Last summer’s merger of Penguin and Random House formed “the world’s largest consumer book publisher,” according to Library Journal. The other publishers making up “the big five” (formerly “the big six” — that small pond keeps getting smaller) are Macmillan, Hachette, Simon & Schuster and HarperCollins.

Of those, only the last two are U.S.-owned.

Things are pretty weird in the book publishing world these days — it’s a scenario not unlike what the major-label music industry has witnessed in the past decade. And, like musicians, authors are increasingly eschewing the big five in favor of smaller imprints. Small publishing houses aren’t handing out million-dollar advances, but they do promise hands-on support and close working relationships between author and editor or publisher (who are often one and the same).

Small presses also offer diversity. Though most put out only a few titles a year, there are many boutique publishers to choose from, and they’re as varied as the authors they serve. “Gone are the days when The New York Times best-seller list provided readers all they needed to know about the best books to read,” says a press release from the Independent Publisher Book Awards, presented annually since 1996. “More than a million books are being published each year, and many of the nation’s top authors are realizing that in a fast-changing marketplace, independent publishing offers the flexibility required to succeed,” says the release. A significant number of those books are coming out of Western North Carolina’s small presses — some of which have been in business for decades, while others are just starting up.

Niche reads

Black Mountain Press founder Jack Moe says he feels connected to WNC’s rich tradition of art, literature and storytelling. That includes Horace Kephart’s Our Southern Highlanders, published in 1913, and Waynesville resident Caroline Miller, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1934 for Lamb in His Bosom (the first author from her native Georgia to win the fiction award).

“We look for writers who are also influenced by Asheville’s Thomas Wolfe, as his influence extends to the writings of famous Beat writer Jack Kerouac, and authors Ray Bradbury and Philip Roth, among others,” says Moe. “He was one of the first masters of autobiographical fiction, which we would like to print more of.”

Corina Heich, the newest editor at Black Mountain Press. Phot courtesy of the publishing house

Corina Heich, the newest editor at Black Mountain Press. Phot courtesy of the publishing house

Add The Carolina Mountains to that list of historical writings. Penned by Margaret Morley and first published in 1913, it combines travelogue, biological observation, history and photography. Fairview-based Bright Mountain Books, established in 1983, reprinted the tome in 2006.

Black Mountain Press was launched in 1994 to publish guides, usually for outdoor activities. “We had been designing books for other presses and realized there was an opportunity to publish books in this outdoor niche market,” says Moe. At the time, there were only a few other presses in WNC: Most Tar Heel publishers were in the eastern part of the state.

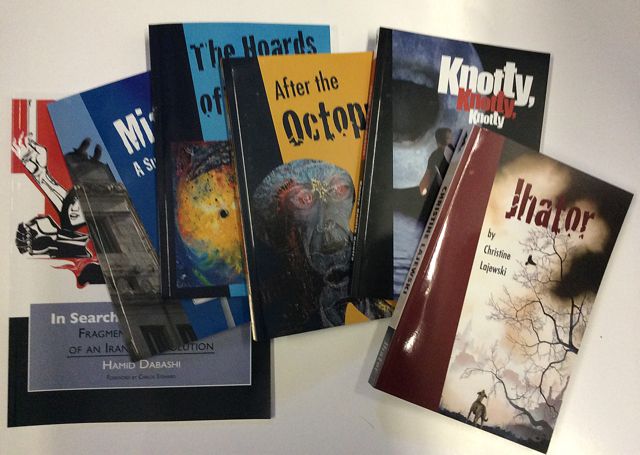

“The Black Mountain Press has gone from a niche outdoor market to a niche literary market,” says Moe. It now publishes mostly novels, plus some short-story collections, creative nonfiction and poetry. Memoirs, graphic novels and the occasional how-to book may also make the list. Simulcast Strategy, a 1996 manual for playing the horses, ranks among the publishing house’s best-sellers. Among Moe’s current favorites are The Reharkening, a book of poetry, and the dark novel Knotty, Knotty, Knotty.

“Our advantage is that we concentrate on the types of books most mainstream presses reject — books that are more artistic in language and written mostly by emerging unknown authors,” says Moe. “Small presses have been credited with keeping short stories alive, not to mention providing crucial life support for poetry.” While a trade publisher is likely to turn down a book that’s not going to sell tens of thousands copies, small presses will take on those books that seem important, even if the sales are likely to be incremental.

