by Alex McWalters

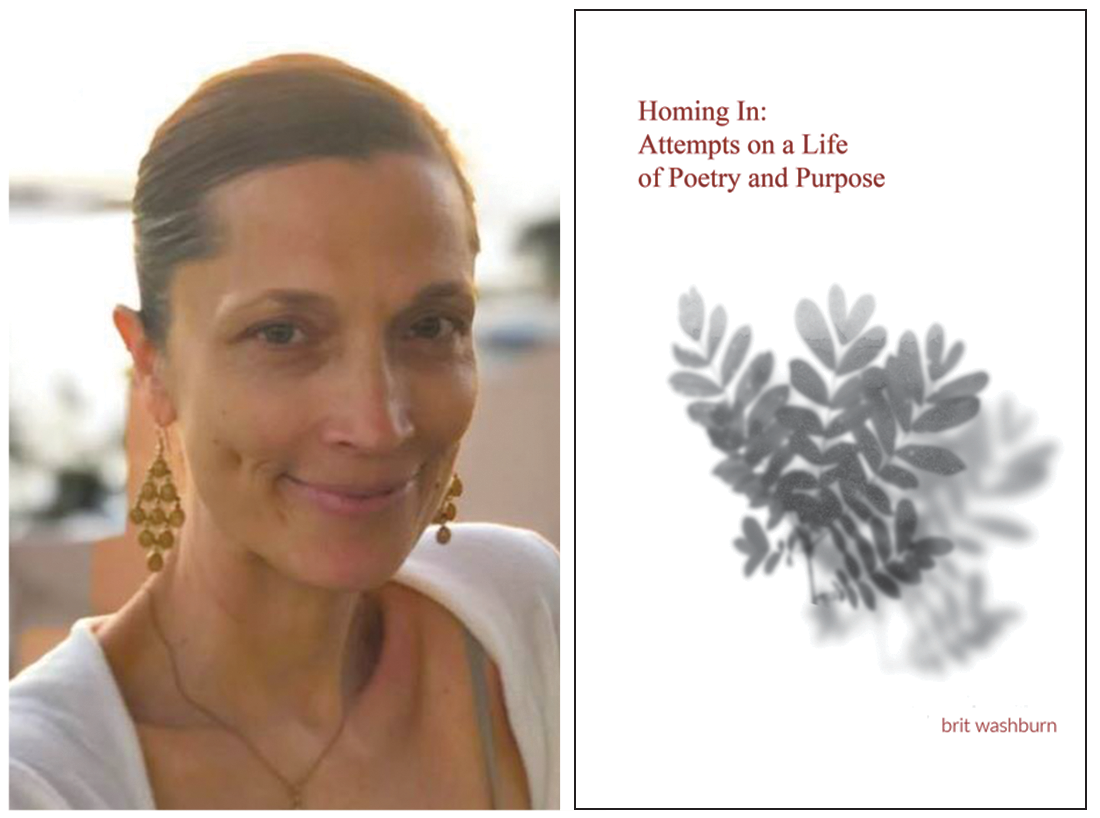

Pleasure, guilt, goodness, regret, confusion, self-respect and motherhood are among the many topics local poet and essayist Brit Washburn explores in her recently published collection of essays, Homing In: Attempts on a Life of Poetry and Purpose. And the author does so in often stunning precision and candor.

Whereas Washburn’s poetry, motivated by language and image, stands as a kind of prayer to the enduring perplexities of God and to the indefatigable passing of time, her essays are a glimpse into the complicated, hard-won convictions, practices and irreconcilable contradictions that underwrite the poignancy of her poetics.

“On the whole,” Washburn writes in Homing In’s preface, “these essays weave back and forth through time and subject matter, overlapping in places and leaping in others, but all have to do with the sometimes incommensurate selves we struggle to reconcile and contain.”

Quoting fellow poet Louis Glück in her author’s note, Washburn offers: “‘I wrote these essays as I would poems; I wrote them from what I know, trying to undermine the known with intelligent questions. Like poems, they have been my education’ — an education,” Washburn adds, “built upon reading, and trial and failure.”

