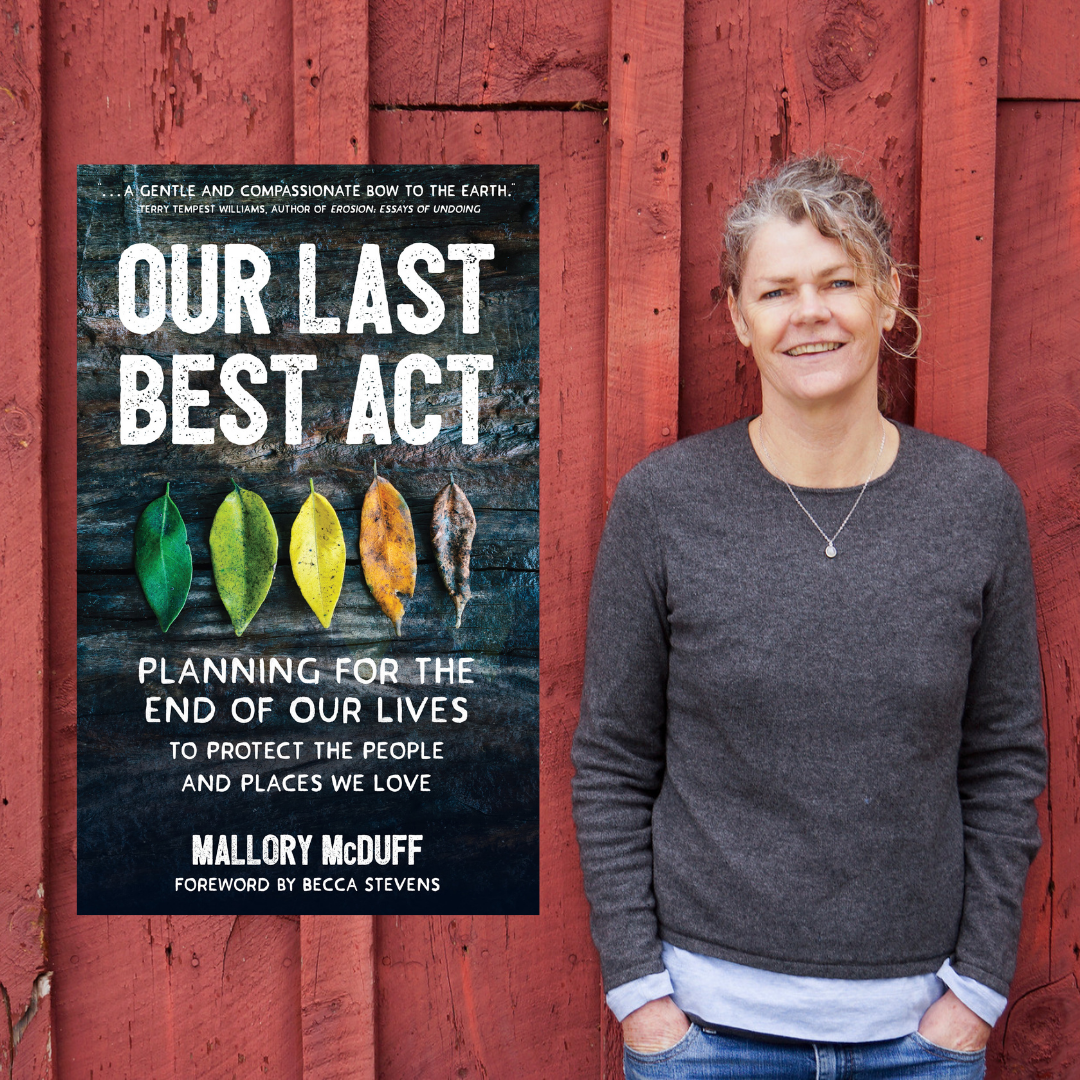

As a professor of environmental education at Warren Wilson College, Mallory McDuff is experienced in teaching the next generation about environmentalism. “Climate is front and center for them,” she says. With the Dec. 7 publication of her book Our Last Best Act: Planning for the End of Our Lives to Protect the People and Places We Love, she’s now educating anyone curious about a conservation-minded death.

The book begins with McDuff’s journey through her own parents’ deaths. Her father left directives for a conservation-minded burial, including no embalmment (due to the use of the toxin formaldehyde) and a handmade coffin. From there, she explores options like natural burial in conservation cemeteries, home funerals, flame cremation, mushroom-infused burial suits and other eco-conscious approaches.

