On Dec. 2, 1963 — 10 days after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated — Grant Stockdale, the deceased president’s former ambassador to Ireland, committed suicide in Miami. His son, Lee Stockdale, was 12 years old at the time.

Nearly 60 years later, Lee recently published his debut collection of poetry, Gorilla. While several of the poems grapple with his father’s death, the Fairview resident also explores other elements inspired by the many lives he’s lived as a New York City cabdriver, U.S. Army military police officer, Judge Advocate General officer and public defender in North Carolina.

“I don’t want Gorilla to be seen as a suicide book but as a journey of joy and healing, because that’s where it ends up,” Stockdale says. “I’m hopeful that readers are able to substitute my difficult event with any difficult event in their own lives and come away with their own feelings of joy and healing. I’m hopeful it’s a book readers may want to pass on to someone they think might benefit from it.”

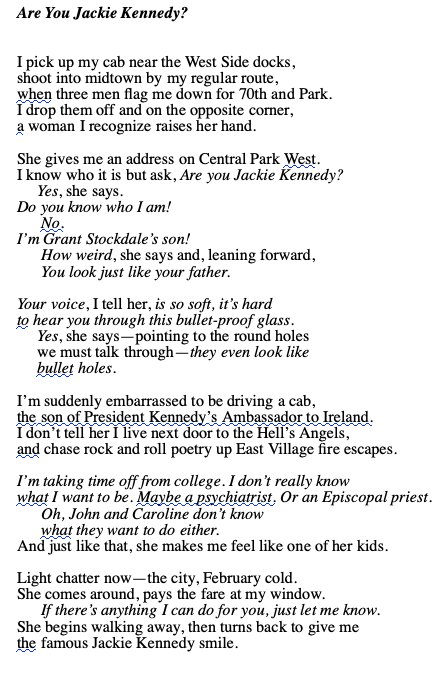

Xpress recently spoke with Stockdale about his past trauma, his early exposure to poetry and his passion for introducing others to the form. Along with the conversation is his poem “Are You Jackie Kennedy?”

Xpress: Take readers through the process of selecting this moment in your life to memorialize through poetry. How did you go about reentering the experience that resulted in “Are You Jackie Kennedy?”

Lee Stockdale: I was 12 when, 10 days after the assassination [of President John F. Kennedy], my father committed suicide. I was traumatized. And everywhere in America would spring new triggers for that trauma: Kennedy Airport, Cape Kennedy, Kennedy avenues. Meeting Jackie — and having her recognize me as looking “just like your father” — was truly healing. Her dear attitude made me feel like I should not be ashamed of my father but embrace him, be proud of him, find out who he was.

I would find out by doing things he had done: going back to college, enlisting in the military, going to officer candidate school, ultimately falling in love, getting married and having a family, as he had. Entering that cab, again, with Jackie, through that poem, was an easy and pleasant joy. I’m grateful she needed a cab that day.

When and how did poetry come into your life?

My mother was winning university poetry prizes before I was born, so poetry was always part of the family. I can still hear the nighttime staccato of her typewriter keys that put me to sleep. When she sold her first poem — to The Saturday Evening Post or Ladies’ Home Journal — the whole family celebrated.

In ninth grade, for Christmas, I got a used, standard-sized Royal typewriter, which did not excite me until I realized how physical writing could be. I used it more like a percussion instrument to pound out short stories, articles, poems, lyrics. Patti Smith was the first poet to induce me to change my life course. Immediately after hearing her read in New York, I moved into the Lower East Side. I was 22.

There is that moment in the poem when you become hyperaware of the situation that you’re in and embarrassed by it. There’s so much vulnerability in that stanza, which for me, is one of the joys of poetry. Can you speak to that aspect of the form and how, as a poet, you go about hitting such notes?

I try to express difficult thoughts in such a way that the reader sees, or intuits, the poem’s escape hatch. The very act of submitting an idea to poetry enters it into a kind of safe zone. I’m fortunate to have experienced trauma at such a young age. It gave me time to heal, to experience life, to be able to voice through poetry, “Yes, pain happens, but I made it through. You will, too.”

I’m a recruiter. Anyone can write poetry and be amazed at what comes out. It’s as if the poetry art form is an actual place of imagination anyone can walk into, like one walks into a house, a garden, a labyrinth. Poetry provides endless mystery to express joy, wonder, grief, the mundane, the incomprehensible sacred. I feel free and protected by this art form, allowed to be vulnerable, authentic, true to myself and my visions.

I love this idea of poet as recruiter. I don’t think it’s a stretch to also say that this particular collection is a plea of sorts to readers to discuss difficult topics, in particular, suicide. Can you speak to that aspect of Gorilla?

Shame, guilt, confusion, blame, suppressed anger, loss of a moral compass — this is where I spent 10 years after my father’s suicide, because suicide was too shameful to talk about. There was no vocabulary to discuss it.

I was blessed with a compassionate older sister and her wonderful husband, who took me under their wings, let me live with them for a time and introduced me to their friends, church community and a therapist. That therapy, in my early 20s, opened me up to what was churning inside, gave me light, began a healing. Before therapy, I thought I’d have to kill myself because my father had, and people said I was just like him.

I’m confident that family, spiritual and mental health resources are out there for anyone who desires to become more spiritually whole and mentally healthy. The courage to take that first step will absolutely be rewarded.

Is there a new collection of poetry by a local poet that you’re particularly fond of or excited to read?

I opened Keith Flynn’s The Skin of Meaning at random and read “The Justice System,” a surrealist poem that spun my head around so much, I immediately put the book down until I could carve out enough time to give the entire collection the focus it deserves. Keith is a master craftsman. The Skin of Meaning is a master work.

Who are the four poets on your personal Mount Rushmore?

Patti Smith, T.S. Eliot, Mary Ruefle, Louis Glück, W.S. Merwin, Alice Notley, Jillian Weise, Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Frost. I guess that’s more than four.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.