Companion pieces

Like her 2019 poem collection, Notwithstanding, Washburn’s latest book took more than a decade to produce. But the relatively quick succession of the two works’ publications was, as Washburn put it, just a fluke. “In both cases, I was approached by the publishers, thank God, or all of this work would probably still be gathering dust,” she says.

“I never really had any lofty expectations or ambitions and just wanted to make my little offering on the altar of human feeling and thought. Then back to the salt mines,” she continues.

Fluke or not, the two books could be read as companion pieces, each a distinct but often complementary expression of, or inquiry into, Washburn’s own existential destiny.

Notwithstanding, a slim, elegant book, draws the reader’s attention to the pear on the table, the child’s tiny curled hand, a lover whom we long for despite our leaving, the golden child we knew inside the troubled young man, the lives we build that fail to nurture us. In the end, it is perhaps the value of attention itself, rendered with clarity and finely wrought detail, that Washburn’s verse asserts. “What is the pleasure of now?” her poems ask. “And what if now is all we have?”

Similar inquiries are investigated in Homing In. The collection opens with “The Edge: Of Motherhood and Poetics.” The essay was drafted in the spring of 2010, when Washburn was 35 and about to leave her husband of 15 years. The writings then progress, by and large, in chronological order, tracking with meticulous curiosity, scholarship and self-interrogation a poet’s complex wrangling with love, motherhood, art, spirituality, authenticity and solitude.

In “Living Yoga,” the collection’s second essay, Washburn writes: “My husband and I met when I was a 14-year-old student of creative writing at a boarding school where he, then forty, was teaching while married to his third wife. Five years later, he was divorced. I was dividing my time between New York and Paris, and we began a correspondence. A year after that, we were married, and now, fourteen years on, I am 35, and he is 61, we have three sons, and are coming undone.”

It is this undoing, and its long aftermath, that serves as Homing In’s narrative center, the event around which all Washburn’s interrogations — consciously and not — orbit. “[F]or all its romance and religious fervor,” she continues, “which were very real, in both yogic and psychological terms, our marriage has been replete with pathos, particularly ego and attachment, to which yoga ascribes so much suffering.”

‘Questions to be lived’

But as Washburn keenly articulates, her suffering did not end with the marriage — far from it. With the aid of the many poets, writers, musicians and spiritual texts that populate the pages of Homing In, Washburn wrestles with regret over having left the life and family to which she’d once been so wholly devoted; guilt, too, for the consequences her decision wrought upon her children.

And yet, as Washburn acknowledges in an email exchange with Xpress, “I can’t for the life of me imagine having survived and thrived had I stayed. I often wish I’d had a different destiny, one that involved prolonged domestic bliss, but I simply didn’t.”

Washburn’s meditations on love and motherhood are unflinching; her engagement with the incommensurate selves contained within her is candid. Like many artist types, Washburn grapples with her desire for solitude and freedom — to read and write, to engage with life’s big questions. Yet at the same time, she recognizes her competing need for connection and intimacy, for the pleasures of parenthood, even as she touts the value of commitment, devotion and altruism. How does one reconcile the seeker’s want for independence, adventure and knowledge with the Buddhist’s belief that seeking, in fact all desire, is suffering?

In “Authenticity vs. Faith, and the Fact of Fatigue” Washburn writes, “I believe that God will provide, that all suffering arises from departing from the present moment, from looking forward with anxiety or back with regret, wanting things to be other than they are. But depart I do, look back and forth I do, worry and pine for safety and security I do, and by suppressing or denying these impulses, this longing, I feel as though I am suppressing and denying something human and real.”

As this and other passages imply, Washburn’s Homing In offers no definitive verdict — not on God, the meaning of life, relationships or vocation. Such things are, she says, “not codes to be broken, but as Rilke had it, questions to be lived.”

In these pages, one encounters a woman living fully, tragically, joyously.

it sounds painfully delicious … and more than vaguely familiar. sigh. best of luck with all of it!