The current presidential campaign highlights frustrations many Americans have with the two major parties and their candidates. Onetime presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders has shown that Democrats are not unified under nominee Hillary Clinton on how progressive the party should be. Republican candidate Donald Trump has fractured his own party, with many high-ranking GOP officials declining to officially support him. And a poll conducted by statistician Nate Silver shows there is “record distaste” for both candidates.

Voters’ discontent with the two choices on the ballot may pass with the coming of the new year, but it could also create pressure for a policy window in which ballot access reform could slip through. In North Carolina, nearly 2 million registered voters are unaffiliated, and Buncombe County has 67,875 people registered as unaffiliated. That number gives the county the fourth-highest total of unaffiliated voters in North Carolina and outpaces registered Republicans in the county by 21,085. By comparison the county has 46,790 Republicans, 76,382 Democrats and 1,184 Libertarians registered as of Aug. 20.

Party foul

Currently only three parties enjoy statewide ballot access: the Republican, Democratic and Libertarian parties.

So just what does an unaffiliated or third-party candidate have to do to get on the ballot? The short answer is: Collect thousands of signatures in support of their bid.

North Carolina’s current requirements are broken into two categories: statewide and single-county.

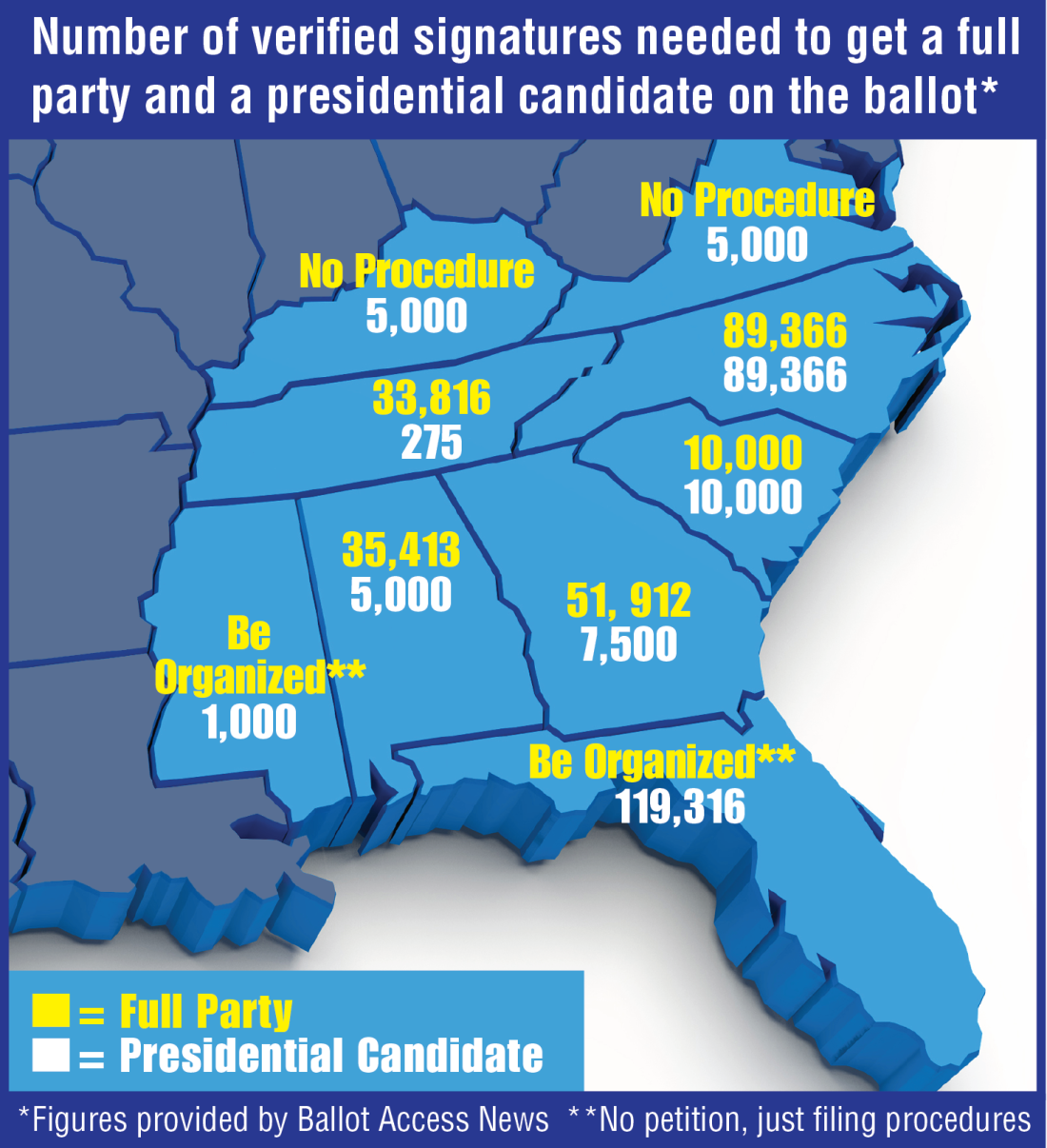

For statewide ballot access, including presidential candidates, a political party must obtain signatures of registered voters equivalent to 2 percent of the total number of votes in the last gubernatorial race, or 89,366 confirmed signatures. Statewide access means a party’s candidate will be on the ballot for any partisan race.

Single-county legislative districts and municipal elections require a number of registered voter signatures equivalent to 4 percent of the county’s total registered voters, or, in Buncombe County, 7,677 confirmed signatures.

