I had every intention of starting off the New Year with a round up of readings, books releases and other literary-type activities. Two different events foiled that plan: First, local readings and releases, this time of year, are few and far between (go to Malaprop’s for some likely bets). Secondly, a not-to-be-passed-up book landed on my desk.

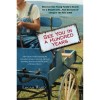

See You In A Hundred Years (Delta) by Logan Ward—out in paperback this month—is the perfect read for long winter days and dark, chilly evenings. It’s a memoir, but also an adventure. And, though the book leans heavily on post-September 11 lessons (it takes place during 2001 and 2002), today’s recession renders Ward’s story quite timely.

Years recounts the four seasons Ward spent in rural Virginia during which he and his wife, Heather, attempted to recreate a 1900 farming life, down to the wood cookstove, the root cellar and the outhouse.

“If I take anything away from our 1900 experience, it is a newfound appreciation for the miracle of the seed,” Ward writes near the end of his book. “Heather and I have proven that a rubber-band-bound clump of seed-filled envelopes can feed a family of three for a year.” The husband and wife were both raised in small, Southern towns but had lived for a decade in New York City. A number of small, niggling concerns had Ward thinking of the simpler life, but it was when he witnesses a 12 year-old at the Brooklyn Zoo unable to identify a cow that he decided his own toddler son would not grow up so removed from the land.

Of course, moving to the country and moving back in time to a pre-eletricity, pre-automobile existence are two entirely different journeys. Fans of PBS series such as Frontier House and The 1900 House have some idea just how difficult it is for a family used to modern conveniences to learn to live as our ancestors of a century ago. What seems at first a fun jaunt back to a simpler time becomes a complex obstacle course of manual labor, hardships and being at the mercy of the elements.

In fact, for Ward, even getting to 1900 was a challenge. “Not only are we stressing ourselves out in order to de-stress, we’re rushing to slow down, re-creating the past with the aid of modern technology, and replacing our stuff with heaps of period-appropriate stuff (so much for Thoreauvian asceticism),” he writes in the beginning of his memoir.

Rules are made: The family keeps their car for emergencies but parks it in a field (where it’s subsequently eaten by rodents); they keep their phone line (also for emergencies) but unplug the phone and refuse to even borrow neighbors’ cell phones. They decide against period costume, though bikini underwear and wool-blend socks (the non-itchy variety) are considered contraband. The reader has to wonder why at times: Isn’t it enough that they pump their water from a well, bathe in a livestock trough and use a horse-drawn cart for transportation? Is it really necessary to forgo tampons and disposable razors?

On the other hand, Ward’s wife—a vegetarian—sticks to her meat-eschewing menu though it’s unlikely a farm family at the turn of last century would have even heard of a plant-based diet. There is precedence for circa 1900 vegetarianism, but it was hardly the rule of the day.

To the reader, it ultimately matters little how accurately the Wards recreate the year 1900. The premise lends itself to an interesting plot, but this story is more about what the family learns about themselves and the community they encounter through their experiment. Not quite half-way into their year, the September 11 terrorist attacks bring them much fodder for introspection.

“…now the so-called forces of evil have attacked the U.S., felling the twin symbols of American economic might,” Ward writes. “For the first time, our project feels practical, in the most distressing of ways.”

And later, “As the neighbors bring news of war in Afghanistan and anthrax scares … I realize how lucky we are to be be here together on these peaceful forty acres.”

As I mentioned at the start of this review, the book strikes a parallel with the current economic crisis, as well. Americans are being forced to cut back, to rethink values of consumerism as ask themselves if—should the need arise—they could live off the land. Years calls to mind WWII-era England, when city-dwellers were asked to “plant a garden for victory,” offsetting food rations with home-grown produce. Though the Ward family doesn’t need to subsistence farm (they had good jobs in New York, they have supportive families, there are plenty of well-stocked grocery stores) their year in Virginia teaches them that they can do it. With little prior knowledge, they successfully plant a garden, preserve food, tend livestock, make goat cheese and cook three meals a day on a wood-burning stove (heated, of course, by wood they chop).

But these triumphs seems to pale against more personal realizations. In the end, it’s the small things that hold the most meaning. “At first, my father, who would be lost without his cell phone, could hardly imagine surviving a year without calling us,” Ward writes. “But he has come around. He writes often, and I get more substance and sincerity from one of his letters than a dozen distracted phone chats.”

Years is thoughtful, well-written and often humorous. It comes to a fruitful culmination, yet ends all too soon. This is no slight of Ward’s skill as a memoirist, but rather a comment on how successfully he pulls the reader in the 1900 world with all its trials and rewards.

—Alli Marshall, A&E reporter

What a beautifully written article by this reporter. Made me want to read the book, something a good review should do.

I recently finished reading Better Off, by Eric Brende, which recounts almost the the exact same experience by the author. It was a worthy read.

Your review gives the impression of Years to be equally inspiring and romantic. I look forward to reading it.