UNC Asheville’s Center for Diversity Education is spearheading efforts to have a new monument constructed in Pack Square, in tribute to the contributions and history of Buncombe County’s African-Americans.

According to a petition circulating in support of this effort, the restoration plans for the Vance Monument are an opportunity to stop the pattern of commemorating certain facets of our history while ignoring the experience of other communities. Addressed to the Asheville City Council and Buncombe County Commission, the petition asserts that, with the abundance of Confederate heritage markers in downtown Asheville, it is time for there to be one dedicated to the county’s African-Americans.

“There are five markers for the Confederacy and none for the contributions of the African American community,” said Deborah Miles, director at the Center for Diversity Education. “Why is that? What do we choose to remember? What do we want to forget?”

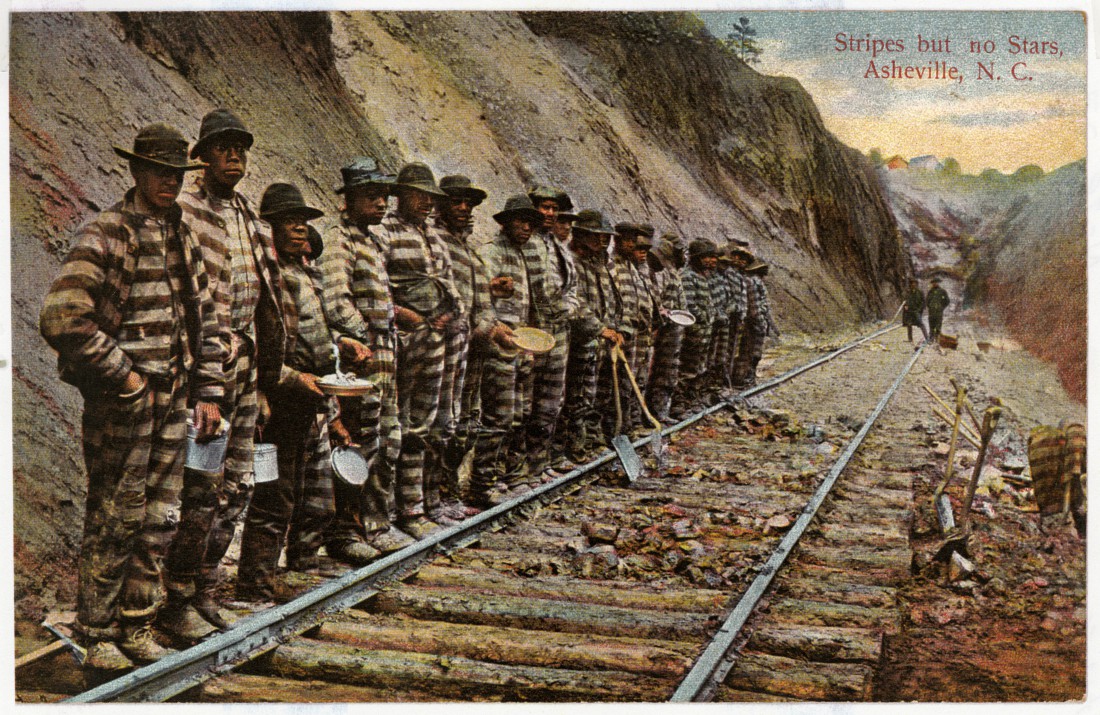

Miles said the Confederate heritage markers in downtown Asheville were introduced during the time the Jim Crow movement was emerging – a movement to deprive African-Americans of citizenship rights. Part of this effort was shaping the public’s historical memory, assuring the right story was told. The creation of this new monument represents an opportunity to balance the scales.

She described the project as being in the informational stage at the moment, getting word out through letters and presentations, along with the petition. Fund-raising and planning committees are still to come. Numerous organizations have signed the petition, including the Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance, the Mountain People’s Assembly, and the Carolina Jews for Justice. Miles estimated it has 1,000 signatures so far.

But Miles said the monument should be iconic – as iconic as the Vance Monument, situated at the heart of downtown Asheville. So the plan is to work with the Arts Council and reach out to the community for the monument’s design.

Darin Waters, history professor at UNC Asheville, speaks of the significance of the public’s collective historical memory, and the ways in which it is shaped.