In 2016, seven new parties attempted to gain statewide ballot access, but all of those petitions failed to get the number of required signatures. The North Carolina Green Party was closest to success, with 10,484 confirmed signatures — but it still fell about 79,000 signatures short. The party collected 12,877 signatures, but 2,393 were disqualified. Signatures can be deemed invalid if contact information is incorrect, the signer isn’t a registered voter, the information is illegible or for other reasons.

Wayne Turner, co-chair of the North Carolina Green Party, says it had a signature rejection rate of about 18 percent. “This is remarkably good based on past experience. The county boards do a good job of verifying signatures and appear to be dedicated to fairness,” he adds. “Given the ridiculousness of the number of signatures required, the process itself is a wildly unnecessary burden. It has little to do with the sanctity of the vote and a lot to do with making sure the major parties aren’t unduly bothered by challenges from third parties and independents.”

Richard Winger, editor of Ballot Access News and sitting editorial board member of the peer-reviewed Election Law Journal, says, “For president it’s easily the worst state in the country… North Carolina has the biggest number [of required signatures on a petition]. Furthermore, when you compare deadlines, North Carolina has the second-earliest deadline in the country.” The Tar Heel State’s petition deadline is June 1.

“North Carolina has never had a candidate for either house of Congress as an independent on the ballot, and it’s never had an independent candidate on the ballot for governor. There’s no other state that you can say that about,” he adds.

Whatever one’s opinion about the thresholds for ballot access, the current petition process is one of the most accessible in the state’s history. Winger says North Carolina began printing official ballots in 1901, but, “The legislature said the only way to be on the ballot is as a qualified party, and that was defined as one that got at least 50,000 votes for governor in 1900. Well, once you pass a law referring to a past event, it can never change that only Republicans and Democrats can be qualified parties.” He adds that, for about three decades, third-party and unaffiliated candidates had to print and distribute their own ballots.

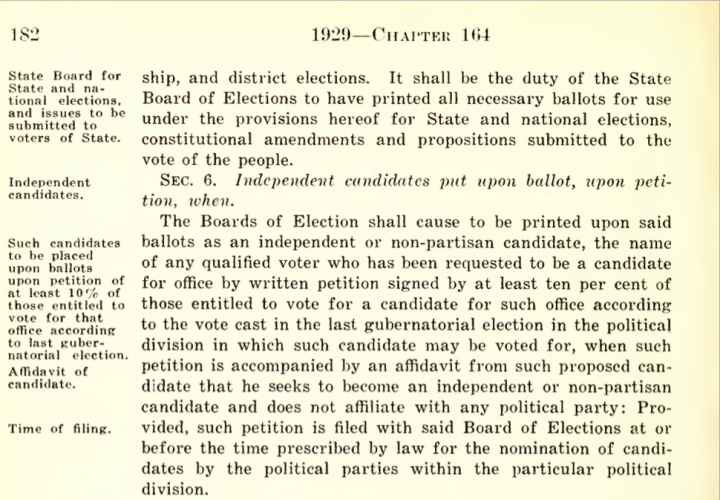

The N.C. General Assembly passed its first law regarding petitioning for ballot access in 1929. That general statute established a signature threshold of 10 percent of the number of people who voted in the last gubernatorial election.

