Over the years, its name has changed. What began in 1918 as the U.S.A. General Hospital No. 19 is today the Charles George VA Medical Center. The facility’s treatment focus has shifted as well. During World War I, tuberculosis drove the site’s initial construction. These days, the center treats physical and mental health issues impacting the 48,000 veterans it serves each year.

On Friday, Oct. 26, at 11 a.m. the Charles George VA will celebrate its centennial at its grand reopening of building No. 9. Formerly the white nurses’ dormitory, the 1932 structure sat vacant for the last 44 years. But in 2016, a $9 million restoration project paved the way for the building’s latest rendition as the Hope and Recovery Center. With a focus on mental health, the site’s top priority is suicide prevention.

The ribbon-cutting, says Armenthis Lester, the medical center’s public affairs officer, will include remarks from VA leadership, as well as information on available programs. The gathering will also feature a Cherokee warrior dance, along with displays and exhibits of historical images and artifacts from the site’s former days.

The N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Western Office, which occupies the former black nurses’ dormitory adjacent to the Hope and Recovery Center, will also participate in the grand reopening.

Heather South, lead archivist at the Western Regional Archives, says she and her colleagues have had the unique opportunity to watch the former sister dormitory slowly be brought back to life. “To see it go from abandoned shambles to revived services has been an amazing transformation,” she notes.

Early unrest

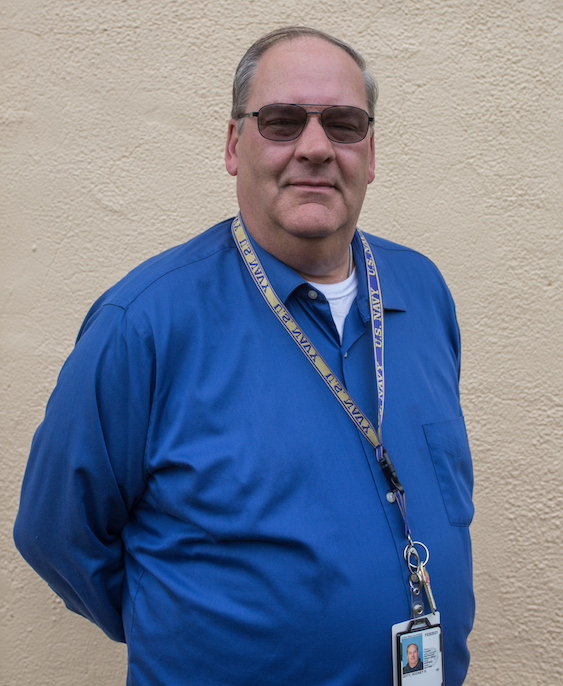

“There’s a lot history here,” says Rod Doty, the VA’s digital library technician. Not surprisingly, he adds, the facility has seen plenty of change. The original wood-frame structures once scattered across the site’s former 346 total acres have all been razed, although a few relics do remain, including an original foundation on the southern slope of Bull Mountain.

In 1918, Doty says, that entire section of the mountain was clear-cut. Since then, Mother Nature has gradually reclaimed parts of the VA’s former property (which today totals a much-reduced 64 acres). “What you’re seeing now [on Bull Mountain] is 100 years’ worth of growth,” he explains.

While Doty’s historical knowledge stretches the entirety of the hospital’s 100 years, his focus for the centennial has been on the site’s earliest days. A completion report from June 1, 1919, has provided him with a detailed account of the original project’s scope, as well as some of the challenges faced during constructions initial stages.

Work officially began on March 25, 1918. Local construction crews were hired, and local car owners were solicited to transport these men to and from the site. Compensation began at 15 cents per passenger, but disgruntled drivers soon demanded and received increased pay.

Unrest quickly spread beyond the weary drivers. Carpenters, electricians, plumbers, steamfitters, sheet metal workers, plasterers and painters all demanded higher wages. In each case, the government eventually acquiesced to avoid labor shortages that might impede the site’s timely completion.

