(Editor’s note: Portions of this article first appeared in Hidden History of Asheville, a book written by the staff and volunteers of Pack Memorial Library’s North Carolina Room and published last year.)

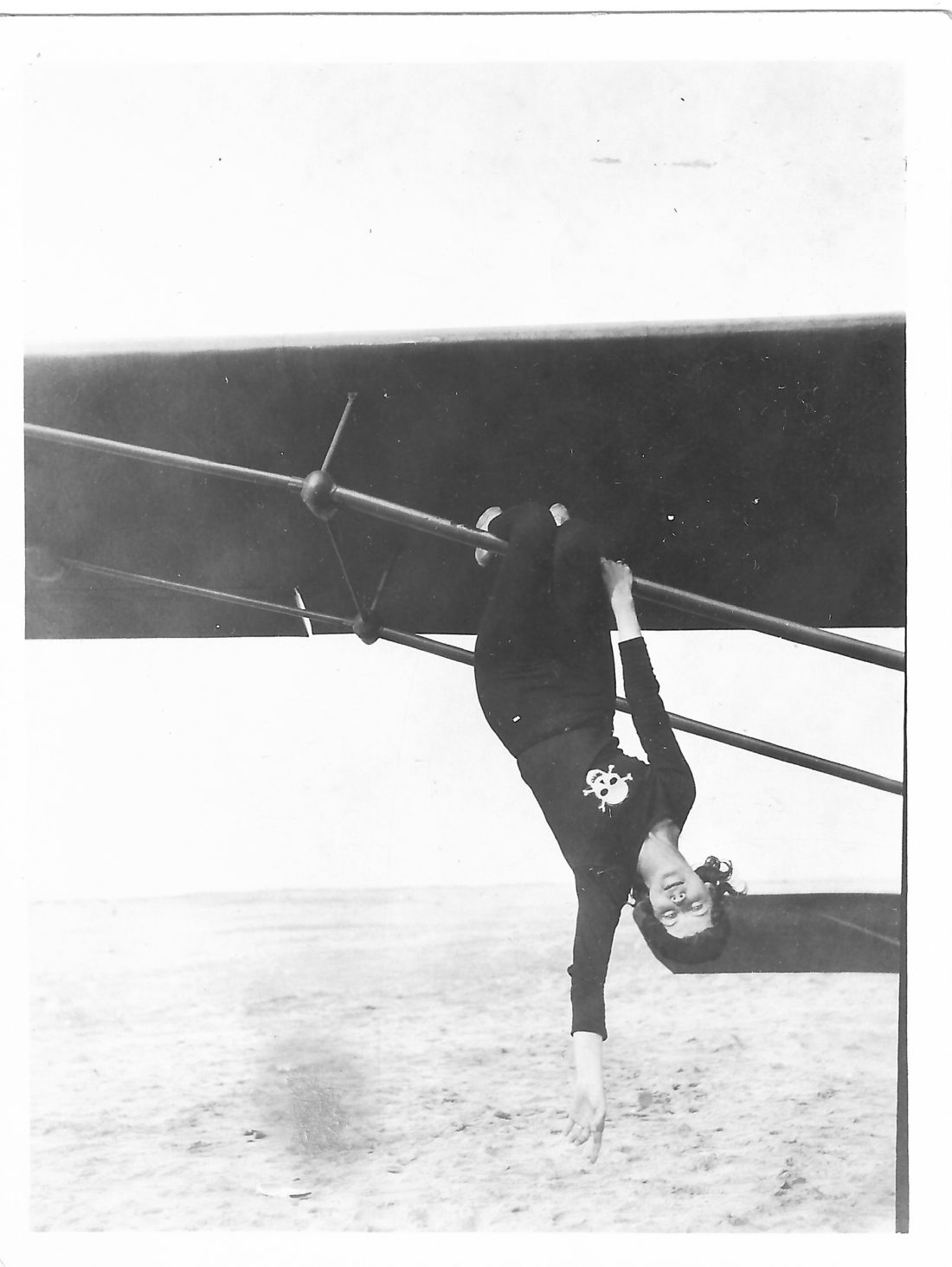

Pity anyone who tried to keep up with Uva Shipman Minners, who carved a blazing path through 1930s America. The “aviatrix,” as she was called in the parlance of the day, was not only a groundbreaking woman stunt pilot, parachutist and wing walker: She also raced cars and crashed them with aplomb.