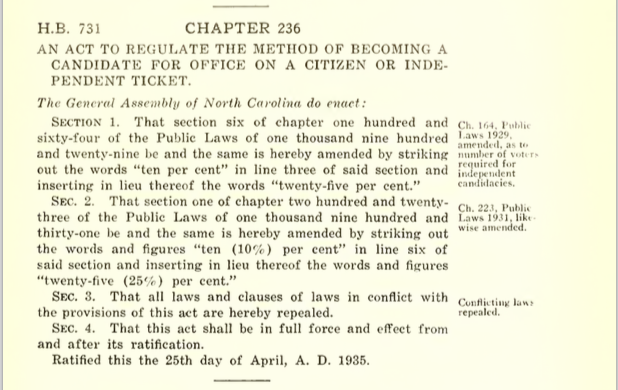

In 1935, the legislature upped the number of petition signatures to 25 percent of those who voted in the previous gubernatorial election, a 150 percent increase. According to Winger, this action was in response to the Socialist Party giving the established political powers a scare when its presidential candidate, Norman Thomas, made it onto the state’s ballot. As well, the state’s attorney general “threatened to prosecute anybody who signed [the petition] who wasn’t an actual dues-paying member of the Socialist Party. He interpreted the law to mean it’s fraud if you signed the petition and you weren’t a bona fide member. Nothing happened, but that just shows you the attitude,” says Winger.

More than three decades went by before the General Assembly modified the law again, and in 1967, the petition threshold to establish a new party on the ballot was set at 10,000 registered voter signatures.

Over time, the 10,000-signature requirement became easier to satisfy, and “outsiders” yet again invaded the ballot. Winger says the Socialist Workers Party made it onto the ballot in 1980. The next year, the legislature lowered the number of required signatures to 5,000. But there was a caveat. “The petition had to have in big print that if you sign this petition and it’s approved, your voter registration is going to be changed to list you as a member of this party. Members of the legislature figured people would never sign as a member of the Socialist Workers Party if they knew they would then get registered into it,” he notes.

Another amendment in 1981 created the addition of a 5-cents-per-signature fee that remained valid until 1999.

Winger believes, over the decades, the increase of signature requirements, addition of fees and other potential barriers were simply reactionary measures by the established two-party system. “Both the Communist and Socialist parties had been organizing as well as they could in the textile mills, and the legislature was afraid they were making headway. Fear drives these things,” he says.

Three’s company

In today’s political landscape, some of those historical reservations about outside parties might still be alive. Nathan West, chair of the Buncombe County GOP, says he’s in favor of ballot access, but not for every party: “Any party or candidate that doesn’t go directly against the Constitution of the United States, like the Communist Party, I think they should have the opportunity to do their petitions and be on the ballot.”

And as far as the requirements for those petitions go, West believes they are fair. “When you’re looking at elected offices in general, they represent the majority. If a candidate can’t get enough signatures to get on as a third party, then we’re not looking at a majority group anyway. Otherwise, we’d have everyone and their brother looking to get on the ballot.”

However, West is also aware of the current mood of American voters and thinks widespread dissatisfaction with the two major parties is contributing to the uptick of unaffiliated voters. “The unaffiliated growth forces, and rightfully so, Democrats and Republicans to re-evaluate their policies.”

Kathy Sinclair, chair of the Buncombe County Democrats, initially agreed to answer questions via email about ballot access. Later, however, she declined to answer those questions or to provide a statement.

Meanwhile, Nate Phillips, chair of the Buncombe County Libertarian Party, thinks ballot access is controlled by the Democrats and Republicans. “I don’t think there is any wrongdoing, but the level where it is set to get ballot access, both county and state, is extraordinarily high and requires [an] extraordinary amount of work for small parties to achieve those numbers,” he says. Phillips adds that the two major parties are hardly recognizable heading into November’s election. “There are factions in these two parties that have become blatantly obvious. They don’t even know who they are anymore, let alone speak for hundreds of millions [of] people.”