By August, the original project’s 1,000-bed enterprise was 97 percent done. That November, all remaining duties — including completion of the remaining dorms, sewage system, water supply, heating distribution, outside electric wiring and vehicle roads — were wrapped up. Additional wards were built in 1919. Upon their completion, the site had 102 total structures, including offices for the YMCA, Red Cross and Knights of Columbus (see “Asheville Archives: Construction begins on U.S.A. General Hospital No.9,” Oct. 17, Xpress).

“They had everything,” Doty exclaims. But only after the infirm soldiers arrived did the city within a city truly take shape.

‘An unseen enemy’

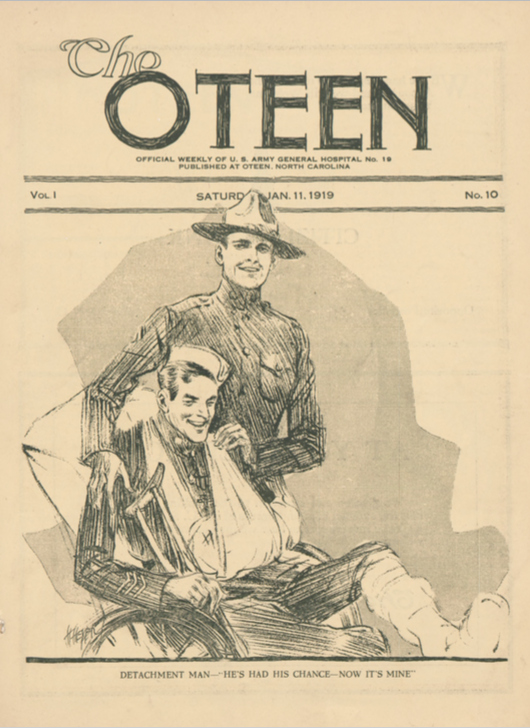

“It begins to look like most of us have been chosen to help our country by fighting tuberculosis rather than by fighting the Germans,” wrote Maj. W.G. Turnball, in the Nov. 9, 1918, debut publication of The Oteen, a weekly paper published by General Hospital No.19. “To many this has been a disappointment. The glamor, the excitement, the hero-worship are lacking, and we feel we are not having a direct part in the great victory that is being won. We do not deny that this work is necessary and that someone must do it, but it is not exactly what we wanted to do ourselves.”

For a year, The Oteen sought to keep patients and staff motivated and up to date on the latest news both on and off the General Hospital No. 19 campus. The publication included hospital gossip and previews of upcoming social activities, as well as pertinent information regarding their illness, treatment options and Army benefits.

For contemporary readers, the publication also provides unique insight into the daily lives and worries surrounding the VA’s original patients. Time and again, the paper seeks to address and reassure soldiers of their latest mission: recovery.

Unlike German foes, tuberculosis was “an unseen enemy.” No vaccine existed at the time. Instead, hospital doctors called for plenty of rest, air, food and exercise, or as The Oteen put it, “the quartet of legs that the cure for tuberculosis rests so securely upon.”

The war was over by the time The Oteen published its second issue. Germany surrendered on Nov. 11, 1918. But in keeping with its motif, the paper asserted that the battle against tuberculosis carried on. “It is just as deadly and to some of you it means that you will have to fight as hard as though you were or had been in the front line trench,” the paper declared.

Although Doty believes the publication was limited to on-site distribution, some of its articles suggest a broader audience. One piece, published in the issue of Dec. 7, 1918, implores family members to help establish a more positive outlook among patients through their letters.

“It is a difficult problem to care for men in a hospital whose one great desire is to go home,” the article states. “This problem is too often made doubly difficult by the nature of the letters which the men receive from home. If, instead of thinking up every possible home trouble to write these men, the people at home would write cheerful letters, it would do much toward maintaining a cheerful atmosphere in the Hospital and thereby helping each man on to a cure.”

In another issue, contributing writer Capt. B.L. Hayes offers a detailed account of the daily activities and duties for those enrolled. The piece, titled “A Letter for the Folks at Home,” concludes with an assessment of the men’s overall attitude toward the institution.

