In the fall of 2019, the city of Asheville unveiled a proposal to secure the future of the century-old Thomas Wolfe cabin in East Asheville’s Azalea Park.

The ambitious plan called for restoring the dilapidated log structure, where the legendary author spent the summer of 1937, and transforming it into a writers retreat. Other ideas included developing the roughly 40 acres surrounding the cabin by adding a pavilion and public restrooms, creating trails and building new housing for visiting writers.

Officials were set to present the proposal to the Recreation Board and the Indiana-based Thomas Wolfe Society in the first half of 2020 and perhaps make a funding request. But then COVID-19 restrictions hit, disrupting those plans. Things were further derailed when project manager Stacy Merten retired from the city’s Planning and Urban Design Department in March 2022.

Now, some wonder whether plans for the site will ever get back on track.

“Every winter that goes by, it’s less feasible that the cabin can be saved, quite honestly,” says local author Terry Roberts, who served on the committee that oversaw the master planning process. “The thing that terrifies people like me is that somebody will go out there and have a party one night on the porch and light up a fire and burn the place down. It’s a miracle it hasn’t happened yet.”

City officials acknowledge that the plan has languished for nearly four years but are hopeful some progress can be made by the end of 2023.

“It’s such a beautiful place, and I think there’s a lot of different ways of looking at how people might want to enjoy it,” says Alex Cole, the city’s historic preservation manager. “I love the idea of focusing on writing, but I also think that it might be more helpful to cast a wider net for how the site could be used, as far as the reality of getting the funding needed for the improvements that are called for in the plan.”

A retreat of one’s own

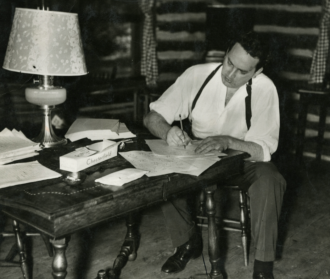

In the summer of 1937, Thomas Wolfe came home again.

Eight years after Look Homeward, Angel made him a literary star, the Asheville native wanted to get out of New York and hole up somewhere to write. Wolfe thought his hometown would be just the place, notes Roberts.

“He was alienated from a lot of people in Asheville who thought they recognized themselves or their relatives in the characters in Look Homeward, Angel,” he says. “Turns out, Asheville welcomed him with open arms. And, in fact, so open were the arms that he had to get out of town to find some peace and quiet.”

Looking for a place to rent, Wolfe turned to Max Whitson, a childhood friend and former classmate at UNC Chapel Hill. Whitson had built the secluded, rustic, two-room cabin around 1924 on his family’s property on a bluff near Oteen. At the time, the cabin sat about 5 miles outside Asheville, but it’s now within the city limits and far less secluded than in Wolfe’s day.

That summer, the author revised “The Party at Jack’s,” which was posthumously published as a novella in 1939 and as part of the novel You Can’t Go Home Again in 1940. Wolfe died of tuberculosis in 1938.

“The cabin represents a piece of Wolfe’s life that’s directly connected to Asheville and Western North Carolina that people just don’t know about,” continues Roberts. “The Wolfeans know about it and keep up with it, but as a general rule, even people who’ve read Wolfe don’t know about the visit back.”

Ambitious vision

But the cabin is worth preserving for reasons beyond its connection to Wolfe, says Jennifer Cathey, architectural historian and restoration specialist with the State Historic Preservation Office.

“It is a 1920s rustic round-log cabin, which is really iconic to the mountain region,” she explains. “And it’s on a pretty great piece of property that has scenic qualities and recreational value. You have a community asset that is worth investing in and preserving and using.”

Over the years, some additions were tacked on, and the cabin gradually fell into disrepair. The city designated the structure as a local historic landmark in 1983 and bought both it and the surrounding acreage from John Moyer in 2001.

Apart from stabilizing the roof and sealing the cabin, however, nothing further has been done to preserve it. There was an arrangement with the Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County to monitor the property, but it has lapsed, meaning no one is regularly checking on the site.

“One of my biggest concerns is that the master plan identifies several items that need immediate attention in terms of repairs,” says Jessie Landl, the nonprofit’s executive director. “Those things have not been addressed.”

