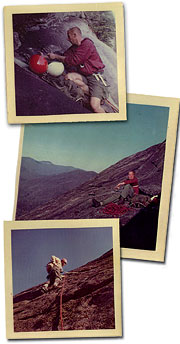

Rock of ages: In the top photo, Steve Longenecker puts the first bolt ever into Looking Glass Rock in 1965. Center: Longenecker has a contemplative moment at The Parking Lot tin 1966. Bottom: Robert John (“Bob”) Gillespie leads the second ascent of The Nose the same yearr. Photos courtesy Steve Longenecker.

|

On a chilly December day 40 years ago, Steve Longenecker, Bob Watts and Bob Gillespie became the first rock climbers to reach the top of Looking Glass Rock in the Pisgah National Forest.

Initially, the three aimed to complete a route known as “The Womb” on the dome’s north side. But after flailing there awhile, they pointed their pitons at a considerable span of exposed granite facing northeast, in the direction of the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Before they took that stab at history, though, they studied the route with all the focus of a team of G-men. Besides buzzing frighteningly close to the cliff in a Cessna (piloted by whitewater-paddling pioneer Frank Bell), the climbers kept vigil on the Parkway during a rainstorm to gauge the steepness of the face and determine whether any overhangs lurked above. After succeeding on a short portion at the base of the route on numerous occasions, the trio determined to finish the 450-foot vertical climb, which they did on Dec. 17, 1966.

“The day was pretty grey with some globs of snow on the face,” recalls Longenecker. “Why we chose that Sunday I’m not sure.”

Four decades later, the men’s route — now known as “The Nose” — has arguably been covered by more climbers than any other in North Carolina. At the time they pioneered it, though, they weren’t aware of the significance of their accomplishment.

“We never thought it would be important,” says Longenecker. “It was to us, of course, but we had no idea it would become so popular.”

Their achievement is indisputable, but on the 40th anniversary of one of the state’s most notable climbs, not everyone is celebrating.

Age-related illness

From select overlooks along the Parkway, The Nose — an aged glob of hardened lava — looks like an enormous forehead bulging from the forest, its timbered hairline receding slightly. On a clear day, it’s possible to visually follow a faded line up the face — the very route the three men pioneered in the ’60s. So many have climbed it since that a path has been etched into the rock. Most climbers seem to accept this undeniable impact, but what many others, including Longenecker, find hard to swallow are the conditions now found at the base of The Nose.

“It’s disgusting,” says climber Harrison Shull, the South Mountain Regional Representative for the Carolina Climbers Coalition. “The Nose area is a poster child for what we don’t want a climbing site to look like.”

In 1966, only a jeep track came near the rock’s base, and a thick canopy of woods pressed up against the beginning of the route. Since then, the gently graded Sun Wall Trail has channeled a steady tide of recreational climbers, school groups, wilderness programs and camps to The Nose and other popular climbs nearby. After so many years of foot traffic, the long, narrow section at the bottom is now devoid of growth, and layers of topsoil have been swept away, making the base the climbing equivalent of a superhighway.

“The climb is three or four feet longer than it once was,” says Longenecker, referring to the amount of trodden soil that has washed away from the base. He admits to feeling a measure of responsibility for the current conditions.

“Back then, we never thought hammering a piton in the rock was a big deal,” he says. “Other people made us aware that there’s a cleaner way to climb. On the same note, climbers and programs [now] are much more aware of how things are done at the bottom.”

Though the sport’s degree of stewardship has evolved since the 1960s, it may not have materialized in time for The Nose, where it will take decades for new growth to get established.

“If the impact were happening today, we would stop it. But I think it’s too late now,” Shull explains. “We need to be realistic. We should turn our attention to protecting areas that still have a chance.”

But getting that done may mean taking a more organized approach to monitoring climbing sites in the region. Limiting group size, providing “Leave No Trace” training, and delivering more restoration and site-management projects are a few starting points.

Brevard guide Adam Fox, who is president of the Pisgah Commercial Climbers Association (www.pisgahclimbers.org), has been a champion of the low-impact movement. “You can’t point your finger at any one person,” he says. “It’s going to take everyone with a stake in the area to figure out how to avoid the overuse.”

Still, the most persuasive enforcement may be the social sanctions imposed by fellow climbers. Longenecker recently approached a group at the base of The Nose and noticed several fresh branches of laurel and rhododendron lying in the sand. “I gave them their due,” he recalls.

Despite the woeful condition at the base, 40 years later Longenecker still has proud memories of that cold, late-autumn day. He still has the threesome’s original equipment (currently on display at Looking Glass Outfitters in Brevard), as well as news clippings about The Nose and Looking Glass Rock and snapshots of early climbs. Missing from his scrapbook, however, is an original photo of the base, unmarred by four decades of traffic. Hopefully, he’ll find it some day.

[Jack Igelman lives in West Asheville.]

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.