“It is not unlike that of the pupils in a boarding school,” Hayes writes. “It has been well summed up in the following words: ‘Taking things as they find them. Vaguely understanding. Caring less. Grumbling by custom. Cheerful by nature. Ever anxious to be somewhere they are not. Ever anxious to be somewhere else when they get there.’ Living through a period which in after years will be remembered as the happiest of their lives.”

Warrior’s legacy

The images and artifacts at the Oct. 26 ribbon-cutting for the Hope and Recovery Center will focus primarily on the VA’s original days as U.S.A. General Hospital No.19. But the ceremonial Cherokee warrior dance will call attention to the region’s original inhabitants, as well as the medical center’s namesake, Charles George.

George, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, served in the Army during the Korean War. On Nov. 30, 1952, the private first class died in battle after throwing himself onto a live grenade to save the lives of two fellow infantrymen, Marion Santo and Armando Ruiz. Two years later, George was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor — one of only 32 Native Americans to have received the highest personal military decoration.

On Nov. 15, 2007, the former VA Medical Center was officially renamed the Charles George VA Medical Center. Warren DuPree, an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee and a retired Navy veteran who served in both Vietnam and Operation Desert Storm, remembers the day. “Native Americans have always been a warrior society,” he says. “So naturally the Cherokee people were extremely proud … to have [Charles George’s] name remembered forever in a medical facility that provides services to the men and women of the United States Armed Forces.”

Eight years later, DuPree helped establish the Charles George Memorial Project Committee. Over the course of several months, the organization raised $50,000 for the creation of two life-size bronze statues of the fallen hero. Throughout the process, the project’s sculptor, James Spratt (a retired Vietnam veteran), was undergoing treatment for bone cancer at the VA.

On Sept. 24, 2016, the first sculpture was unveiled at the medical center. At that time, Spratt was receiving hospice care at the facility’s Community Living Center. “He passed away 10 minutes after we began the dedication,” DuPree remembers. “It was very emotional.”

That November, on Veterans Day, the second sculpture was dedicated at Cherokee Veterans Memorial Park. “We now have these two bronze sculptures of a tribal treasure and a national hero that are facing each other,” DuPree explains. “There is tremendous power in that.” Both statues, he adds, look from a great distance toward the Yellow Hill Veterans Cemetery, where both George and Spratt are interred.

The next 100 years

As Doty approaches the recently completed Hope and Recovery Center, he takes a moment to consider what the building once was compared to what it now is. Not that long ago, he remembers, parts of the structure’s slated roof were caving in. Vines climbed down from the building’s gutters, gathering at its center to create a sort of widow’s peak. But these days, Doty observes, “it’s pretty majestic.”

The new facility, notes Lester, will help the Charles George VA continue to serve the approximately 8,000 veterans who seek treatment each year through its outpatient mental health clinic. According to the latest available VA National Suicide Data Report, the suicide rate among veterans in 2016 was 1.5 times greater than that of nonveteran adults. That year, 7,298 current and former service members took their own lives, and suicide rates among veterans ages 18-34 years old continue to increase.

Treatment for those struggling with suicidal thoughts is available through the Charles George VA, Lester emphasizes. The ongoing goal for the organization, she says, “is to get to zero suicides.” Information on enrollment and eligibility will be available at the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

Lester sees the day’s events as a bridge between the site’s past, present and future. “We’re really excited about the connection that we have with the Cherokee Nation and the history of the area,” she says. The Hope and Recovery Center, she adds, is simply the latest in the organization’s long-standing effort to improve the lives of service members. “The building cares for our current warriors and those who will come in the future,” she says.

For South, a similar connection exists. “They built what amounts to a small city from sprawling farmland in a matter of months,” notes South. “Veterans are still being served 100 years later on the same grounds. Nurses, doctors, visitors — think about the number of people that have had a connection to this exact place. It is impressive. I am just glad that I can be part of that continued history and help preserve some of the story for the next century.”

This is a great article — but it fails to state the actual time of the event. Or is it so buried I can’t find it.

Thanks for the comment. The event starts at 11 a.m. I’ve added the information to the piece. Thanks again.

Thanks!