By Kate Martin, originally published by Carolina Public Press. Carolina Public Press is an independent, in-depth and investigative nonprofit news service for North Carolina.

As the coronavirus took hold throughout the country and many office jobs shifted from in-person to remote work, a mainstay of civic action also made the switch.

Despite the pandemic, state and local governments must still follow North Carolina’s open meetings law. Enshrined in state statutes in 1971, the law says governments and their committees must conduct their business in the open, where the public can see them.

But since the pandemic struck in March, those looking to stay informed of what their governments were doing have often either been locked out of virtual meetings or met with technological flubs.

Brooks Fuller, the director of the N.C. Open Government Coalition, said most problems are likely unintended. But whether accidental or deliberate, the effect is the same. Technology problems lock the public out of important business.

“It sounds like a lot of the problems citizens have had with meetings during the COVID era are having to rely on inferior technology or technology that’s being mismanaged,” Fuller said. “That has been a pretty resounding theme.”

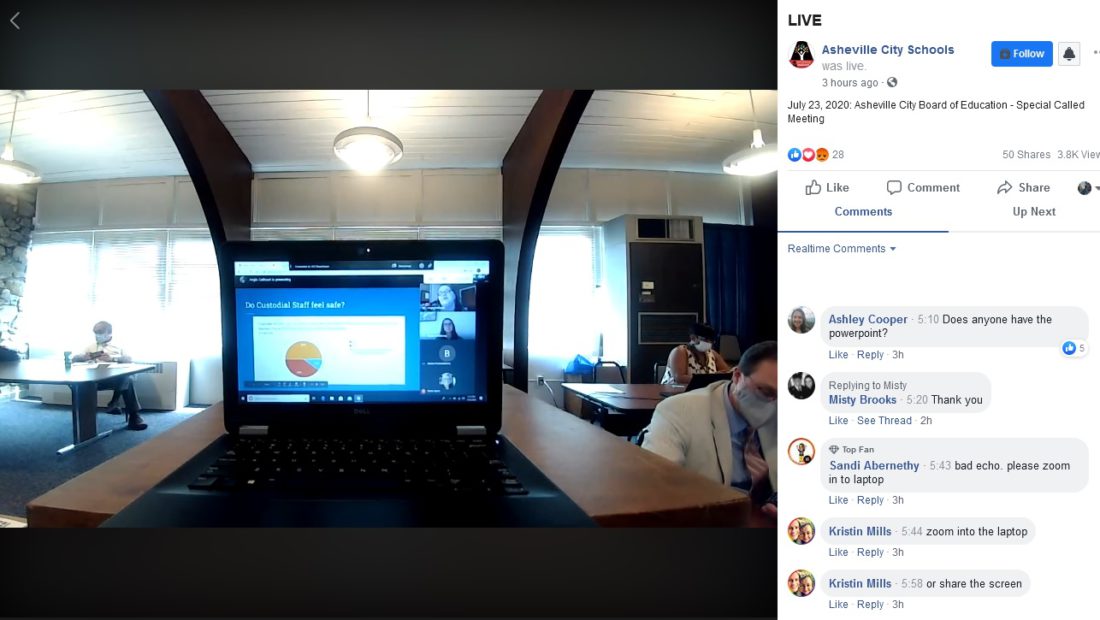

Last month, the Asheville City Schools board was trying to decide whether to start the year with in-person or remote instruction. During the meeting that the district streamed live over Facebook, reverberating audio, a wildly swinging camera and a video feed that cut out at several points made the meeting difficult to follow.

Carolina Public Press and Asheville-based Mountain Xpress have filed a complaint with the school district, asking it to improve its virtual meeting practices. The district has so far not responded to the complaint, filed Aug. 3.

Fuller said that early in the pandemic, he was getting calls each day about meeting irregularities and open government violations.

“Early on, there was a lot of free-flowing discussion and a real lack of consistency,” Fuller said.

“A school board in one county might be operating under a different set of rules than a city council in a town. They are not required to use the same platform or have the same accessibility issues in mind — but they ought to.”

One example Fuller cited was governments tacking on closed meetings before or after the public version. Those meetings must be announced in open session, and the boards must take a vote to close the meeting for an expressed reason, not just put “closed session” on a preprinted agenda.

“It may not be malevolent, but it doesn’t meet the standards of the open meetings law,” Fuller said.

In early May, the UNC School of Government posted standards for remote public meetings and accessibility.

Those standards say members of deliberative bodies — like a school board or city council — must identify themselves at the start of the meeting, prior to participating in deliberations, when making amendments or motions, and before taking a vote. These actions did not occur during Asheville’s school board meeting, for example.

While public bodies previously had to hold meetings in a place where the public could attend, advance notice of remote meetings must include instructions on how the public can log in to view the deliberations — which must be aired live.

There is no statewide standard on how public officials must learn about the state’s open meetings laws. So Fuller sends a politely worded letter to governments whose practices could use a nudge toward the law.

He sent one such letter to Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools in April and noted several areas for improvement.

About a week and a half later, school board Chairwoman Mary Ann Wolf replied, saying the district would make changes to the remote meeting procedures. Those changes included making clear when the meeting began and when closed sessions ended, and having a personnel agenda posted before the meeting so residents could follow along.

Fuller said the Chapel Hill-Carrboro school district is the only government “that has engaged in a dialogue with me.”

Others, like the Dare County Control Group — which sets policy for the county’s department of emergency management — did not reply to Fuller’s May letter asking for legible copies of meeting minutes.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.