A new show at UNC Asheville’s Highsmith Union Gallery has revived a conversation some might have thought improbable in Asheville — that of artistic censorship. It’s even resulted in an upcoming panel discussion on the show’s theme and of violence, sexuality and the comparison of artistic intention and censorship.

Asheville artists Valeria Watson-Doost and Jeremy Russell opened Whole Earth Theory: Dimensions of Life and Death on March 1 with a presentation more explicit than most UNCA shows. Russell’s pieces play on psychological/social domineering using materials and imagery historically associated with poverty and mob rule. Watson-Doost, on the other hand, focuses on sexual orientation and repression through Web photos, clothing and lingerie. She’d initially planned a partially nude butoh performance, but scrapped the idea after learning of the restrictions that would be placed on such an event.

And then there are the dildos — several dozen of them, cast in plaster and piled beneath a hanging corpse.

“To this end, it was decided a few weeks ago that a ‘mature content’ sign would be placed at the door of the exhibit,” Holly Beveridge, director of Cultural Events and Special Academic Programs, told Xpress. “We have no desire or intention to censor artistic expression.”

In true Watson-Doost fashion, she added her own touch with a red lipstick kiss on the sign’s corner.

Some would call it censorship, others a gentle reminder (and for some, even a lure). And while one piece was struck from the show, the reasoning remains a matter of law, leaving the personal taste for the artists and faculty to debate.

“We need to be very mindful of the fact that the HU Gallery is not an academic space, but a very public space that, in addition to serving our own students, has traffic from people of all ages and sensitivities, including minors and very young children,” says Beveridge.

The rejected piece included an assault rifle enclosed in a glass box. Russell fashioned the case in the style of those housing fire extinguishers. It would have read “Break Glass in Case of Crazy F—-,” a timely and taboo reference. And even though the firing pin was to be removed for safer viewing, a statewide firearms clause stipulated otherwise.

“According to N.C. Firearms Laws, guns are, in general, not permitted on school campuses unless carried by law-enforcement officials,” Beveridge says. “The decision was made that, even without a firing pin, we would not allow guns or live ammunition to be brought into the UNC Asheville student union.”

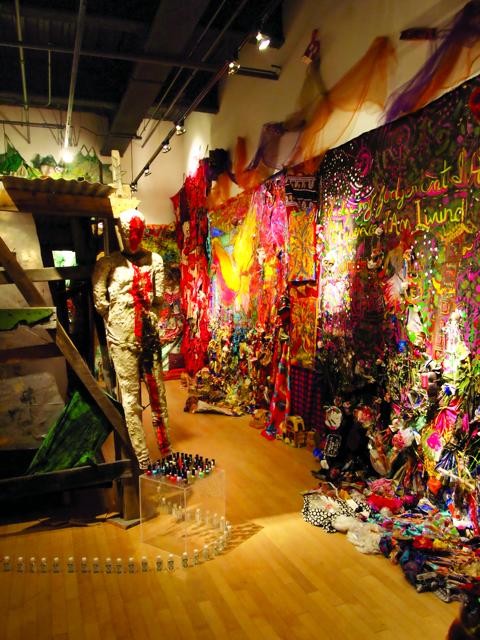

Even without nudity or weaponry, the show warrants dialogue. “If you take a fast look, it’s a beautiful show,” Watson-Doost says, referring to the rainbow-like colors cast across the gallery’s walls. “But a close look reveals pain and suffering.”

She’s covered nearly every square inch of the walls in a psychedelic spattering of toys, pictures and a rainbow-like arc of silks and chiffons. The content, though pretty, is soaked in suffering — by Watson-Doost, but also at large.

Each yard of material casts a net littered with symbols of gender and sexual re/oppression through the decades. Brassieres, underwear and personal garments of every shape and size join erotic imagery and archetypal childhood toys like Barbie dolls, ponies and miniature castles. Plastic guns and a toy laptop are here for the boys.

A circular path is wedged between the walls and a shack in the center of the gallery. Its simple wood construction is clad in plastic tarps and torn cloth. In the middle of this makeshift shanty, which Russell built on-site, stands a black pyramid.

An “open” sign invites you under the cage-like frame and into the dark enclosure, where one is immediately overcome by black-lit images of nebulas. The effect is tactfully disorienting, making both the entrance and exit purposefully difficult.

Outside the dark abyss are four wire-framed and canvas-wrapped corpses, each hanging from one of the shack’s corners. “Lynched” is a more appropriate term. Their hands are bound behind their backs. And each is hung by the neck with framing wire — the same type used for hanging fine art. It offers a grim comparison to early 20th-century mob lynchings that served as a horrifying form of entertainment.

Small piles of diverse objects sit by their feet. Each pertains to a specific societal motif. “Fame” is accompanied by nail polish, “profit” has marbles and “power” is surrounded by bullet casing and latex gloves, among other visual references. It’s the fourth corpse, though, that caused the most fuss. That’s where the plaster dildos are piled, just beneath the “sexuality” victim.

“These are types of institutions that all cultures universally accept,” says Russell. “They cause us to undermine our ethics. And everyone does it, including ourselves.” And, apparently, the individuals that have been stealing these pieces from the show — Russell says many of these additions have dwindled since the opening.

But rest assured, a protective barrier guards viewers from any real harm. Several hundred airplane-friendly, 2- ounce bottles of hand sanitizer form a small fence around the shack.

Russell, a UNCA alumnus, wants to keep the piece moving through the academic circuit, which he considers to be an authoritative and progressive source of problem solving. “I feel that we did some very good work discussing and addressing complex, important issues and seeing them from different sides, and evaluating them from multiple perspectives,” says Beveridge, “[that] is the hallmark of a liberal arts education.”

Bringing the conversations to a university’s front door is Russell’s goal. “It’s these dialogues that break these topics down,” Russell says.

A formal discussion of boundaries

While the lead-up to the exhibition was heated, both parties made diplomatic concessions and compromises. And throughout this process, multiple students became involved in the dialogue, including Jozef Lisowski, an intern with the Highsmith Gallery. In the past few weeks he’s organized a discussion panel set for Monday, March 25 at 6 p.m. in the Highsmith Student Union’s grotto.

“Boundaries: Art and Its Relationship to Systems of Oppression” is free to attend and will explore “the role of art in providing alternatives to tacit sexism, racism and classicism,” according to a press release. Current panelists include Russell and Watson-Doost, professors Dwight Mullen and Lori Horvitz and professor and artist Brent Skidmore.

Whole Earth Theory is up through March 29. For more information, see http://cesap.unca.edu/calendar.

— Reach Kyle Sherard at kyle.sherard@gmail.com.

Thanks Asheville, UNCA and Mountain Express for your support of local artists.

I am sooooooo sorry I will not be able to see this show. It sounds incredible and profound. Maybe Asheville is finally fulfilling it’s claim to being an art town. Art challenges the viewer to stretch the mind and question preconceptions…the rest is simply decoration. Rainer Doost Ph.D.

I am sooooooo sorry I will not be able to see this show. It sounds incredible and profound. Maybe Asheville is finally fulfilling it’s claim to being an art town. Art challenges the viewer to stretch the mind and question preconceptions…the rest is simply decoration. Rainer Doost Ph.D.