“Two more accidents occurred the following week on Shanty Mountain,” writes local author Ron Rash in his latest novel, Serena (HarperCollins, 2008). “A log slipped free of the main cable line and killed a worker, and two days later the skidder’s boom swung a fifty-pound metal tong into a man’s skull.”

While Rash’s sweeping, big screen-worthy tale is far more then a gruesome account of the human and environmental costs of large-scale logging, Serena is underscored by a violent (though riveting) malevolence. In its opening pages, a brutal murder takes place, setting the tone for the book’s characters. For the sensitive reader, this is a novel likely to induce frequent wincing: Even the author was not immune to the book’s dark grip.

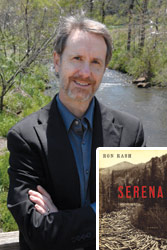

“It took me a while to recover from it,” Rash admits. It also took him three years to complete the heavily researched story, set in Waynesville during the Great Depression.

“I worked probably twice as heard on this book as on any other novel. I went deeper into it than any other book,” he tells Xpress. “I hope it affects the reader.”

Serena centers on the timber industry that clear-cut large swaths of Appalachia—a bittersweet prospect, as the greedy timber barons who denuded the landscape also provided much-needed jobs in an impoverished economy. But, as Rash aptly notes, those jobs came at dear cost. Ill-equipped loggers, desperate for paying work, risked (and often lost) their lives in unsafe conditions, at the hands of uncaring employers.

While this is a story close to the heart of Western N.C.—it was from these timber barons that the exhausted land was purchased to form the now-lush Great Smoky Mountains National Park—Rash adds an intriguing twist in the form of the book’s title character.

Serena, a cold-hearted business maven (and, simultaneously, a pre-feminist super-woman) dreams of owning and exploiting exotic-species forests in Brazil. The means to that end is to harvest as much of the Appalachians as she can get her hands on, and she manages this through a fortuitous marriage to timber camp owner Pemberton. Pemberton (Rash’s male characters are always addressed, locker room-style, by last name only) cuts a formidable figure, but Serena—with her cropped hair, trousers and forthright speech—is immediately pegged by the loggers as a comely demon.

And still the idea of such an influential woman, at that time in history, is exciting. American women only gained the right to vote in 1920, just a decade or so before Serena began her iron-fisted rule of Pemberton’s timber camp. And though Rash can’t quite claim to liking his heroine, he acquiesces a certain awe of her.

“Serena struck me as one of these characters who has an odd integrity. She has an idea she’s very loyal to, at the cost of her humanity,” he said.

Rash, who also authored The World Made Straight, Saints at the River and Out of Eden, solidified Serena’s character by giving her an eagle which she trains to kill lethal rattlesnakes. In order to polish the scene where Serena domesticates her bird of prey, Rash contacted one of only a dozen or so hunters in the U.S. who works with eagles. It’s that sort of book: no mere work of fancy, but a detailed journey into history.

Indeed, Rash’s efforts are fast gaining recognition. Less than two months off the presses, Serena was named among the Publishers Weekly “Best Books of the Year” and climbed to the number seven slot on Amazon.com’s list of the 100 best books of 2008.

The world of Serena is one so devastatingly complete, Rash’s voice so intentional, each detail ripe and important, that the novel would climb charts is no surprise. However, the idea that the author—a professor at Western Carolina University—was a literary late bloomer is more novel.

“I started writing at 23 but was almost 30 before I wrote anything that was remotely readable,” he reveals. “What a lot of people underestimate is endurance.”

The writer’s steadfastness is evident both in his commitment to the dialog (phrases like “thought you might be needful of something to eat” and “buttermilk would be my rathering” pepper the text) and to the book’s vision. Of the former, Rash explains he collected colloquialisms from older relatives who lived near Boone as well as oral histories and Appalachian dictionaries.

Of the latter: “I had an image of a woman on a white horse.” Complete the book and the importance of this dream is made apparent.

Equally obvious is Rash’s strong connection to place. Raised in Boiling Springs, N.C., the author writes of what, and where, he knows best. “I believe what Eudora Welty said: One place understood helps us understand all other places better,” he notes. “Occasionally I do send a character or reader outside the South, but I feel like my work will stay in the South; specifically Appalachia.”

Rash adds (and his recent accolades confirm), “I hope what I’m writing transcends the setting.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.