The title of Erica Abrams Locklear‘s new book — Appalachia on the Table: Representing Mountain Food & People — might suggest a cookbook chock-full of recipes for apple stack cake, ramps, liver mush and leather britches. But in fact, there are just two — one for blackberry pudding and the other for banana upside down cake.

Both are courtesy of the author’s late maternal grandmother, Bernice Ramsey Robinson. Images of her handwritten recipes appear in Appalachia on the Table and reveal the worn and fragile pages from the cookbook Robinson started in 1936 and continued to add to through 1952.

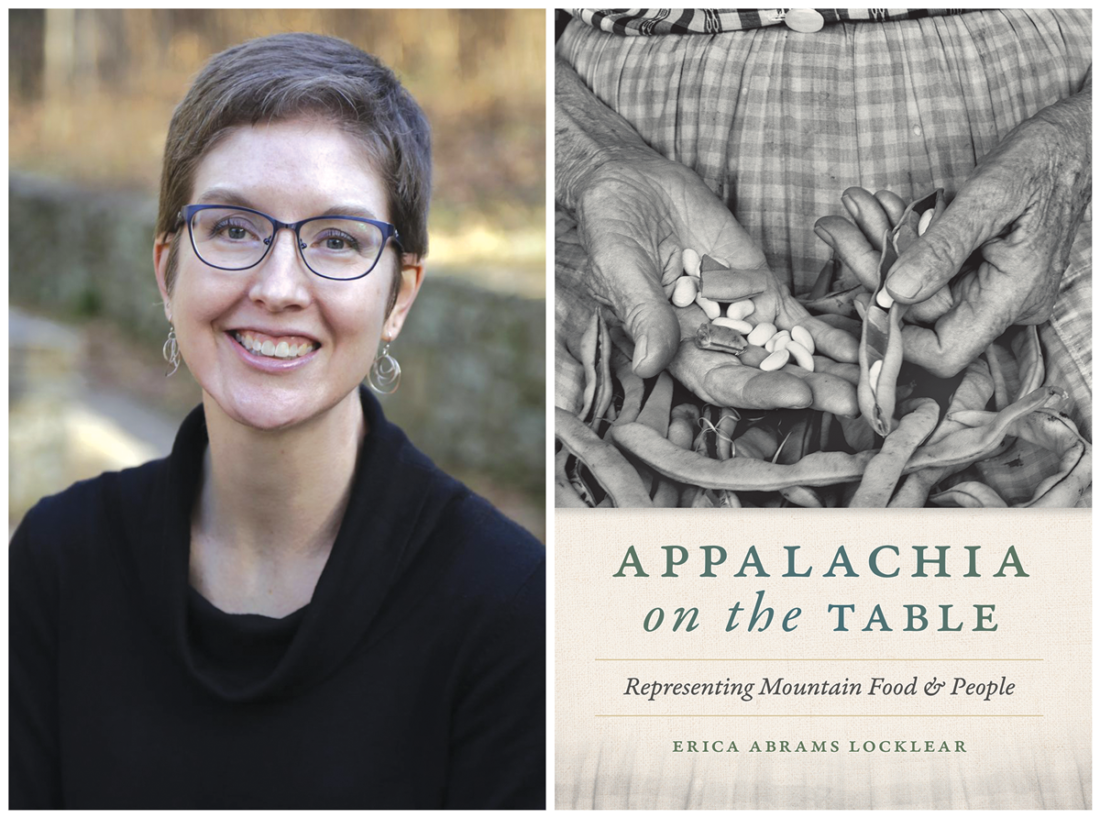

In Appalachia on the Table’s introduction, Locklear — a professor of English and the Thomas Howerton Distinguished Professor of Humanities at UNC Asheville — warns that readers seeking an authoritative list of “mountain” food will be disappointed.

Instead, Locklear, a seventh-generation Western North Carolinian, pursues a chronological path rife with literary references and rich in personal documentation that examines how mountain food went from what she describes as “the dominant narrative of culinary depravity” in the late 19th century to today’s cream of the crop.

On Tuesday, April 18, at 6 p.m., Malaprop’s Bookstore/Cafe will host Locklear’s launch party, where the author will be in conversation with John Fleer, chef and owner of Rhubarb.

Seeds of inspiration

“The evolution is kind of head spinning,” Locklear continues. “How foods associated with Appalachia and mountains — that were once considered coarse, unsavory, unsophisticated and unacceptable — are now trendy, foodie foods celebrated in restaurants and cookbooks.”

The book’s concept was inspired by a piece Locklear contributed to the 2014 collection, Writing in the Kitchen: Essays on Southern Literature and Foodways, edited by food scholars David Davis and Tara Powell. “I loved writing that essay and realized I had so much more to say and so many questions.”

