Mallory McDuff can’t escape nature — and she has no intention of doing so. In fact, it’s her goal not to.

A member of the Environmental Studies and Outdoor Leadership departments at Warren Wilson College, McDuff’s primary role is teaching environmental education. A native of Fairhope, Ala., she lives on campus in a 900-square-foot rental with an expansive view of the mountains. Meanwhile, the college’s cattle and sheep graze in the pastures right in front of her house.

“The crazy thing is I’ve been here for 23 years, so I’ve been teaching here longer than most of my students have been alive at this point,” she says.

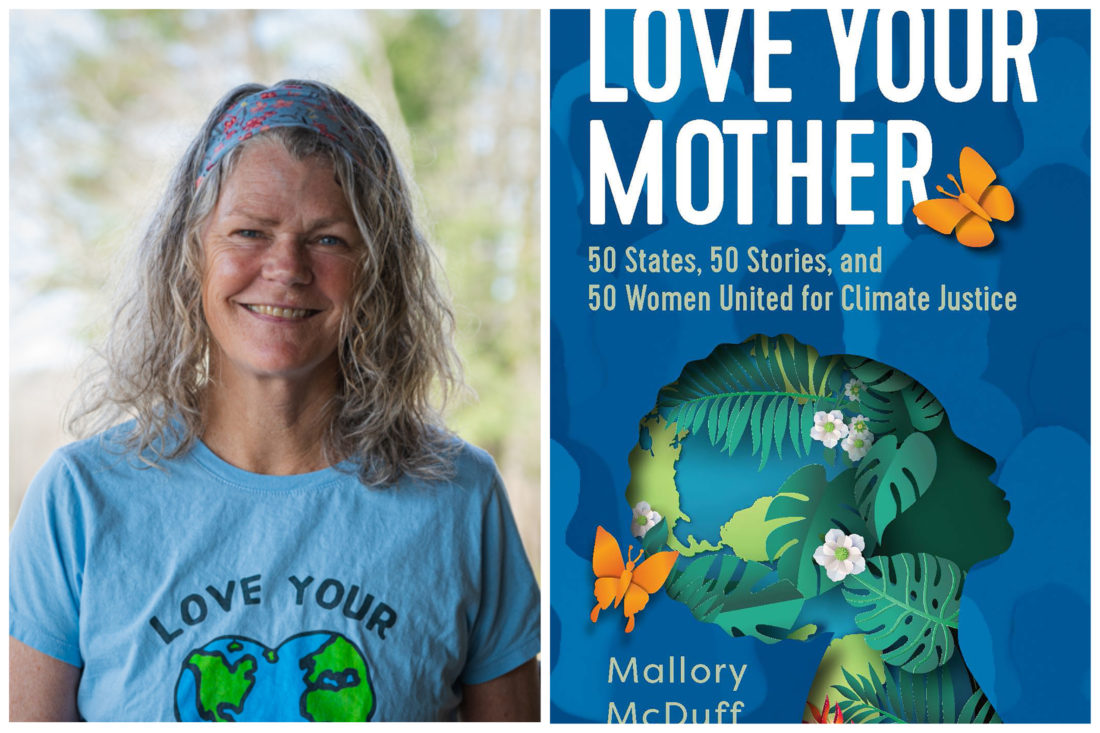

Alongside teaching, McDuff’s written five books. Her latest, Love Your Mother: 50 States, 50 Stories, and 50 Women United for Climate Justice, is slated for release on Tuesday, April 11. Geared to inspire readers to use their unique strengths in their environmental activism, the work provides numerous inroads for people of all backgrounds to take part in what many consider the greatest struggle of our time.

A friend indeed

Following the 2021 publication of her green burial book, Our Last Best Act: Planning for the End of Our Lives to Protect the People and Places We Love, McDuff sought a new focus within the wide world of environmentalism.

“I was really interested in how to tell stories — short, succinct stories from across the country that would provide some great inspiration but also some ways to engage,” she says. “I didn’t want to tell stories of one individual and what they did by themselves, but rather stories of people who are engaging in their communities and creating collective action.”

McDuff also wanted to present a range of disciplines to better serve her diverse student body. For example, she says, if an art major picked up the book, the student could read and potentially connect with Jess Benjamin, a Nebraska-based ceramic artist who’s using her creations to educate people about drought and climate.

