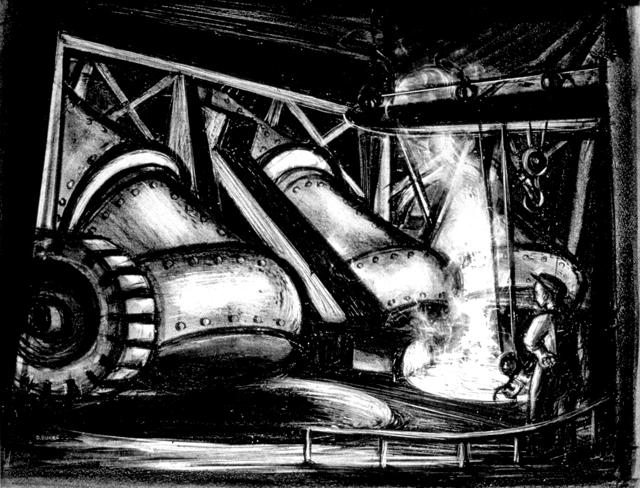

- Everyone was contributing in their own way: David Burke’s “Copper Smelters,” (1935, lithograph) is part of a show celebrating work from the Great Depression era. Images courtesy Asheville Art Museum

- “Squid Under Pier,” Manna Citron, 1948-49, Intaglio-stencil print.

Although the exhibit draws from the economic devastation and social despair of the Great Depression, Artists at Work: American Printmakers and the WPA, at the Asheville Art Museum through Sept. 25, is surprisingly joyous. Many associate the Works Progress Administration with road construction, bridge building and land conservation projects, but one WPA unit, the Federal Art Project, acknowledged that artists were also workers who needed jobs.

“This is a show about the accomplishments of a culture, one where everyone was contributing in their own way,” says Cole Hendrix, the exhibition's curator.

While some 2,500 murals and almost 18,000 sculptures were created for public buildings under the Federal Art Project, Hendrix has narrowed her focus to a sampling of the printmakers who made an estimated 200,000 prints. The exhibition is a celebration of the variety of the artists’ techniques, styles and imagery. It also celebrates what can be done when the government decides it's time to put people back to work.

When we think of the Great Depression, images of destitute men and women standing in bread lines, union protesters and the rural poor within gray, barren landscapes come to mind. Such images are all here, in the representational social-realistic style we associate with the period: urban masses set against the dehumanizing city; workers set against the forces of industrialism; rural laborers set against the forces of nature. But mixed in are darker psychological portraits of men beside women, of highly abstracted figures and landscapes of European Modernism and hints of the Abstract Expressionism that would follow Social Realism.

Copper Smelters, a lithograph by David Burke, lets loose an industrial landscape filled with fearsome machinery liquefying metal. A figure in the foreground is dwarfed by three immense cylindrical metallic beasts. Sharply outlined and streaked with gray, the machinery is alive with motion, even as the human worker is stationary. A cloud of steam makes this image feel as hot as the attendant nearby must have been.

Man and His Monuments, a 1935 lithograph by Carlos Anderson, is more typical of the glory that WPA prints often bestowed on construction and development. This print gives a reverent view of Manhattan’s newly constructed Rockefeller Center. Anderson’s print suggests that the privately funded Rockefeller building is the new way, as the new monument. The Art Deco skyscraper glows; its fuzzy white edges radiate light around the intense blacks on the building’s north-facing walls. Smaller gray buildings surround the structure, while the sidewalk bustles with minuscule people passing by a gothic church.

Leon Bibel’s Unemployed Marchers, a 1938 lithograph, and Paul Meltsner’s Death of a Striker, a 1935 lithograph, illustrate the social protests we often connect with Depression-era life and art. Here the protesters are larger-than-life heroic figures, as muscular as Hercules.

