“We’re certainly not overrepresented,” says Republican Rep. Chuck McGrady, who’s in his fourth term representing Henderson County in Raleigh. In fact, depending on how you break down the numbers, you could say that Western North Carolina falls a little short of genuinely proportional representation on state boards and commissions, according to data obtained from the governor’s office. (Although there’s no universal agreement as to where the region’s boundaries lie, Xpress went with 25 counties, a slight modification of the 27 shown on the Western North Carolina Vitality Index’s map.) And though it’s still early to be drawing firm conclusions, so far this year there are signs that the region might actually be losing ground.

Money and power

The state website for boards and commissions lists 371 such state-level governmental bodies, though not all of them really fit that description. For the purposes of this article, Xpress relied on data from the governor’s office covering 354 boards and commissions. These diverse entities’ duties range from distributing money to formulating policy recommendations to protecting consumers and settling disputes. Some are truly advisory bodies; others have decision-making authority. Further complicating matters is the fact that, in some cases, at least a portion of the appointments are made locally or by some nongovernmental organization, rather than in Raleigh.

To understand the origins of this complex system, you have to look back to the early 1900s, says Chris Cooper, the chair of Western Carolina University’s political science and public affairs department. Back then, he notes, a national progressive movement solidified in opposition to the powerful political machines of the day. “So we put in a bunch of good-government reforms, and boards and commissions were one of them,” Cooper explains. The idea was to get citizens with specialized skills more involved in governmental decision-making.

But while this system may head off a certain amount of backroom wheeling and dealing and bring a measure of everyman wisdom to policy and governance, the members of these bodies are still appointed — usually by such governmental entities as the state Legislature, county boards of commissioners, the state courts and, perhaps most frequently, the governor. And in this respect, some see a resemblance to the old spoils system, in which the victorious candidate felt entitled to reward friends and allies with positions of power.

Clearly, these changes didn’t eliminate hardball politics, but the situation is more nuanced today. Typically, the statutes that establish these boards parcel out the power to make appointments among the various branches of government, sometimes with advice from outside entities.

Nonetheless, Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, is currently butting heads with the state Legislature over the power to appoint a partisan majority to the State Board of Elections, and there’s been plenty of controversy around other appointments as well. Meanwhile, some of the appointments made by Pat McCrory, who Cooper narrowly defeated in last year’s gubernatorial contest, also sparked controversy, even though McCrory’s own party controlled the Legislature.

Various factors come into play when these appointments are made. Members of the Industrial Commission, for instance, earn more than $127,000 a year. And the boards of both the Clean Water Management Trust Fund and the Parks and Recreation Trust Fund “actually make decisions as to how money is allocated,” notes McGrady, which arguably gives them even greater power.

What constitutes fairness?

With thousands of appointments to be made, says professor Cooper (no relation to the governor), “I think it’s safe to assume that for some of these [positions] the governor probably really knows who he’s appointing — and for some he has no clue.” Consider, for example, the state’s Boxing Authority. “I find it hard to believe that Roy Cooper — or, frankly, anyone in the Legislature — knows anything about boxing regulation. Nor do I.” So while some seats might be filled as political favors, the political scientist points out, in many instances, the appointers are simply trying to do the best they can based on the advice they get.

Asked about the governor’s approach, spokesperson Noelle Talley simply said, “We seek well-qualified people interested in public service from all parts of North Carolina, including Western North Carolina, to serve on state boards and commissions.”

A 1997 article by political scientist Jerry Mitchell of Baruch College identified four key considerations that may come into play when such appointments are made (see “Representation in Government Boards and Commissions,” March-April 1997 Public Administration Review): the board’s function and whether it’s supposed to reflect broader public expectations; the preferences of the entity’s management and staff; the appointer’s preferences; and those of the people the appointee represents.