Luke Hankins is also looking for a publishing niche. The senior editor at Asheville Poetry Review and a published writer himself, Hankins is in the early stages of launching his own publishing house, Orison Books. The word “orison” means prayer (Shakespeare used it in Hamlet), and the press will focus on the connection between literary and spiritual writing from a non-ideological perspective. “We intend to publish poetry, fiction and nonfiction,” says Hankins. He’s open to anything of literary value, regardless of genre.

Hankins hopes to release Orison’s first title later this year, but that depends on his ability to raise the requisite funds. He needs about $45,000 for a successful launch, but he doesn’t initially require a storefront or office space, which cuts down on overhead.

“A few years ago, I wouldn’t have even considered print-on-demand, because a lot of the outlets were producing products that looked really shoddy,” says Hankins. “But the quality has improved dramatically. They can even do hardcover.”

Low cost, high reward

As print-on-demand services have improved, they’ve also decreased in cost — a one-two punch that’s opening the door to independent publishing imprints. A.D. Reed, an editor and ghostwriter, worked briefly in New York for the publisher of Webster’s New World Dictionary and as a freelancer. “It was always words,” he says. “But I envisioned myself as the nonbusiness-side creative type.” The affordability of desktop publishing (page layout software for personal computers) made a huge difference, because he no longer had to think in terms of massive quantities of books, or office and storage space.

Originally, Reed considered setting up a cooperative with several of the writers he worked with. They would pool resources and talents to get books out to the world. But when one of his projects needed a publishing company, Reed decided to launch Pisgah Press in Candler. The cost to incorporate, in 2011, was a mere $125. Then, Reed says, “People started coming to me and saying, ‘Would you be interested in publishing my book?’”

The biggest hurdle for any small publisher is marketing. National coverage in the form of reviews and TV talk show spots is expensive. “If you’re not in Publishers Weekly, you’re climbing Mount Everest, not Mount Pisgah,” says Reed. He’s currently in the process of his first major marketing push for a history book that’s due out in April.

Micki Cabaniss Eutsler, Michele Scheve and Lindy Gibson inside Grateful Steps Foundation’s Lexington Station store. Photo by Carrie Eidson

Micki Cabaniss Eutsler, Michele Scheve and Lindy Gibson inside Grateful Steps Foundation’s Lexington Station store. Photo by Carrie Eidson

Grateful Steps Foundation (a nonprofit publisher and bookseller with a storefront in downtown Asheville’s Lexington Station development) uses community-based fundraisers to offset costs. But there are also titles that sell well. “If we were a business that picks books that made money, we wouldn’t have picked Tonda and TK: Friends,” owner Micki Cabaniss Eutsler says of the children’s book by Mary Byrd and Stephanie Willard. It’s about a friendship between a cat and an orangutan. “But National Geographic picked it up, and it won’t stop selling.” Other Grateful Steps titles include The History of Medicine in Asheville by the late Dr. Irby Stephens; the children’s book My Days with Nell by Victoria Blake, set at Biltmore House during the tuberculosis era; and A Book of Bullies by Katherine Stanley, a high school student with a rare disorder. The latter volume sold out in two weeks.

So how does Grateful Steps, which celebrates its 10th anniversary in July, decide what to publish? “We pick books by whose turn it is,” says Eutsler. The company has a waiting list of at least 130 authors, and one new writer’s name comes up each month. If that person has a viable idea, it goes to press. And for would-be authors with questions, Eutsler is available for two hours on Saturdays, offering free advice. “I think it’s a service to the community,” she says.

Mission statement

Grateful Steps’ mission also includes working with writers who have disabilities and “helping people who would not otherwise have a voice,” says Eutsler. In a way, it’s in her genes: Her grandparents were newspaper publishers in Pennsylvania. “This is my own personal spiritual journey,” she says. “I have a lot of joy in the work, and I feel like I’m following a calling.” Eutsler opened the company on the day after she retired from medicine.

EarlyLight Books, based in Waynesville and incorporated in 2007, is also a second career of sorts for founder Dawn Cusick. “I worked in nonfiction how-to publishing for Asheville’s Lark Books for many years and took a science class at UNC Asheville and later Western Carolina University every semester,” she says. “I was also raising young children and doing volunteer work with various literacy projects in their classrooms. I started jotting down ideas for children’s science books about 15 years ago, and at some point there was enough substance in the list to consider moving forward with a press.” The publishing house currently releases five to eight titles per year and packages nature nonfiction books for other publishers.

“My favorite titles are the ones that are about to be published or are working their way through the development process,” says Cusick. “Animal Geometry is one of my current soon-to-be-published favorites, and a science series for younger readers that’s in the design process is also at the top of my favorites list.”

