The ringing sound of hammers on steel echoed through the valley at the Smith Mill Works, a small business community in West Asheville. The source of the clatter was the inaugural gathering of the United League of Armorers, held Nov. 4-6 at the Surly Anvil, a local armorer’s shop operated by John Gruber.

The event was an opportunity for aspiring and master armorers alike to network and share techniques. “We’re trying to rekindle the fire of armoring. Nobody is holding back any trade secrets here,” said David Halliburton of Fieldstone Metal Craft, based out of Northwest Arkansas. “Everyone is giving everything they know so the next guy doesn’t have to reinvent it, and we don’t lose another 50 or 100 years in this beautiful craft.”

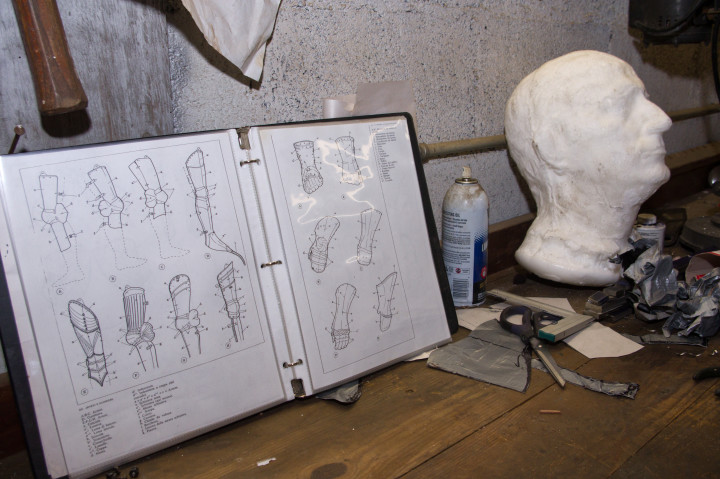

Halliburton, one of ULA’s organizers as well as an instructor, offered six hourlong hands-on classes in body casting, metal finishing and polishing. He described it as a “360 learning experience. You can watch a video or read a book but that’s still just two dimensional and armoring is a three dimensional art form.”

Many of the instructors and attendees have shared e-mails, photos and advice online, some for several years. But this conference was their first opportunity to meet in person. Mark Jameson traveled from Australia to attend, and he plans to stay on for another three months, learning at Gruber’s shop as a holiday. “Everyone is really supportive, sharing new ideas,” he said.

Jameson added that even little details instructors use while demonstrating techniques can answer questions about how to work smarter, not harder. “Someone will explain why they use a different technique or tool and suddenly it seems so obvious, like, ‘Why didn’t I think of that?’” he said.

Wade Allen, the owner of Allen Antiques just outside of Raleigh-Durham, brought his personal collection of antique armor pieces as a reference for authentic design study. Among his collection were examples of 15th century, delicately articulated gauntlets from Germany; 16th century Spanish breastplates; and a 17th century helmet called a burgonet.

The chance to examine these pieces, in person, offered a unique opportunity to “handle history” as Allen said. It was an opportunity to see, up close ,what tricks of the trade and solutions were devised by the armory guilds of their eras. “Armor in the Middle Ages and Renaissance was made for protection but also as a fashion statement, a status symbol. It’s really jewelry that you’re dressing up in,” said Allen, “so everyone knows how important you are on the battlefield.”

This is some cool stuff.