“Most people don’t get their history in a classroom or from books, the way we do as academics,” Waters said. “They get it from what they see on a daily basis, in the naming of roads and the naming of buildings; in statuary. Things like that. And if you look at the way that is at present, in most places – Asheville is not the only place that I would point to with regard this – but in most places, you don’t see the African American presence in those spaces. You don’t see the memory of African-Americans in those spaces.”

Waters does not know what the monument might eventually look like. However, he points to the controversy over the Unsung Founders Memorial at UNC Chapel Hill as a potential learning experience. There was an issue with the size and positioning of the monument, people believing it to not be prominent enough, especially when compared to the Silent Sam monument nearby, which stands 20-feet tall and honors confederate soldiers.

Waters speculates such monuments are marginalized because people do not like confronting unfavorable aspects of their history. But he feels it is necessary to do so. He holds the Jewish community as an example, in how they pay tribute to not only their history’s achievements, but its legacy of horrors and injustices.

Drew Reisinger, the Buncombe County register of deeds, agrees with that notion, and so unveiled the Buncombe County Slave Deeds webpage in 2013.

The page features an index of slave transactions – showing the grantor, the grantee, and the names of the slaves. These were discovered by combing through property records, looking for transactions where the property in question was a person.

“The Slave Deeds project was something that helped to remember some of those people’s names who had been forgotten by time,” Reisinger said.

Reisinger said there is a tendency to gloss over negative parts of history in public remembrances, particularly in regard to the county’s involvement in the slave trade, and even to outright honor slave-owners and the Confederacy. With a plurality of monuments and thoroughfares in Asheville commemorating notable Confederate individuals and landmarks, these tributes have a marked presence, yet there is very little to recognize the community’s African-Americans and the injustices they suffered.

Miles said the Buncombe County Slave Deeds website was the first step in a plan to create a national database of slave deeds – a Center for Diversity Education program called People Not Property.

James Lee, chairman of the Center for Diversity Education, said Asheville was one of the first communities to desegregate, doing so voluntarily, yet the city has lagged in acknowledging its darker history. The Vance Monument sits across the street from the old site of the county courthouse, where slaves were sold and sentenced to be punished – whipped and hanged. Underneath the ground where the monument now stands, there were once segregated bathrooms. But there is no indication that these injustices existed. Instead there are markers memorializing Confederate soldiers and battlefields.

Mayor Esther Manheimer said she supports the construction of a new monument and appreciates the Center for Diversity Education’s efforts to raise awareness. She also considers the Buncombe County Slave Deed index to be a phenomenal historical record, important in recognizing the county’s involvement in that sordid history.

When it comes time to work with the city to obtain land for the monument’s construction, Manheimer said she is optimistic of the project’s success.

“I can’t speak on behalf of council, because that would require a council vote,” said Manheimer, “but my sense is that the council would be eager to partner with any group that’s interested in memorializing the African American heritage in Asheville, and we’ve already demonstrated that through the establishment of the African American Heritage Commission.”

The only issue she could foresee was in logistics, in coordinating with the upcoming restoration of the Vance Monument. But she said this challenge can likely be overcome.

Professor Waters said in the period following emancipation, African-Americans were not eager to reflect. The scars were too fresh. But now, generations later, the time has come to pay tribute to that legacy, to confront it.

“When we look at the larger narrative of American history, it is still very divided,” Waters said. “And trying to figure out a way of integrating these different stories and experiences into the collective narrative of our history, is work that we’re still involved in. And this, in many ways, helps move us in that direction.”

Thanks for the article – please link to the petition! https://www.change.org/p/asheville-public-art-board-create-a-monument-at-pack-square-to-recognize-and-honor-the-contributions-of-african-americans-to-buncombe-county?recruiter=2962614&utm_source=share_petition&utm_medium=facebook&utm_campaign=share_facebook_responsive&utm_term=des-lg-bing-no_msg

It is ironic that any are deeming the Vance Monument as being somewhat politically incorrect as it was designed by the same person who designed the YMI for the black community in Asheville, Richard Sharp Smith. Do we really have to denounce one part of history for another? There really was a civil war… brave men fought on BOTH sides. The argument was settled. We happen to live in a part of the country where our ancestors were Southern. Lets not treat them as if they don’t deserve to have their lives spoken of or commemorated as lived out to the best of their abilities and understanding at the time in which they lived. Put up a monument for any other deserving fellow citizen but please stop defacing the others or tearing down our own true history around our ears.