Two African-American artists, Dox Thrash and Sargent Claude Johnson, and a Japanese-American woman, Miné Okubo, among others, reflect the diversity of the Federal Art Project at a time when even nods at racial and gender equality were rare in American culture. Thrash, one of the developers of carborundum printing in 1937, the first new printmaking technique in 100 years, worked in the prevailing figurative style. In Defense Worker, from 1941, another Herculean figure towers over what looks to be a riveter or jackhammer. The majesty of this African-American man diminishes the tool’s heft to that of a shovel. His heroic pose makes its own quiet assessment of the social landscape.

Johnson and Okubo mark the exhibition’s transition from the Social Realism of the early ‘30s into Modernism and abstraction. In Johnson's 1938 Lenox Avenue, a solemn face has been dissected in a surrealist fashion similar to Joan Miro’s prints. Minimal shading pairs with simple linear patterns and abstract marks to flatten the most basic facial features into geometric planes. A small piano keyboard references the concurrent Harlem Renaissance and the rise of jazz in New York City.

Okubo’s 1935 print, simply titled Abstraction, is one of the show’s few silk screens. Her piece breaks away from the group by using a lemon yellow as a backdrop for a faintly depicted human form and a blueish saxophone. Squid Under Pier, a 1948 intaglio-stencil print by Minna Citron, delves even further into Modernism by reducing her background to a series of earthen brown and blue geometric shapes representing the pier and the sky. Black curvilinear swirls become tentacles and join a single visible eye to form the beast.

The show diverges from Modernism and abstraction to finish with works that return to relatively realistic, but still highly stylized construction and development landscapes. Pittsburgh, a color lithograph by Elizabeth Olds, portrays the river and the rush of the railroad yard in a semi-expressionistic style. Sharp edges form mounds of a mysterious product in one corner while boldly outlined clouds pour from an army of smokestacks in the distance. The show exits the city and ends in a subdued rural atmosphere — one that includes views of tobacco trade in a massive warehouse, a bridge and work around the house.

Job security and the consistency of projects and pay “enabled [artists] to experiment with new techniques and styles,” according to Hendrix. Thrash and his fellow printers had the freedom to explore and create new printing techniques in their Philadelphia workshop while Okubo and others took screen printing away from commercial production and brought it back to the realm of fine art. “The assurance of a steady paycheck freed artists from the constraints of working to please the tastes of private patrons.” Lithographers began using color and woodcut printers began to utilize and rehash expressionist techniques in combination with current designs while others turned directly to pure abstraction.

Artists at Work: American Printmakers and the WPA draws largely from the museum’s collection of WPA prints bequeathed in 1993 by Thelma “Teddi” Lowenstein. A former Asheville resident, Lowenstein and her husband, who worked as a printmaker for the WPA, were area artists. Among printmakers, it’s common for artists to trade prints from their editions, so Lowenstein's collection was especially rich. According to Frank Thomson, head curator at the Asheville Art Museum, the collection of roughly 30 prints had been stowed away in her closet before it was donated.

During the three years that Hendrix was researching the show, she found she needed to fill gaps, especially to represent the works of women, African-Americans and the more abstract works created in the latter part of the Federal Art Project. The museum's Collectors’ Circle purchased four new prints recommended by Hendrix, and she was able to borrow other exemplary works from other institutions.

Artists at Work is an example of a how a museum can build a show from the strengths of its own collection — and how a specific show can help its collection become even stronger. Museums across the country are turning to their permanent collections to help save on the costs of high-dollar artwork loans from other institutions. The Museum of Modern Art in New York, for example, recently rearranged its galleries to focus on work from its own collection.

With our own Great Recession resembling more and more the Great Depression, Artists at Work has lessons on how good art and good exhibitions get made in hard times. We must revel in a show of this nature. It’s a celebration of the past and the present, of people, and of printmaking.

— Kyle Sherard is an Asheville printmaker, painter and writer for the arts.

Some pictures to go with this nice review would be helpful.

I see the lack of pictures was only on the new (but not improved) website. The “old” website has two nice images. Old website is much cleaner and easier to navigate. New website is cluttered and confusing. “New Coke” sometimes has to go away and return to “Classic Coke.”