Fate and timing fell in step in 2016, when Locklear’s grandmother’s cookbook was rediscovered by the author’s family. Robinson, Locklear notes, pasted her recipes onto black paper and filed them away in a leather photo album.

“It is a combination of handwritten recipes and others she tore out of newspapers and magazines and cut from product boxes,” the author says. “It was so well organized and blew my mind that despite working, raising three children and running a farm, she took the time to put this together.”

Before reviewing these recipes, Locklear admits, she had her own assumptions about the type of cooking her grandmother would have done — namely, apple dumplings, biscuits and chowchow. Instead, the author discovered a wide range of dishes, including royal fruit dressing, date nut fondant, streusel and fig pickles.

Locklear notes she was deeply touched by her grandmother’s instructions for blossom-time cake, which suggested bringing spring indoors by plucking blossoms from trees abloom in the orchard and dipping them in sugar to top the cake.

Tracing the trajectory

In 2017, Locklear took a professional development leave from UNCA and began figuring out chapter distinctions to move the project forward.

The opening chapter examines the origins of stereotypes associated with mountain food. “Local color” literature about Appalachia began appearing in the post-Civil War years and continued through to the early 1900s, writes Locklear. These publications, she continues, factored largely into the assumptions made about the region’s culinary practices and diet.

“Local color literature was almost always written by people not from the region they wrote about,” the author explains. “It was typically written in very heavy dialect, often juxtaposing beautiful landscapes with degenerate people. They were published in major, national outlets.”

In a later chapter, Locklear examines a statewide agricultural initiative called Live at Home, introduced by Gov. Oliver Max Gardner shortly after he took office in 1929. Conceived as programming to help sharecroppers and tenant farmers grow enough food to sustain themselves, the initiative assumed the obstacle for the farmers was a lack of knowledge rather than the true issue: lack of capital.

In this chapter, Locklear references writers Grace Lumpkin and Olive Tilford Dargan (pen name Fielding Burke) whose 1932 novels To Make My Bread and Call Home the Heart, respectively, depict the Live at Home concepts and their characters’ strong and affronted reactions to them. “Clearly [these characters are] thinking, ‘I can’t believe this man shows up in a fancy car, drives into my field and has the gall to talk to me like I don’t know how to grow squash,’” says Locklear.

In the Cooperative Extension archives at N.C. State University, Locklear learned that Live at Home dinners were held at the governor’s mansion, with state leaders and dignitaries seated at the table. Course by course and dish by dish, growers’ and makers’ names and locations were cited, including the milk, butter and scuppernongs for cold-pressed juice.

“The menu was essentially a 1930s version of farm-to-table, which is just fascinating,” Locklear notes.

Stigma to status

A thread Locklear says kept coming out through all her research was the idea of food shaming and social stigmas attached to certain foods. “I knew about cultural capital but didn’t really know about culinary capital, and the idea that what you eat can elevate or decrease your social standing. But that changes depending on time, place and context,” she explains. “That is the story of Appalachian food I’m writing, how food that was seen as a marker of low social class is now one of cultural cache.”

She points to sorghum as a prime example. “In the early 20th century, sorghum was a sweetener for poor people, and now it’s on the menus of high-profile restaurants by high-profile chefs like Travis Milton and Sean Brock.”

In the final chapter of the book, she discusses the current celebration of Appalachian food, reminding readers that Appalachian writers have been enjoying these meals long before they became trendy. She cites author and Tennessee native Robert Gipe and his graphic novel Pop.

“The protagonist Nicolette is from a deeply rooted mountain family devastated by mountaintop removal and drug addiction,” Locklear says. “She is taking cooking classes and experimenting with fancy dishes, making her family try them. They’re not well-received, particularly by her mother, Dawn, who refers to her as a ‘hillbilly Julia Child.’”

In Pop, the circle comes back around to apple stack cake; it is Gipe, Locklear says, who goes to great lengths to have his characters describe the intense and laborious process of making the dessert that some may consider a simple and basic dish.

Ultimately, Locklear notes that the recognition of and respect for Appalachian food is long overdue. But she urges proceeding with caution, echoing scholar Elizabeth Engelhardt’s advice in the essay “Appalachian Chicken and Waffles: Countering Southern Food Fetishism.”

“Building on her ideas, I think we need to be careful that we don’t become exclusionary,” says Locklear. “I think there’s a danger to even inadvertently perpetuating the stereotype of Scottish-Irish mountaineers and their foodways and ignoring indigenous people … [and] the contributions from African American and immigrant populations. Just because the food that was once considered coarse is now trendy, that doesn’t mean the problem is solved. National perceptions of mountain people are as problematic now as they have ever been, even as the food is venerated.”

Malaprop’s Bookstore/Cafe is at 55 Haywood St. To learn more about the upcoming event, visit avl.mx/prx7 All in-person attendees are required to wear masks.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.