Dawn Cusick, publisher and founder of Early Light Books. Photo courtesy of the publishing house

Dawn Cusick, publisher and founder of Early Light Books. Photo courtesy of the publishing house

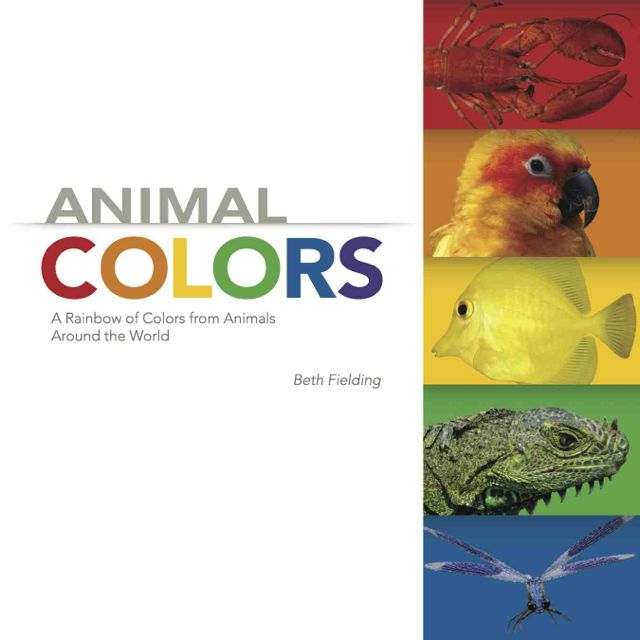

One of the company’s first books, Animal Colors, featured a white cover with a band of color blocks running down the far right side. A big publishing house probably wouldn’t have approved the design. “A former colleague was shocked when he saw it and said, ‘You’re not publishing a book about colors that’s almost all white,’” recalls Cusick. The printer, meanwhile, concerned that so much white on a children’s book would quickly become dirty, suggested a protective polymer coating. Problem solved.

Animal Colors is also published in bilingual (Cherokee/English) and monolingual (Cherokee only) editions, in collaboration with WCU’s Cherokee Language Program. “We were about to do a Spanish/English edition; the Cherokee editions just seemed like a logical extension,” says Cusick. “The Cherokee are very committed to their language revitalization program, and we may do more projects in the future.”

She adds: “The Cherokee books are a good reminder of one of the roles of small presses. We didn’t need profit-and-loss statements or marketing plans to get the idea approved — we only needed the right conversations to happen at the right time.”

A sense of place

Timing is important. So is flexibility. And, all those other reasons aside — a family history in publishing, a desire to represent unheard voices or to produce beautiful books — the malleability of independent publishing runs like a thread through the stories of various local presses. It’s a medium that’s open to an array of time frames, budgets and literary genres, and it isn’t site-specific. Consider the case of Ecco Qua Press.

The publishing house, whose name means “Here it is” in Italian, was started in Massachusetts. Owner Wendy Murray moved to Asheville last summer, and though the business is still registered in New England, she’s working to establish an Asheville identity as well. “I have a very simple business model. I can essentially set it up wherever I am,” she says. Already, Murray has spoken at one of Malaprop’s small-press events, where local publishers and authors discuss their work.

“I have some some good, solid writers from New England who we’ve published, and I’m proud of that heritage,” says Murray. But she also wants Ecco Qua to tap into the local literary tradition. Wolfe and Carl Sandburg, with their masterful use of language and metaphor, rank among the canon, she points out. “For independent presses, a regional identity is critical. That’s where you’re going to get your enthusiastic readers and your supportive community. Not to mention the reservoir of riches that comes out of a locality.”

East Asheville-based Logosophia Books, run by husband-and-wife team Stephen and Krys Crimi, got its start in agriculture. Sort of. The Crimis were living on Philosophy Farm, a biodynamic property in Mars Hill. A friend had collected the talks of the late master gardener Alan Chadwick and bequeathed them to Stephen, who transcribed the talks with the intention of making a book. A publisher was interested but couldn’t raise the funds for the project. Luckily, on-demand printing had become affordable, so Stephen decided to go that route and released it, his first book, in 2007. “It worked out pretty well. If you don’t count the year of work you put into it, you break even,” he jokes.

