While watching Fritz Lang’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1932), I was consistently amazed at how modern it comes across today. Yes, its worldview is very much informed by the Germany of the ‘30s (it was banned by the Nazi government), and it very much — due to the technical limitations of the time — looks and moves like a film made in 1932. But so much modern entertainment has roots in this picture, whether it be television police procedurals or the seemingly final sanctuary for evil geniuses: the superhero flick. And all of this would be fine in and of itself, except to top it off, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse is simply one of the neatest movies ever made — overflowing with style and nifty camera tricks — and demonstrates why Lang was one of cinema’s greats.

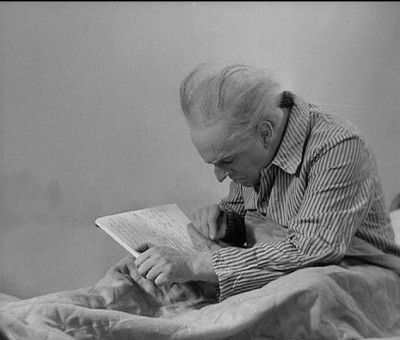

Testament is the second of Lang’s Mabuse films (sandwiched in between Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler (1922), and Lang’s final film, The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960)), it operates in the mode of the cinema’s popular serials of the time, behaving first and foremost as an entertainment. Because of this, the movie (thankfully) lacks any self-importance, and any intentions of weightiness remain in the background. The story follows a handful of different plots, like counterfeiter Thomas Kent (Gustav Diessl), who’s attempting to go straight, and the hard-nosed, clever Commissioner Lohmman (Otto Wenicke), who’s trying get to the bottom of the vast conspiracy at the heart of the story. (Both actor and character who also appeared in Lang’s 1931 film M.) Much of the film — in a post-modern move — is seen through the eyes of henchmen who know little of their purpose and constantly question why they’re asked to commit the crimes they do. We meet Dr. Mabuse (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), a former genius criminal mastermind and expert hypnotist, who is locked away in an asylum in a sem-catatonic trance. He sits in bed all day, scribbling out a blueprint for creating a vast “empire of crime” that will throw the civilized world into a state of chaos. The asylum director decides to enact this plan himself (as a parallel of Hitler and Mein Kampf, this is where the Nazis took exception to Lang’s film).

Testament works both as pertinent treatise and straight popcorn flick — complete with explosions, shootouts, and car chases — while Lang directs with flair and abandon. The real draw is the visual avenues Lang wanders down, from the Caligari angles of a committed patient’s hallucinations, to the ghostly specter of Dr. Mabuse himself, which is still one of the creepiest things ever committed to film. The movie almost manages to single-handedly refute the ideas of the misinformed that old movies are all stodgy or boring. One could — if they were so inclined — call this the ultimate movie, one whose importance lies in showing us the power of visual style, all while reminding us that movies can both be fun and aim for something loftier.

This just shot to the top of my to-watch list.

Great pick, Justin. Gosh, I may even make it out two Tuesdays in a row.

I must say that this pick (and one other) surprised me (agreeably in both cases). I knew he was favorably impressed when we screened this for ourselves once, but I didn’t know it had made this strong of an impression.

I didn’t know it had made this strong of an impression.

It’s just a neat movie. There should be more neat movies.

I certainly won’t argue with that. But it’s a kind of dirty word in cineaste land.

So, that’s where we are?

Well, I’d say the fringes. I often feel like Chaplin at the end of The Pilgrim — trapped on a border and not quite at home on either side.