However, the true seeds for Love Your Mother were sown more than a decade earlier at an event that McDuff recalls in the book’s introduction. In either 2009 or 2010 — the author reveals in the text that she’s not entirely sure — she and her friend Jill Drzewiecki brought their daughters, ranging in age from 4-11, to protest the proposed construction of a new coal-fired power plant in Western North Carolina.

“It’s kind of a comical scene where [our daughters are] shouting, ‘No more cold! No more cold!’ because it was freezing. And what people were really shouting was, ‘No more coal!’” McDuff remembers with a chuckle. “It was an example of how you can enter into the climate space being who you are. For us, it was as moms and environmental educators but really as people who just wanted to engage how we could — to use not new skills that were out of our wheelhouse but what we brought as mothers and as educators.”

At the time, Drzewiecki was a fellow Warren Wilson faculty member. Today, she serves as a gender-responsive education specialist for Jesuit Refugee Services in Rome. In 2019, McDuff visited her friend overseas. While there, she and Drzewiecki had a conversation that the author says she’ll never forget.

“I had a couple of different ideas [for my next book], and [Drzewiecki] said, ‘I see so many women in refugee camps and in our everyday lives — there’s so much to do and so many are overwhelmed just with the logistics of life, particularly in a climate crisis. Think about lifting up stories of women across the country,’” McDuff says.

The combination of those motivations convinced McDuff that she had the foundation for a compelling book, and she quickly got to work.

50 ways to choose a subject

Drzewiecki was also the person who provided McDuff with the framework for Love Your Mother. The author considered featuring 100 women (too ambitious, she recalls) or 25 (insufficient) but her friend suggested choosing one from each U.S. state. Solidifying that approach was a desire to spotlight underseen communities, including environmental work in her native state.

“When I went to college and went away to Peace Corps, most people didn’t even know Alabama had a coastline,” McDuff says. “I wanted to show that there are climate leaders in every single part of the country — rural, urban, suburban.” People of color, she adds, account for half the participants. “I really wanted to show a diversity of stories and vocations.”

McDuff says she began her research by “casting a wide net” and touching base with a range of connections in the climate movement and asking for recommendations on whom she should interview. Among these connectors was former Asheville-based filmmaker and activist Dayna Reggero, who put McDuff in touch with several women, including Tiffany Bellfield-El-Amin, a Black farmer, restaurant owner and birth doula in Kentucky.

“I knew I wanted to have farmers; I wanted scientists; I wanted educators,” McDuff says. “These women were so inspirational, and I left really feeling like I had these collaborators and friends. And that was really motivating to keep going.”

McDuff also felt it was important to feature several famous figures, including poet Amanda Gorman and Varshini Prakash, executive director of the Sunrise Movement. Though none of these sources were available to speak with her for the book, McDuff dedicated sections to each with help from secondary sources.

“One thing that was really important to me was to have a balance of women who are well known in the climate space, and then women who are just well known in their communities,” McDuff says. “For my students — and for me, honestly — it can be a little intimidating if you think you’ve got to be this dynamic climate activist who does Instagram Lives all the time and is so captivating. So, I wanted there to be stories of people that are living their lives, but they’re integrating climate into their life.”

Further aiding that accessibility is a unified structure. Each woman’s story begins in the middle, looks back on the past and then forward to her future — all in the course of three pages.

No time to lose

Consistent with her aim of inspiring attainable change, McDuff ends Love Your Mother with the chapter “50 Ways to Love Your Mother,” featuring a recommended action step — summed up in a single sentence apiece — that people in each state can take.

While these opportunities will likely be new to most readers, McDuff didn’t wait to share them or tales of her interviews with her students. Fond of name-dropping famous climate activists and Warren Wilson alums alike to help inspire her undergrads, McDuff made sure to keep her classes informed of her progress with the book and pass on the lessons she learned in a timely manner.

“These women know how to work together, and working with others is the only way that we’re going to generate momentum,” McDuff says. “The structural obstacles include the fossil fuel industry, government subsidies, racism, capitalism and white supremacy. These are big, big structural obstacles. But what I learned from each of these women is that they don’t think the story is over yet. And neither do I. This is a love story, and the love story isn’t over yet.”

interesting how some people are able to make lots of profits from the biggest HOAX on the planet…