In 1927, more than 2,000 people combed the mountains of Western North Carolina in search of Broadus Miller, a Black laborer accused of murdering Gladys Kincaid, a 15-year-old white girl, in Morganton. Miller was found near Linville Falls. Commodore Burleson, a member of the posse, shot and killed him. Miller’s body was later displayed on Morganton’s courthouse lawn.

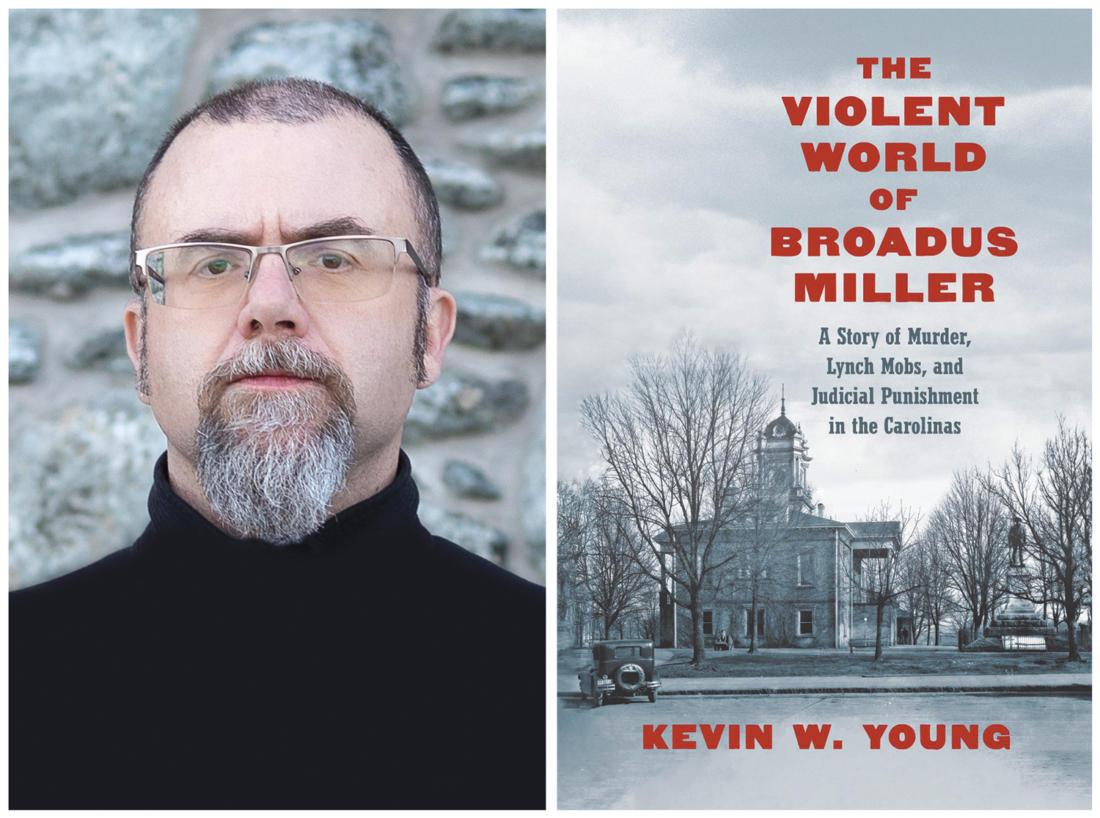

Kevin W. Young, a lecturer at Appalachian State University, has spent nearly two decades researching the topic for his newly released book, The Violent World of Broadus Miller: A Story of Murder, Lynch Mobs, and Judicial Punishment in the Carolinas. Young will give a talk on the topic, Tuesday, May 7, 6:30 p.m., at the Center for Pioneer Life, 134 Joe Young Road in Burnsville.

Xpress: What role does the city of Asheville play in your book?

In the early 1920s, the boll weevil laid waste to the cotton fields of South Carolina, causing many African Americans from upstate South Carolina — including Broadus Miller and his relatives — to move to Asheville, which was experiencing an economic boom and offered numerous job opportunities for manual laborers. This influx of Black South Carolinians caused a reactionary backlash from white residents, leading to great tension in race relations.

As I describe in the book, a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan was very active in the city; the Klan had the support of some of Asheville’s most prominent residents and maintained close ties with local law enforcement. In 1925, the backlash against Black immigrants from South Carolina culminated in a series of false accusations of rape that brought racial tensions in the city to a fever pitch. One of the falsely accused men would be convicted and spent five years on North Carolina’s death row before finally being pardoned.

What inspired you to spend 17 years researching this subject?

Back in 2006, I came across a brief mention of the Miller case in an article by historian Bruce Baker. I began going through microfilmed newspapers and learned that, for two weeks in the summer of 1927, the case had been headline news in newspapers throughout the United States. I started digging into census and courthouse records and discovered that Miller, a native of upstate South Carolina, was an orphan who had been adopted by his uncle and aunt — tenant farmers. In 1921, Miller had pled guilty to killing a Black woman in Anderson, S.C. A court-appointed psychiatrist examined him and concluded he was severely mentally ill. He was incarcerated for three years in the South Carolina State Penitentiary. Everything I learned about the case further fueled my curiosity. In many ways, this individual story seemed to exemplify much larger historical patterns of race relations in the early 20th-century South. This story deserved to be told, and I wanted to do it full justice.

