character with downtown (precedent shadow ordinances we had invoked turned out to be geared to more suburban conditions). While removing these restrictions will impact private parcel access to direct sunlight, we feel this is a reasonable trade-off to maintain other important urban qualities and parcel value. Other sites out of downtown are better suited for solar power generation. The floorplate area and length restrictions and front step-backs that remain for taller buildings will help ensure that a reasonable amount of daylight and views remain among taller buildings.

[This strikes me as utterly arrogant, and contemptuous of the nearby residents whose access to sunlight would be “traded off” for “parcel value.”—S.R.]

“[C] New development is no longer restricted from designated public view corridors, but rather must provide photomontages illustrating how it would be compatible with important views. Curtailing development in view corridors would be overly restrictive, and lead to some very disproportionate impacts on certain parcels. Public review of clear before/after illustrations of the proposal will enable thoughtful accommodation of views and development through good architectural design and site planning.”

[If you allow a tall building to jut up into a view corridor, it’s hard to see how it will “thoughtfully accommodate” views for anyone except the residents of its penthouse.—S.R.]

————————————

*6* ADD (ASHEVILLE DOWNTOWN DISTRICT):

A good description of this is in David Forbes’ Jan. 6 article in the Mountain Xpress, “Asheville Downtown Master Plan draft lays out potential future,” at http://www.mountainx.com/news/2008/downtown_master_plan_draft.

Gordon Smith of Scrutiny Hooligans has aptly described this entity—in the form the plan envisions it eventually taking as an all-powerful, independent controller of downtown—as a “Petri dish for corruption.” Huge amounts of money and power would be controlled by appointed—not elected—officials who would be subject to no effective oversight.

Asheville has experienced this sort of Soviet-style central planning before—in the 1960s and 70s, when autocratic City Manager Weldon Weir and his successors demolished large parts of the city’s downtown (including its African-American section at what’s now South Charlotte Street) in the name of urban renewal. We don’t need to delegate away what little power would remain with elected officials after the DMP strips City Council of its design-review function (see *2*, above).

========================

CONCLUSION:

In sum, the Downtown Master Plan, which began with such a breath-of-fresh-air flourish of public input and citizen control over Asheville’s destiny, seems now to be degenerating into an undemocratic delegation of power into the hands of appointed, insulated boards that well-connected developers have plenty of experience in controlling. Although it is packed with excellent, far-sighted recommendations, these are made hollow by the plan’s weak requirements.

The public needs to resist the inevitable rush to implement the plan’s developer-friendly rule changes, and to avoid being swayed by arguments that “everyone has to compromise” and “we can’t delay any longer.” The fact is, Goody Clancy was right the first time—we DON’T have to compromise our quality-of-life standards to suit the demands of a few developers who want to continue putting up ugly, oversized cubes.

Historic preservation and renovation—not new development—has been the driving force behind downtown Asheville’s economic revival. This will prove even more true as the present recession deepens, since historic restoration is cheaper and greener and creates more local jobs than new development.

The organizers of the DMP process made one fundamental mistake in closing off the process to the public and moving it to a developer-dominated back room. They made another in repeatedly failing to provide a due proportion of seats at the table for the historic-preservation community.

It’s not too late to reverse these mistakes. The DMP is still only a draft. The planners could:

* Make a concerted effort with preservationists to research and discuss Local Historic Districts, the one tool that can give us “mandatory review, mandatory compliance.”

* Retain City Council review for all Level III projects over the old threshold, 100,000 feet.

* Investigate the consequences of dropping the Conditional Use Permit process.

* Consider how to diversify the membership of the Planning and Zoning board beyond the developer community, and how to insulate its appointments from special-interest lobbying.

* Restore the design requirements it has weakened.

* Fully include the public in all of its discussions and findings.

In its present form, however, this Downtown Master Plan should NOT be adopted by City Council.

Where were the tree lovers when the Health Adventure was clear cutting 5 acres in Montford?

Thank you Mountain Xpress, thank you David Forbes and thank you Steve Rasmussen.

The biggest concern from many is the downtown management entity which the plan calls for the city to create and establish. Often these are known as BID’s (business improvement districts)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Business_improvement_district

Here is a link to the state of NC’s downtown management page, which gives more insight to the benefits in creating something like this:

http://www.ncdda.org/

Sorry about the fiery language, but sometimes you just have to send up a distress flare. I agree with many who say the ADD could be a good thing, but only if its powers are carefully and transparently checked-and-balanced and if its board membership is diverse — i.e. not confined to property-owners, as these BIDs often are.

We Ashevilleans need to stop fearing our diversity and start seriously recognizing how much strength and resiliency it gives us. Unfortunately there’s still a strong tendency here to confine the power and decision-making to “our little in-group,” especially when it comes to development issues.