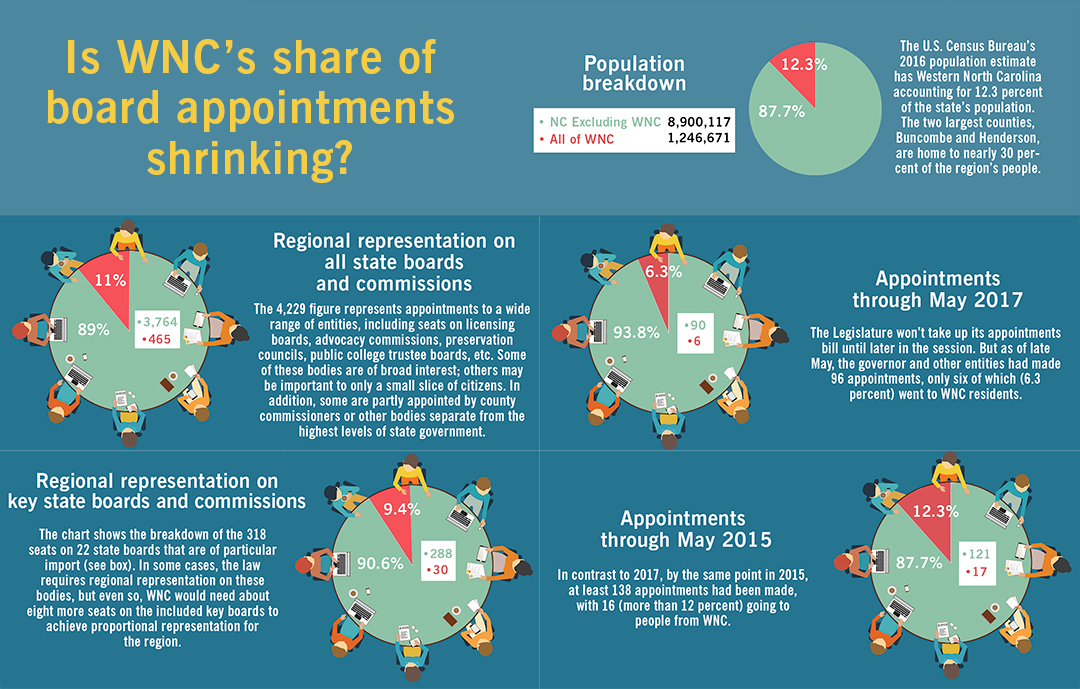

To assess this region’s representation on state boards and commissions, Xpress asked the governor’s office for a complete list of appointees, with their addresses. Based on that data, Western North Carolina does appear to have something close to proportional representation on those bodies. Using the Census Bureau’s 2016 population estimates, WNC is home to about 12.3 percent of the state’s population but less than 11 percent of the appointees to state boards and commissions.

Considering the many variables among the 354 different boards in question and the 4,229 seats they contain, that seems reasonably close. If we narrow the focus to some of the more influential entities, however, the gap becomes a little larger.

Is WNC losing ground?

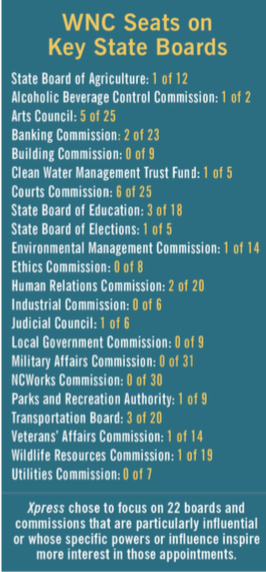

To clarify the picture, Xpress chose to home in on 22 particularly influential boards with a total of 318 seats (see chart, “Regional Representation on Key State Boards and Commissions”). WNC residents account for only 30 of those seats (less than 10 percent).

To clarify the picture, Xpress chose to home in on 22 particularly influential boards with a total of 318 seats (see chart, “Regional Representation on Key State Boards and Commissions”). WNC residents account for only 30 of those seats (less than 10 percent).

Furthermore, one of the most significant boards is omitted from all of these tallies.

Because the members of the University of North Carolina’s Board of Governors are chosen by the Legislature, for example, these highly sought-after positions aren’t included in the data behind the charts presented here. But they certainly bear mention, because the massive educational system the Board of Governors oversees accounts for a significant chunk of the state budget.

And in a controversial election this spring that will usher in a smaller board, at least two WNC residents are coming off the board, including Vice Chair Roger Aiken of Alexander. Carolyn Lloyd Coward of Arden will be added, and Asheville resident (and former mayor) Louis Bissette will remain as chairman until 2019. C. Philip Byers of Forest City rounds out the WNC delegation.

Meanwhile, in Cooper’s first year as governor, only six of the 96 appointments made so far come from the western counties. And two of them, to the Board of Transportation, were required to go to westerners. Still, at least one local lawmaker cautions against reading too much into this discrepancy. “During the McCrory administration, there were probably more western appointments made by the governor than might have been made in other administrations,” says McGrady. “That was not a product of really trying to aggressively get people from Western North Carolina: It was the fact that the guy who was tasked with helping the governor fill some of these slots happened to be from Asheville, way back when.”

Having our say

It’s important to keep in mind that many of this year’s appointments have yet to be decided. State Rep. Brian Turner of southwestern Buncombe County says his staff keeps an eye on these openings, and the governor’s office has reached out to him for input on potential candidates. Turner, a Democrat, says it’s a great opportunity to make sure the people of WNC are represented. Regional representation is required on such key bodies as the Board of Transportation and the Wildlife Resources Commission, which also include at-large seats.

“So we do get sort of our fair share,” he points out. “I know that there are some vacancies or some with a potential turnover coming up, and the governor’s looking at names to fill those. As a general rule, I would always like to have more representation of Western North Carolina. But I haven’t seen where we’ve really been left out at this point.”

Regional bias aside, other practical factors can also affect the region’s representation in the state capital. Sometimes, notes McGrady, “It’s a matter of distance. It’s easier if you live in Raleigh or Durham or somewhere close, where you can jump in your car, attend a board meeting and be home that afternoon. That doesn’t happen with people from Western North Carolina.”

But McGrady also stresses that he’s frequently asked by his party’s leadership for recommendations to fill various openings. “And on a number of occasions, I’ve been successful,” he continues, pointing out that “I put forward Carolyn’s name for the recent appointment to the Board of Governors.” McGrady says he told his colleagues that since another westerner was leaving, they needed to consider geographic balance.

The charts accompanying this story illustrate WNC’s representation by the numbers. But in a complex and ever-shifting situation with many variables, it may not be so easy to quantify how things actually play out in practice when key decisions are being made.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.