How did your interviews with Gladys Kincaid’s siblings inform your work?

When you’re writing or reading about “true crime,” it can be easy to become so fascinated by the details of a case that you lose sight of the immense human suffering within every such story. Gladys Kincaid was a teenage girl whose father had died. She had to quit school and work in a hosiery mill to help support her widowed mother and younger siblings. When I began researching this case, I had the opportunity to speak with Kincaid’s brother Cecil and sister Elizabeth.

Talking with them made me keenly aware that her violent death had caused unimaginable grief for her family. Judging from the available evidence, it seems Broadus Miller did indeed kill Kincaid, and it would be wrong to minimize or ignore the pain his actions caused.

However, the events of 1927 caused many people to suffer. Around the same time that I spoke with Kincaid’s siblings, I interviewed a 90-year-old Black woman in Morganton; she still vividly remembered the terror she and her family had felt in the days following Kincaid’s murder, when all African Africans in the town had been threatened by angry mobs.

A few years later, I visited the rural church cemetery in South Carolina where Broadus Miller’s relatives are buried, and as I stood next to the grave of his aunt, I thought about how this woman also must have felt incredible heartache and pain. She had taken an orphaned and mentally impaired child into her home and had raised him as her own. And she had lived to witness that child grow up to be an adult who was hunted down and killed, with his body subsequently put on public display and then disposed of in an unmarked grave.

What have you learned about prison conditions in the Carolinas?

In the early 20th century, several commentators warned of the dire consequences of having a penal system that focused on making money through convict labor, not on reforming or rehabilitating prisoners. This emphasis on financial profit extended to every branch of the penal system, from operating sweatshops within penitentiaries to using chain gangs for road construction and maintenance, to running prison work farms that resembled antebellum slave plantations.

Conditions for mentally ill inmates were especially horrific. During the same time that I was researching conditions in the South Carolina State Penitentiary in the 1920s, The Atlantic ran a couple of articles about the present-day treatment of mentally ill prisoners in South Carolina. Reading these articles was sickening, for they described a prison system that was fundamentally the same as a century before, with mentally ill persons subjected to a disproportionate use of force and caged in small cells that were smeared with the blood and feces of previous occupants.

Incarcerating mentally ill people in hellish and brutalizing conditions, then releasing them — untreated, unrehabilitated and unsupervised — back into the world at large … well, that’s an appallingly obvious recipe for disaster. If the South Carolina State Penitentiary had truly been a correctional institution, instead of merely a punitive institution, then perhaps Gladys Kincaid’s death could have been prevented.

Would you characterize Broadus Miller’s death as a lynching?

The public exhibition of Miller’s dead body certainly resembled a lynching, but whether you characterize it as such depends on your definition of that term. In the early 20th century, anti-lynching activists generally defined lynching as a killing committed by a group of people “without authority of law.” Miller was killed by a single individual, and his death was legally authorized, for Burke County officials had utilized a provision of state law to designate him an outlaw, meaning any North Carolina citizen had a legal right to kill him if he tried to flee or resisted arrest.

Miller had grown up in a region where there were numerous lynchings — that is, illegal killings of African Americans by mobs of whites — and growing up in such a pervasively violent region undoubtedly played a role in shaping his own behavior. Both the violence committed by Miller and the violence committed against him are essential parts of this story, and it would be a profound mistake to focus entirely on one and ignore the other.

Neither of these two things excuses the other, and condemning one should never imply condoning the other. Violence spins in vicious cycles, and if you want to fully understand why these events in Morganton occurred, then you have to examine root causes that predate 1927. And if you want to come to a full reconciliation today for events that happened in the past, then you have to acknowledge the pain and suffering of everyone who was personally affected.

In Buncombe County, the Reparations Commission has been formed to make recommendations toward repairing damage caused by public and private systemic racism. What are your thoughts on reparations?

Anyone who researches the past immediately confronts the ugly truth of how extensive racism has been. In 1898, African Americans were essentially disfranchised at gunpoint in both North and South Carolina, with massacres occurring in Wilmington and other places, including Broadus Miller’s native Greenwood County. Throughout the early 20th century, political leaders in the Carolinas openly proclaimed white supremacy as a fundamental principle of state government. Racism was engrained within all aspects of the judicial and legal systems, from anti-miscegenation statutes to segregation ordinances. I believe that, in general, a necessary first step in repairing the damage is openly confronting the past and fully examining events such as what happened in Asheville in 1925 and in Morganton in 1927.

“Violence spins in vicious cycles”: that dark truth comes through in Young’s answers here. Thanks for his extensive work that went into this book and to Kiesa Kay for asking the right questions. Sad to say that too much of the brutality revealed here is still with us.