To that end, Phillips welcomes more competition. “The more voices, the better. I wish the Green Party had ballot access this year. We want more people on the ballot. In a perfect world, if someone pays a filing fee and legitimately pursues getting elected, they should be allowed to do so,” he says.

Sign on the dotted line

“This system is antiquated. You have disaffected Democrats on the left of the political spectrum who are not represented by their candidates nationally, and you have center-right Republicans who are conservative, but not radical, being ousted by their own party,” says Eddie Milanes, co-chair of the Western North Carolina Green Party. “Given the rise and fall of the Sanders campaign, and people looking for alternatives to Trump-Clinton, we are at a time where the system is falling apart.”

Milanes believes North Carolina’s petition threshold is prohibitive, calling the state “one of the worst … for third-party ballot access.” But he also believes some litmus test is reasonable. “To be clear, ballot access standards should be set in place, but not as restrictive [as those for] states like North Carolina. For someone without celebrity status to run as an independent here would require something close to a miracle to win.”

Phillips says barriers to getting the number of required petition signatures include time, resources and fighting the perception of being an outsider. “It requires a huge investment of man-hours. You’ve got to have someone stand outside the post office all day, or downtown … It takes away all the time they should be putting into their campaigns,” he notes. “When you’re trying to get ballot access, the initial perception is they don’t take you as serious. It’s like they think, ‘If you’re not on the ballot, you’re probably some small party, and that’s good for you, but it’s not for me.’”

And while the Libertarian Party currently enjoys statewide ballot access, it’s a status that’s always in limbo. If the party does not receive at least 2 percent of the overall gubernatorial vote in November, it will lose that access and have to start the petition process over again with new thresholds that will be set by the upcoming general election. However, Phillips is optimistic about his party’s potential turnout: “We feel pretty confident we’ll get 2 percent. Our presidential candidate [Gary Johnson] is polling high and bringing out a lot of Libertarians. I certainly hope we don’t ever have to go back to collecting signatures.” (Buncombe County’s Libertarian Party registration is the fourth-highest in the state, and the party has gained 497 members since 2012.)

Chris Cooper, head of Western Carolina University’s political science and public affairs department, says you’re not crazy if you think Republicans and Democrats don’t want to share the ballot: “It’s in the interest of the two major parties to limit the opportunity for a third party to take away their votes. And the two major parties have actively worked to do just that in all 50 states.”

But he also sees reasonable ballot access restrictions as necessary. “It’s a barrier, for sure. But that’s what it’s intended to be. Most states want to limit the number of candidates on the ballot so your crazy uncle Dan can’t run just because he feels like it,” he notes. “Candidates for major parties have to get through a primary season—and that’s a significant barrier to appearing on a general election ballot. Most states want to make sure that minor-party and independent candidates also have to show organization and viability before appearing on a ballot.”

Where there’s a will, there’s a way

While many people feel the number of verified signatures is excessive, history shows that procuring them can be done. In 2014, Nancy Waldrop completed a successful petition drive to appear on the ballot as an unaffiliated candidate for District 3 of the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners. The threshold for District 3 in 2014 was 2,247 verified signatures, based on a requirement of 4 percent of the district’s 56,187 registered voters.

Her ballot campaign, she says, relied on the help of about 100 volunteers scrambling to collect signatures over about a two-week period. “It was 24-7, and I had a huge support group behind me. You have to have people willing to do the legwork. We went door to door, we canvassed at public places like supermarkets until we were told to leave… It was just people really determined to make it happen,” she recalls. “I really wouldn’t recommend anyone running for office that’s not backed by a political party. I don’t necessarily think that’s good, but it’s the reality.” Waldrop’s bid for office was ultimately unsuccessful.

In addition to garnering the necessary signatures, Waldrop’s campaign had to confront the reality that a certain percentage of those would be rejected, noting that if a hypothetical petition needs 2,000 signatures, it’s best to get upward of 4,000. She says that she encountered myriad reasons a signature didn’t pass muster: “People don’t always know if they’re registered to vote, or if they really live in your district. Very well-meaning people don’t always give you accurate information.”