Minners was an early member of the small but spirited sorority of pioneering women who insisted that access to flight controls shouldn’t be monopolized by men. At the time, “A new generation of female pilots was emerging, and they refused to be pigeonholed, mocked or excluded,” historian Keith O’Brien noted in his 2018 bestseller Fly Girls. “Instead, they were united to fight the men in a singular moment in American history when air races in open-cockpit planes attracted bigger crowds than Opening Day at Yankee Stadium and an entire Sunday of NFL games.”

Born Uva (pronounced YOU’-va) Shipman in Hendersonville in 1908, this daughter of a Baptist minister was raised in Asheville before setting her sights on points northward and airborne. In her early 20s, she danced professionally and wed in a self-described “marriage of convenience” that enabled her to move to New York City, according to her only child.

“She always did crazy things,” remembers Hendersonville resident Carol Ann Williams, who praised her mother’s brave spirit before adding, “I think it was foolishness, myself.”

Dave Williams, one of Minners’ grandchildren, has similar recollections. “She was a character, that’s for sure,” he says. “We were lucky to have known her while she was alive; she could have been killed a lot of times.”

From the Big Apple, Minners rose to fame as a dashing daredevil who indeed cheated death. She dazzled crowds at races and air shows, spawning breathless newspaper accounts that spread around the country and made their way back home to Western North Carolina. She was 5 feet, 2 inches tall, somewhat waifish, and by many accounts lovely in appearance. But she had little interest in joining the high-society flappers of her era, preferring to venture where few women (and, in truth, not many men) had gone before.

“Young women today have to be adventurous about the jobs they pick,” Minners said in 1935 during the depths of the Depression. “Because all of the safe and sane places are taken, and one certainly doesn’t want to be a loafer all one’s life.”

She cut her teeth on wing walking, mostly for the famed Howard Flying Circus, and used the proceeds to pay for flying lessons. As one contemporary newspaper account noted, her specialty was “walking out onto a wing and going though acrobatics without any safety attachment while the plane whirled along at more than 100 miles per hour.”

In December 1931, Minners announced an ambitious plan aimed at proving that “Women pilots are as capable as men.” “Girl Plans Solo Paris Hop as Shopping Trip,” the Brooklyn Daily Eagle trumpeted, detailing Minners’ hopes of becoming the first woman to make a trans-Atlantic solo flight. (Another rising aviation star, Amelia Earhart, would beat her to the feat a few months later, leading Minners to abandon the gambit.)

Unbowed, however, Minners continued jumping at every chance to defy stereotypes and expectations. In the process, she gained a national following that led to a kind of perverse success: At the peak of her notoriety, she became a much publicized shill for Camel cigarettes. “Camels don’t jangle my nerves,” she purportedly said in one widely circulated ad that touted her parachuting prowess, “and they encourage good digestion in a pleasant way.” (“She really wasn’t that much of a smoker,” Carol Williams remarks. “It was a bunch of hooey.”)

“She was just always different from everybody else,” Williams recalls as she pages through her mother’s voluminous scrapbooks — noting that Minners, a bona fide phenomenon in her early years, spent most of her latter decades beset by mental illness and fading into relative obscurity.

Minners retired from her high-flying, news-splashing adventures around 1940, and after a stint working as a clerk for the Defense Department, she lived in various places around the country before settling back in Hendersonville. There, she taught children’s evangelism courses, among other pursuits. Minners died in 1997 at age 88, and she’s buried in Oakdale Cemetery, where her headstone displays an etching of a biplane soaring through the clouds above the word “Grounded.”

The article is an interesting bit of history about an unconventional woman. One can wonder how many tattoos she had, if any. Hmmm…. no internet, cell phones, television, or even radio except in her later years. The adventurers had to do something unique.