September 6, 1994: Pat Robertson. May October 21, 2011: Harold Camping. December 21, 2012: … The Mayans? Wikipedia’s “List of predicted dates of the end of the world or similar events” will probably never stop growing.

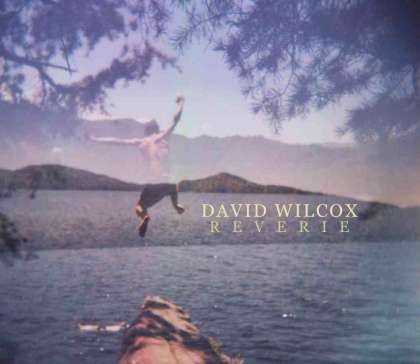

“Tell me ‘bout the calendar the Mayans figured out / Before they all disappeared in mystery / They didn’t have a future, but it seems we have no doubt / They knew the punch line of our history,” Asheville’s David Wilcox sings on the opening track of his latest album, Reverie. Most of the world has moved past the inane doomsday prophesying by now, but Wilcox makes it clear just how ridiculously presumptuous it is to believe an ancient lost civilization calculated the end of history. Apparently Camping and the likes aren’t just first-rate fodder for The Daily Show; they’re good material for sardonic modern folk songs, too.

Reverie is a live album without any applause. There’s no audible crowd noise or any sort of indication that Wilcox recorded these solo acoustic songs in front of his family and friends. The only real clue comes as the faint sound of a passing siren on “Dynamite in the Distance,” an eerie happenstance that ties the somber ballad’s many layers together.

The song is a good example of the multifaceted approach Wilcox takes in his songwriting. The story begins with a man planting explosives on the icy veneer of a river. “He’ll break the silence of the winter / for a price, for a price,” Wilcox sings. When a woman enters the scene, the iced-over river becomes a motif of fragile façades: “They were walking on the ice of all the things he’ll never say to her,” he sings. On the first level is a man haunted by what he’ll do for a price; on the second, a relationship, literally and figuratively on thin ice. And of course the only thing that stands to break the binate ice is money.

“When she hears the sound from far enough away / Even dynamite can purr,” Wilcox sings in the song’s final chorus as you literally hear the distant, soft and unobtrusive whine of an emergency vehicle siren, one that in direct proximity, is piercing and alarming. The proof to Wilcox’ claim somehow manifested itself within his song while he was recording it. Live. It’s unnerving, goosebump-inducing.

Past the troubles of a man, his money and a guarded relationship, Wilcox sings a caveat to human nature. A philosopher might call it moral distance: the fact that the farther removed we are from something, physically or temporally, the less we can sympathize. Dynamite is pretty easy to plant when you’re only going to hear it in the distance.

The politics are unavoidable on Reverie. Even though songs are tongue-in-cheek and meanings are concealed in Wilcox’ dry satire, tracks like “Little Fish” and “We Call It Freedom” are hardly subtle in their derision. Wilcox questions God, Jesus, the government, gives specific examples of history repeating itself and even makes a call to arms – Reverie is downright politicking. Only an activist like Wilcox could think articulating “Sultan Suleiman” and “Malik-al-Muattam” in a verse was a good idea. But Wilcox takes a mouthful and makes it work.

Wilcox defines himself with what he isn’t on Reverie. His constant use of tragic or Socratic irony combined with homonymic wordplay gives two sides, and often more, to each song. Wilcox is a strong guitar player, and honestly, the man could hold his own on an instrumental album, but the real profundity to Wilcox’ songs is in his lyrics.

He’s practically a homegrown Bruce Cockburn. If the Canadian folk singer had grown up in the States, I’d imagine he’d turn out exactly like Wilcox: more grounded in his storytelling and less forthright in his irony, where Cockburn’s lyrics are outspoken, Wilcox’ are illusory and subversive. If given the task of reimagining Cockburn’s “If I Had A Rocket Launcher,” Wilcox would probably rename it, “You And Your Rocket Launcher.”

Even the open, cathedral-ceiling studio Reverie was recorded in, Cincinnati’s The Monastery, presents itself with thin acrimony given Wilcox’ spelled-out distaste for organized religion.

Reverie is treat for longtime fans of Wilcox. The solo instrumentation and more flagrant politics combined with the intimate recording setting give the listener a chance to get to know what Wilcox really thinks, while still paying close attention to his dynamic fingerpicking. It might be preaching to the choir, but it’s a perfect fit for Asheville’s sound.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.