After completing all the necessary hurdles to get on the ballot as an unaffiliated candidate, Waldrop now feels that North Carolina ballot access law is overly prohibitive. “You don’t want frivolous candidates taking up space just because they have a whim, but I do think there should be a better method, because it does prohibit people with legitimate reasons for running,” she says.

However, Turner, speaking of this year’s failed ballot attempt by the state’s Green Party, says the signatures members collected are “enough in many states to qualify, but [are] only 11.7 percent of the North Carolina requirement. The process requires planning, diligence and hundreds of hours of volunteer time. In the past, we have not used paid signature gatherers.” He cites the going rate for hired help as upward of $3 per signature, a cost that would add up in trying to gain statewide ballot access: “Worst case, not counting administrative and organizing time, and assuming the 18 percent rejection rate, it would have cost approximately $316,000 to get all signatures using paid gatherers.”

Watered-down ballots

A common argument for keeping the current status quo is that third-party and unaffiliated candidates will just take up space on the ballot. Cooper says reducing barriers will lead to a mixed bag of candidates, some legitimate, others not so much. “There are many advantages of a two-party system — it tends to avoid extreme candidates and reward candidates who position themselves in the middle of the ideological spectrum, for example. It also gives voters labels that they tend to understand, even if they may not like them. The question for me is whether it does the best job of reflecting the will of the people,” he adds.

Turner thinks the crowded-ballot argument is a cop-out. “Other states, like California, have many more candidates and parties on their ballot and do not experience these problems. Ballot clutter is an excuse the states use to disenfranchise third parties and independents,” he says.

Winger suggests that implementing instant runoff voting is the “obvious solution” to the watered-down-ballot argument. It’s a style of voting that ranks candidates for each office versus the model of plurality voting, which allows a single vote per office.

Buncombe County’s only unaffiliated elected official, Cecil Bothwell, is also in favor of instant runoff voting. The Asheville City Council member recently left the Democratic Party, but city elections are nonpartisan, so he won’t face ballot access issues should he choose to run for re-election. However, if he eyes a county or statewide post, he would have to align with a recognized party or petition for ballot access.

Bothwell says November’s presidential election is a great example of when instant runoff voting would be ideal: “So if your first choice doesn’t win, you get your second choice. It helps do away with the argument there’s going to be a spoiler.”

Bothwell also notes there is historical precedence for having more than two viable presidential candidates. “It’s kind of strange how restrictive we’ve made this country in terms of parties. If you look back through history, there were four parties running in the presidential election in 1948,” he says. “We’ve kind of reached a dead end in the process. So many people are upset this year about the two major presidential candidates, for different reasons. There’s a lot of people saying, ‘Gee, I wish I had another viable option.’”

Cooper, too, thinks it might be time to ditch our traditional voting model. “I would love to see more potential for third parties to have access, but unfortunately access won’t solve the problem,” he says. “For true reform to take place, we need to rethink the plurality voting system we have and consider going toward proportional representation, or something similar. Otherwise, we’ll get more third-party candidates on the ballot, but they won’t have much more luck winning.”

Turner adds that the current model of voting and more viable ballot options can’t coexist. “The two-party system is the result of plurality voting. It was never built into the framework of the government but evolved as groups of politically like-minded individuals vied for power. It did not become firmly established until the late 1800s but has been entrenched ever since,” he says.

Go ahead, throw your vote away

Phillips says the Libertarian Party is experiencing a surge in people interested in choices outside the traditional, two-party candidates. “People on Facebook say, ‘I don’t like Trump, I don’t like Clinton. Gary Johnson seems all right, how do I learn more?’”

Regardless of the voting model, it will take such genuine interest in third-party candidates to ply votes from the traditional two parties. One major barrier to encouraging that shift is the notion that a vote cast outside the two major parties is a wasted vote.

Phillips is frustrated, hearing so many people talk about voting against a candidate in order for their vote to count. “If everybody who said that actually voted [for] who they wanted to vote for, it would be such a different landscape and possibly change results in the polls,” he laments. Further, he notes that for the Libertarian Party, third-party voting is essential, because having statewide ballot access isn’t guaranteed beyond November if the Libertarians don’t garner at least 2 percent of the total gubernatorial vote. “And if we don’t get that, it will cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and tens of thousands of man-hours over the next few years to regain that ballot access,” he says.