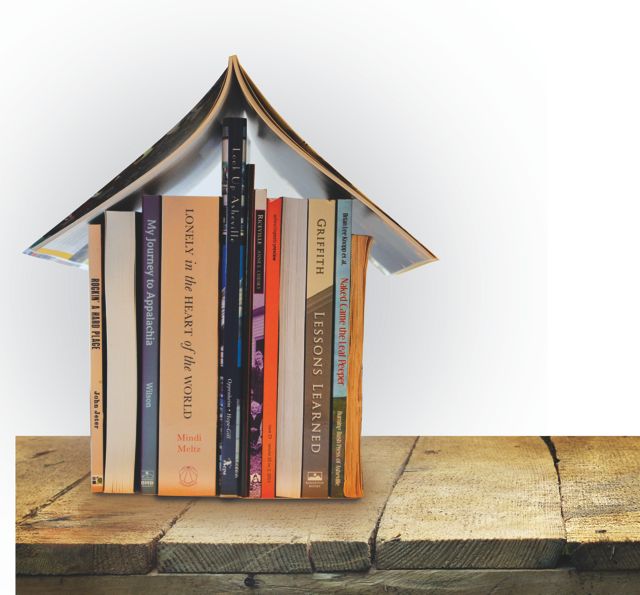

Initially, the idea was to use publishing as a verbal expression of the farm. But Stephen soon moved on to poetry, beginning with the work of local writer Tracey Schmidt. Last year, Logosophia made its first foray into fiction with Mindi Meltz’s Lonely in the Heart of the World.

By then, Stephen and Krys had moved off the farm. “We’re huge lovers of books,” says Stephen. “One of our main things is to produce the most beautiful books that we can.” Logosophia uses local artists such as Brian Mashburn, and Krys contributed calligraphy and illuminated lettering to Lonely.

Worthy words

Ultimately, small presses are labors of love. “I have a classical notion of beauty as an expression of the sacred,” says Stephen. “That’s kind of what I’m looking for as far as books.” He made a note to that effect on the submissions section of his website because, although zombie tales are great, that’s not the sort of work he’s looking to publish. Next up for Logosophia is a project by Henry Niese, an 89-year-old painter who hung out with Jackson Pollock. Niese has studied Native American Sun Dance ceremonies for decades, and the book will be about his experiences with them. “The role of the small press, right now, is to put out the books that are worthy and not sellable,” says Stephen. “Joyce couldn’t get his works published, and Melville couldn’t sell a book. All the things that are considered classic and great today had a hard time in their inception.”

Murray, of Ecco Qua, who will lead a writing workshop in Italy in October, says she feels “cautiously optimistic.” Although no one in the independent book business is getting rich, she says, they can stay afloat thanks to a devoted readership. “It’s so fundamental to who we are,” says Murray. “The human impulse is to communicate, and that is not going to go away.”

She adds: “It’s a story that’s still unfolding. Small presses have stayed the course. If you pace yourself, you can keep moving forward.”

Those are words that new publishers such as Hankins can take to heart, though, as with his colleagues, practicality has little to do with his motivation. “One of the reasons I want to publish books, rather than a magazine, is that periodicals are transient,” he says. “Books at least have a chance of becoming classics. If I’m publishing writers whose work I really believe in, I can give them a chance at being read for generations.”

Lark Books closes shop

Longtime local publishing house Lark Books announced last week that it’s closing its Asheville offices. The craft imprint will move in with its New York-based parent company, Sterling Publishing, which means a loss of 15 local jobs.

Lark was founded by then-husband-and-wife team Rob Pulleyn and Kate Matthews, who moved to Asheville in 1979. Over the course of the past 35 years, Lark not only dominated the craft publishing industry, but employed and showcased a number of Asheville-based artists, writers, editors and designers. Its catalog includes numerous books by locals, including several jewelry-making guides from Joanna Gollberg, The Complete Book of Retro Crafts by Suzie Millions and Ashley English’s Homemade Living series.

In a way, the history of Lark Books is the history of the larger publishing industry. The independent imprint was purchased by Sterling in 1999. Sterling was, in turn, acquired by Barnes & Nobel in 2003. But through those mergers, Lark continued to produce engaging books on crafts, photography, food and design.

Last August, The Center for Craft, Creativity & Design purchased the Broadway Street building occupied by Lark for decades. The publisher moved its offices to the upper floors — and the shift continues. In January, The Wall Street Journal announced that Barnes & Noble put Sterling Publishing up for sale, though Publishers Weekly reported earlier this month that, due to low offers, the sale was off for the time being. Lark’s next incarnation hangs in the balance. Sadly, it won’t be in Asheville.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.