The master planning process began in 2018 with the selection of consultant Lord Aeck Sargent, an Atlanta-based architecture and design firm. Literary scholars, preservationists, community activists, commercial entities and city representatives were involved in the effort.

After a public meeting in 2019, the firm released a master plan that envisioned a multiphase process designed to “return the immediate setting of the cabin to the time when Thomas Wolfe stayed in 1937, while allowing the remainder of the site to satisfy the needs of new programming.”

At the time, it was estimated that rehabilitating the cabin would cost $429,518, and fully funding the plan would cost anywhere from $3.5 million to $9.8 million, depending on a variety of factors. The consultant recommended that the Planning Department request phase 1 funding in 2020. Income generated by tours, retreats, merchandising and other strategies could offset some of those expenses, the plan suggested.

Shifting priorities

Cole, the city’s historic preservation specialist, became the point person on the project after Merten retired. She says the master plan has been on hold while her office focused on completing two architectural surveys and working to get the Walton Street Park and pool designated as local historic landmarks. Now that much of that work has been done, she hopes the cabin will once again become a priority.

A key step, notes Cole, will be reviving a subcommittee of the Historic Resources Commission that identifies candidates for local historic landmark designation and helps prioritize preservation efforts. Due to COVID-19 shutdowns and Cole’s own workload, the group has been dormant for several years, but she hopes it will become active again within the next six months.

“Their first order of business will be to map out their list of things they need to work on and prioritize that list,” says Cole. “I don’t know what that will look like yet, but I think [the cabin] will probably be high on everyone’s list.” She cautions, however, that other important projects, such as an architectural survey of Asheville’s historically Black neighborhoods, are still ongoing.

Once the subcommittee is reactivated, it will most likely work with the Preservation Society to try to get the Wolfe project back on track. That might entail things like forming a designated group that could focus on the cabin and updating the cost estimates, which are now 4 years old.

“I think, especially, the cabin restoration estimate would be critical for us to know at this point, because I have a feeling that’s probably where everybody’s going to want to spend the most energy fundraising,” says Cole. “Stabilization and restoration of the cabin are top of mind, because without those things, it loses the historic significance.”

What’s next?

Because of the master plan’s substantial price tag, working with private and nonprofit community partners will be key, she says. One possibility, notes Cole, is Asheville Unpaved, an initiative led by local nonprofits including Asheville on Bikes that seeks to build a network of multiuse trails throughout the city. The group has identified the Wolfe cabin site as a place to extend an existing trail.

But Landl of the Preservation Society wonders whether the $9 million proposal might simply be too ambitious for Asheville. “The fact that the city hasn’t moved forward with it leads me to believe that there’s some reasoning behind that,” she points out. “And so if they’ve determined in some way that that’s not the right direction, let’s find a nonprofit that could use that as their facility.”

She points to the recently announced Wilma Dykeman Writer-in-Residence program, a collaboration between UNC Asheville and the nonprofit Wilma Dykeman Legacy. The program provides a stipend and four weeks at the acclaimed author’s former home, a 1926 structure in Beaverdam. The Buncombe County native’s books chronicled the people and land of Appalachia.

“They really did something very similar, where they took a historic site and turned it into a writers retreat,” says Landl. “I think it’s interesting that there’s sort of a model for it in town.”

Thank you to Mr. McGuire for bringing us up to date on this project which has faded from public consciousness. Ms. Landl’s conclusion that a $9 million cost is too high for Asheville is no doubt realistic. And her mention of the Wilma Dykeman writer’s residency suggests that Asheville may not need another place for a writer to retreat, especially with that price tag.

The continuation of this project is so worthwhile. Asheville has a long history of being a center of writers and Thomas Wolfe is certainly among the most revered. Asheville also has an economy based on tourism and restoration of the Wolfe cabin is an important contributor to sights that bring tourism and writers. We should not allow yet another piece of our history to be lost simply to neglect or a masterplan interrupted by a pandemic. Let’s save our history and create a writer’s center that will bolster the regions literary importance. We can’t be all about beer.