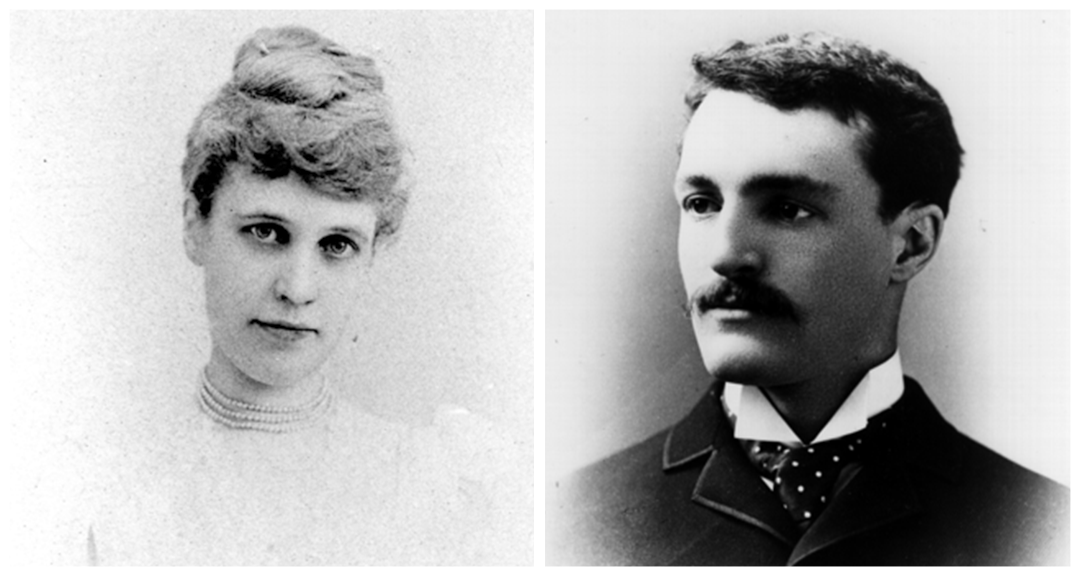

In the preface to her 2017 book, On Strawberry Hill: The Transcendent Love of Gifford Pinchot and Laura Houghteling, writer Paula Ivaska Robbins informs readers that her work is not a biography of Gifford Pinchot, American forester, politician and one-time manager of Biltmore’s forests. Rather, Robbins writes, “This is a story about two people and the place where they fell in love. The place was West Asheville, North Carolina[.]”

Like many in the late 19th and early 20th century, Laura Houghteling came to the area due to illness. After being diagnosed with phthisis in the late 1880s, she arrived to the mountains of Western North Carolina to seek the medical attention of Dr. S. Westray Battle (See “More than a Citizen,” Sept. 26, Xpress).

During this same period, Pinchot came on as a member of the full-time staff at the Biltmore Estate. According to Robbins, George Vanderbilt hired the Yale graduate on Feb. 21, 1892, “to create a plan for managing the forest at Biltmore and to prepare an exhibit of this forest for the World’s Columbian Exposition that would be held in Chicago, opening on May 1, 1893.”

In the early chapters of On Strawberry Hill, Robbins examines the budding relationship between Pinchot and Houghteling. Both were born into wealthy and well-connected families. Houghteling was 28 when she and Pinchot, 26, became neighbors in West Asheville. Robbins suspects that Houghteling’s illness was the reason she had not wed. (Most women within Houghteling’s social class, Robbins notes, would have been married shortly after turning 18.) The writer points out that “[c]onsumption carried a social stigma of being a disease of the slums and lower classes, as well as being caused by a hereditary weakness or familial predisposition.”

Nevertheless, in December 1893, the couple discussed marriage. During this same period, Houghteling relocated to Washington, D.C., on account of her declining health. Shortly thereafter, on Feb. 9, 1894, the Asheville Daily Citizen informed its readers, “Dr. S. Westray Battle has received a telegram bearing the sad intelligence that Miss Laura Houghteling … died yesterday at the house of Senator Stockbridge in Washington City.”

Death, however, would not end Pinchot and Houghteling’s relationship. At the turn of the century, Robbins notes, spiritualism had a strong following. “A core belief of Spiritualism,” Robbins writes, “is that individuals survive the death of their body by ascending into a spirit existence.” This belief, she continues, was especially attractive to individuals who had recently lost a loved one. Pinchot was no exception:

“For twenty years, Gifford secretly wrote about Laura and their ongoing relationship in his private diaries as if she were a living presence who never had left him. She spoke to him, traveled with him, read books with him, advised him, and inspired him.”

Code became standard practice for Pinchot when writing of Houghteling’s spiritual presence. Robbins explains:

“On the surface, the coded entries appear to describe the weather or what kind of day he had. On days that he felt Laura was with him, he would write, ‘a bright day,’ or ‘a clear day.’ If he was having difficulty reaching her but knew that she was near, his usual entry was ‘not a clear day.’ Sometimes there were bleak days when he could not find Laura at all and the code described his pain: ‘a dull, dead day’; ‘a blind day’; ‘a lifeless, useless day’; ‘I’m going blind.’”

Char Miller, author of Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism and Seeking the Greatest Good: The Conservation Legacy of Gifford Pinchot, wrote the foreword to Robbins’ On Strawberry Hill. In it, he notes that Robbins’ work is “the first book-length exploration of Gifford and Laura’s fascinating love affair.”

He goes on to mention the eternal bond Pinchot and Houghteling made to each other prior to her death:

“In a very material sense, Gifford kept his part of the bargain, a lived reality that he recorded almost daily in his diary, that gave shape to whenever he delivered a speech and felt Laura’s enveloping presence, and that he and his mother enacted whenever they visited spiritualists, mediums, and yogis in hopes of contacting his dearly departed. This very personal quest also had a profound impact on his professional career, as Robbins nicely details. In so doing, she gives us a more fully realized Gifford Pinchot: an ardent champion of forestry and a crusading conservationist, his work advancing the public good was fueled in part by his abiding memory of a young woman and the energizing love they shared.”

Did Pinchot marry? If so, did his wife know of his “spiritual” relationship with Houghteling?

Gifford Married in 1914 to Cornelia Bryce, a feminist activist and shrewd political adviser. And yes, Cornelia knew about Laura. Most strikingly, Pinchot’s diary entries about his lost love end just days before his earthly marriage. A fascinating set of relationships!

Thank you for that information.

According to biographical info in Wikipedia, he was married to a lady named Cornelia Bryce but it doesn’t give a date for their marriage or any details except that they had a son named Gifford Bryce Pinchot. It also says that he passed away on 4 October 1946 at the age of 81, from leukemia.