Amid the flood of new books marking the Civil War’s 150th anniversary, one tells a uniquely North Carolinian story — that of a desperate prison break in the Piedmont and a flight through the state’s mountains, where neighbors sometimes fought neighbors with the fury of rival armies.

In Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy: A Civil War Odyssey, reporter and historian Peter Carlson revisits the sometimes rollicking and often harrowing saga of two journalists who went to record the war firsthand and wound up in Confederate custody, becoming a story in their own right.

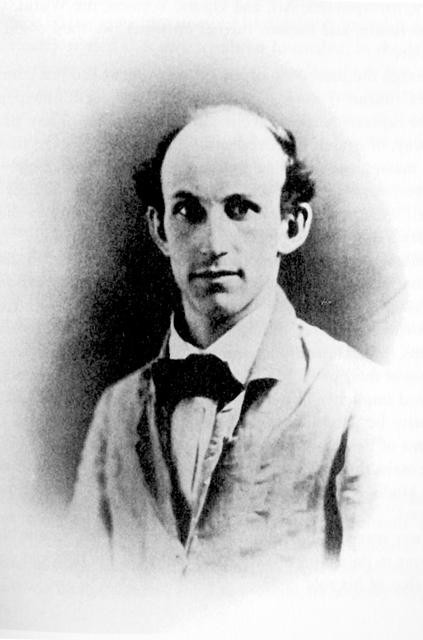

Junius Browne and Albert Richardson were friends who landed jobs at the New York Tribune, a leading Northern newspaper that circulated throughout the United States. The paper was staunchly abolitionist, owing to the convictions of its famed editor, Horace Greeley, who sent the correspondents south to cover the conflict’s ever-fluctuating fronts.

The pair resolved to do so with aplomb, joining a self-described “Bohemian Brigade” of Northern correspondents who threw caution to the wind. The loose-knit but like-minded group had a “semi-serious code,” Carlson notes. They “would suffer all necessary privations without grumbling, laugh at danger, and try to extract as much fun as possible out of the grim business of war.”

Browne and Richardson certainly found adventure, if not exactly the sort they sought. March of 1863 found the two reporters, both 29 at the time, on the margins of the Battle of Vicksburg. That Mississippi clash would end in a Union victory and help turn the tide of the war, but by the time it unfolded, Browne and Richardson had been captured by rebel troops. They weren’t soldiers, but they were sent off to prison amid calls that they be lynched.

And though the reporters had already spent years filing dispatches of heroism and tragedy on the battlefield, their personal struggles had only just begun. Their efforts to be exchanged in a noncombatant prisoner swap were stymied time and again as they were shuttled to prisons in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Virginia. They landed in a hellhole of a penitentiary in Salisbury, N.C., in what might have proved their final destination.

In Salisbury, as the war’s human costs multiplied and the prison population swelled, the pair came to know Civil War POW life in all of its misery, even as their status as journalist prisoners spared them some of the worst of it. Overcrowding, disease and near-starvation were constant companions, the stench of filth and death ever in the air.

Their spirits flagging after a year and a half in captivity, the journalists committed to a madcap plan to win their freedom. They’d sneak out of the prison and make their way west through enemy territory until they reached the Union lines in Knoxville, Tenn.

Without giving too much away, the story of that flight is one of the most captivating parts of the book, in part because it examines just how divided the state’s residents were over the war — and just how far they’d go to demonstrate their loyalty to either the United States or the secessionists.

A secret society of Tar Heel Union supporters aided the escape, as did the journalists’ true saviors: sympathetic slaves who hid the Northerners during their initial terrifying nights on the run. “Every black face was a friendly face,” Richardson later recalled. “They were always ready to help anybody opposed to the rebels.” White faces were harder to read, but eventually it was a cadre of white, pro-Yankee mountain folk who spirited Browne and Anderson through Western North Carolina, against great odds.

Carlson adds rich context to this cliffhanger through descriptions of the secondary but important characters — the worried families back home, the fellow journalists caught in the conflict, the power-mad wardens, the wretched prisoners, the profiteers and spies, and the host of unlikely heroes from all walks of life.

Revisiting old territory with a new view of contemporaneous sources, he’s used Browne and Richardson’s story to open a window into how the Civil War ruptured the fabric of American politics and history, sparing almost no one, including a couple of brash young journalists.

His book is rife with reminders of why stories of the war, first forged by partisan reporters, remain as contested today as they did when the Bohemian Brigade joined the struggle.

who: Peter Carlson, reading and signing for Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy

where: Malaprop’s

when: Saturday, June 8 (7 p.m., free. www.malaprops.com)

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.