On Jan. 10, 1922, The Asheville Citizen noted a “sadness in the city hall” over the Jan. 8 death of Dr. Lewis M. McCormick. The paper went on to report that the building’s flags, along with those at Pack Square, “floated at half mast in honor of the faithful employe of the city.” At 58, McCormick died suddenly from complications following a bout of influenza.

The reverential outpour that followed McCormick’s death was a far cry from the city’s initial ambivalence surrounding his 1905 arrival in the mountains. By 1906, McCormick earned the nickname “Fly Man.” The moniker was in response to the scientist’s early anti-fly campaign, which aimed to eliminate the insect through improved sanitary conditions at public and private stables.

On April 5, 1906, The Asheville Citizen reported:

“The plan of Mr. McCormick is to stop the breeding of flies at the various stables in the city. It is conceded that the birthplace of the pests are always in these vicinities, and that by the application of the proper chemicals and the use of screens the population of flies can be lessened so that they will be practically exterminated. Numerous citizens are inclined to give credence to the proposition, but since the aldermen have declined to insure the amount required until something is shown of the efficacy of the treatment, it is naturally expected that Mr. McCormick will be permitted to make a thorough test, which will work largely to the city’s good, even if there should remain just enough of the insects to keep certain bald-headed gentlemen from constant slumber.”

While the Board of Aldermen would not finance McCormick’s campaign, it did support the scientist’s efforts through its passage of a fly ordinance. The Asheville Citizen included the new law in its April 13, 1906, edition. Manure exposed on any property within the city for more than six days was now illegal. Flyproof bins were also required at all stables, where manure was to be stored and sterilized every day “with chloride of lime or other disinfectant.” Each violation carried with it a $25 fine.

Despite the new law, some stable owners resisted McCormick’s efforts. Things quickly came to a head. On May 4, The Asheville Citizen stated:

“The first battle in the warfare on Asheville flies is promised this morning in police court, owners of eight Asheville stables have been arrested on warrants sworn out by Mr. L.M. McCormick, asserting that Mr. So-and-so ‘did unlawfully and willfully allow and permit manure to be exposed on his premises for more than six days.’”

Public opinion soon turned against McCormick. On June 16, 1906, The Asheville Citizen published the following anonymous poem, titled “A Soliloquy of the Fly Man”:

There was a little “fly man”

Who had a little fad

Of running round the stables

To see what would be had.He routed out the muck-heaps,

And turned them o’er and o’er

Because he saw a little fly

He vowed there must be more.He put some in a bottle,

In a photographic shop,

The muck stayed on the bottom,

The flies were on the top.He asked the Pack Square loafer

To stand and watch them grow,

The loafer stood for ages,

Then turning round did go.The fly man took out warrants

To help his little game,

They made him a policeman

To put us all to shame.They gave him heaps of dollars,

(To humor him they say),

But flies still come and go, boys,

In thousands, every day.So watch out for the fly man.

He’s a Scotchman — father’s side —

“There are twenty-three flies living,

All the rest have died”So he’ll tell you: Don’t believe him,

He has got you on a string.

To let him prove his statements,

Make him bring the dead ‘uns in.You may travel right through Asia,

Europe, Biltmore and the rest,

But you’ll never, NEVER, NEVER

Rid us of this little pest.

By summer’s end, McCormick’s proposed solution to exterminate the city’s flies proved futile. But on Dec. 8, The Asheville Citizen reported that despite the initial setback, McCormick still believed he could turn the city into a “flyless Eden.”

Years later, on Sept. 19, 1915, McCormick addressed the Public Health Administration Section of the American Public Health Association in Rochester, N.Y. In it, he highlighted Asheville’s overall drop in the number of cases of typhoid fever. In 1911, the city reported 17 instances; by 1915, there were only two. McCormick attributed the decline, in part, to the ongoing fight against the housefly.

In the same speech, McCormick implored his audience to remain active and vigilant against the insect. “Swat the fly, swat him before he gets his wings — poison, trap, screen, but above all clean up and keep clean,” he declared.

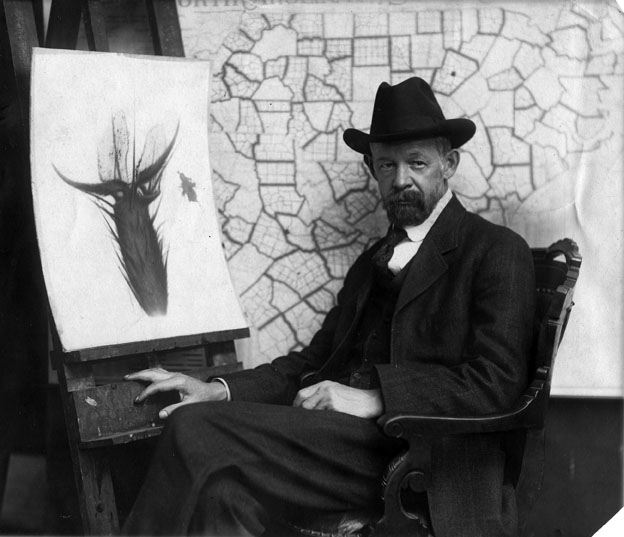

McCormick’s dedication and persistence were among the noted attributes reported after his death. On Jan. 10, 1922, The Asheville Citizen described him as the country’s first scientist “to make a serious business of the campaign against the house fly.” The article went on to note:

“His revolt against these carriers of disease was at first received with good-natured ridicule: to many it was an effort to set aside the laws of nature, but Lewis McCormick lived to see his fight justified by accomplishment and his methods adopted in many states.”

Shortly after his death, the city would honor the scientist by naming its new ballpark, McCormick Field. The stadium opened April 3, 1924.

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents.

I recall reading somewhere that, for a time, Dr. McCormick paid schoolboys a “bounty” – seems it was a penny apiece – for each dead fly brought to him! He is interred at Riverside Cemetery.

https://images.findagrave.com/photos/2010/184/54489305_127830428040.jpg

Hey Phillip. Good to hear from you and thanks for the picture! The “bounty” does sound familiar, although I don’t know if it came up in any of the newspaper articles I found. Thanks as always for reading Xpress and sharing with us your insights and thoughts.