Milanes doesn’t believe in the wasted-vote theory. “Every vote counts, and every person’s voice counts, whether you disagree with them or not. This notion that a vote for X is actually a vote for Y is bullying,” he says. “Third-party candidates can win and have won local offices in the past. Look at Sanders; he was elected as mayor of Burlington, elected into the House of Representatives and U.S. Senate, all as an independent.”

At the local level, Waldrop also believes there are no wasted votes. “Voting makes a difference. One vote in a precinct can sway a whole election,” she says.

There’s also the ideological argument that voting one’s conscious is sufficient, regardless of potential outcomes. As Cooper says, “If a vote is a way for a citizen to express their opinions about politics and government, and who wins or loses is secondary, then it is absolutely not wasted.”

Party on

The question remains: Will widespread dissatisfaction with the two presidential candidates translate to more choices on North Carolina’s ballot?

Bothwell thinks the timing might be right. “The national trend is parties are shrinking and the number of unaffiliated voters is going up,” he notes. “Getting it changed is going to be a hard pull, but I think there’s some interest.”

And Winger thinks it’s only a matter of time before the Tar Heel State sees the writing on the wall. “North Carolina is just looking like an oddity. If people just notice there’s something weird about it, maybe the legislature will change it.”

Turner worries if ballot access reform doesn’t happen, the new petition thresholds triggered by this November’s election could make it impossible for the Green Party to ever see statewide recognition. “We have proposed in legislation that the percentage of participating voters used to determine the number of signatures drop from 2 percent to 0.25 percent. This creates a reasonable number of signatures, about 11,000, and is enough to ensure that no one undertakes this effort frivolously,” he says. “If participation increases in the fall, the next signature requirement could easily run over 100,000. My personal opinion is that the state has no business acting as gatekeeper to the political process.”

The state has discussed ballot access reform legislation as recently as 2009 and 2011. Both times the bills were approved in the House but defeated in the Senate. The Electoral Freedom Act of 2011 would have lowered the signature threshold for statewide access from 2 percent to 0.25 percent of the total number of votes in the 2012 gubernatorial election. It also would have extended the petition deadline from June 1 to the third Friday of July.

The proposed legislation received bipartisan support in the House with former Buncombe County-based Reps. Tim Moffitt and Patsy Keever, and current Rep. Susan Fisher, voting in favor of it. In the other chamber it received bipartisan opposition with former Buncombe County-based Sens. Martin Nesbitt and Tom Apodaca voting against the measure.

As for ballot access being raised in the next legislative session, which begins January, Fisher says it’s a possibility. She adds that there needs to be a signature threshold to keep candidates serious, but she’s open to exploring rolling back that number: “I would definitely give it some thought. I have been privy to a few candidates that have been quite impressive who have gone to the effort to become candidates by gathering signatures. It’s sparked my interest, I will say.”

At the end of the day, Winger believes it’s all about keeping the constant drumbeat of interest going, something he says falls largely on media outlets, noting that North Carolina newspapers aren’t using their editorial voice to shame the legislature. “In other states that have improved their laws it was with newspapers constantly criticizing the old laws. Newspapers in North Carolina have been partly at fault. They don’t pay any attention.”

I’ve said it for many elections- America is the half-wit moron of a country only believing there are only 2 people to vote for.

We’re a nation of Coke/Pepsi and Mcdonalds/Burger King.

More people vote for American Idol than do for elections. Sad.

Anarchist. Think of the chaos if they let just any beer onto the field during “Bud Bowl”. Bud vs. Bud Light is all the choice anyone needs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rzZYVAMpWOs

Your humor is well noted. That video depressed the hell out of me.

Maybe that’s why they never got past Bud Bowl VIII, in 1997… Me? I’m depressed about the election-related videos I watched from yesterday.

Pfft any good alternatives besides Hillary and Trump, besides the goofy guy with the boot on his head?

Hey, lay off Vermin Supreme. He’s not just a goofy guy with a boot on his head – he has a tremendous platform, that I’m sure involves a gigantic toothbrush somehow, but I’m not clear on any of the other details…

Oh wait – that’s right:

Vermin Supreme: When I’m President Everyone Gets A Free Pony

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4d_FvgQ1csE