Prior to researching the greener alternatives, McDuff’s own last wishes were to be cremated — that is, until she learned about the fossil fuels involved. The idea for the book formed during a presentation at All Souls Episcopal Church with Cassie Barrett from Carolina Memorial Sanctuary in Mills River that discussed the environmental impact of cremation. McDuff “realized that cremation is probably not the best option for me, given all the more sustainable choices that I have,” she explains.

McDuff continued to teach at Warren Wilson as she spent a year researching the book, examining each of the green funeral options available in Western North Carolina and revising her own plans. “I’d learned about more sustainable choices to leave the earth in the same way I’d tried, however imperfectly, to live on,” McDuff writes. “I saw the possibility of planning for death as my last best act for my children in a warming world threatened by more severe disasters, from blazing wildfires to destructive hurricanes.”

Going more gently

When planning their own deaths, many people consider a choice between two options: a casket burial, usually after embalmment, or a cremation. According to the National Funeral Directors Association, nearly 58% of Americans who died in 2021 chose to be cremated, with another nearly 37% choosing burial. However, according to the NFDA’s 2021 Consumer Awareness and Preferences Report, more than half of people report an interest in exploring “green” funeral options.

A conventional burial involves a number of items that don’t readily decompose. Caskets and vaults often contain parts of steel, copper, bronze and concrete. And embalming fluid, which slows the body’s decomposition process, contains formaldehyde — “a highly toxic systemic poison that is absorbed well by inhalation,” according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC notes that the toxin irritates the respiratory tract and skin and can cause dizziness and even suffocation.

A green burial, or natural burial, is done without embalmment of the body and without the use of a vault or metal casket. Neither a vault nor an outer container is required by North Carolina state law, but cemeteries have the right to require either, according to the N.C. Funeral Directors Association. State law also does not require that the deceased be embalmed.

Ten funeral providers in North Carolina were certified by the Green Burial Council as of October, according to New Hampshire Funeral Resources, Education and Advocacy, a website that collects nationwide information about green funerals. All Green Burial Council-certified final resting places — there are 340 providers nationwide — are not the same. Some are natural cemeteries, which are fully committed to sustainable practices, and others are hybrid cemeteries, where both green burials and conventional burials occur. The Green Burial Council certifies compliance with its standards for designation as a hybrid cemetery, natural cemetery or conservation burial ground.

Forest Lawn Memorial Park Garden in Candler and Green Hills Cemetery in Asheville are both hybrid cemeteries. Carolina Memorial Sanctuary is a conservation burial ground; the land is protected in perpetuity by a conservation easement.

Funeral homes can also be Green Burial Council certified, including eight in North Carolina. For example, Groce Funeral Home, which has offices in Asheville and Arden, offers green burial as a “specialized funeral option.” This option uses caskets from Aurora Casket Co. made out of pine and wooden dowels, nontoxic wood glue and straw bedding. Instead of embalming the body, Groce uses refrigeration units.

“One thing that I did learn during the research is that there are so many local funeral directors who are doing amazing work in collaboration with some of these green options,” McDuff says.”

Different decision-making has to come from all angles of the funeral process. “I’m trying to be clear in the book that one individual action — like one person getting buried at Carolina Memorial Sanctuary — that’s obviously not going to transform climate change,” she continues. “But I do think that those individual actions, and thinking about climate and community, we do have the capacity to shape how our culture deals with death and dying.”

Good grief

A green funeral can be an important grief ritual for loved ones, says Asheville-based licensed mental health counselor Katherine Hyde-Hensley. A grief ritual is meant to both comfort the bereaved and provide symbolism about the individual’s life. “Honoring a chosen ritual, such as green burial, to remember and celebrate a life is essential in a healthy grieving process,” she says.

Hyde-Hensley notes that prior to the mid-19th century, families prepared the deceased at home for burial and that immediacy may have led to an easier acceptance of death. In her experience, she continues, “the simplicity, gentleness, and honesty of green burial create a feeling of intimacy.”

Many loved ones don’t receive specific wishes about how the death of a relative should be handled. Throughout her research for Our Last Best Act, McDuff saw how making plans to be laid to rest in a conservation-minded way is an entry point for the living to engage with death.

“I found that once I started talking about this, people wanted to talk,” McDuff says. “I think it’s because we don’t often have those opportunities to talk about [death] that it became a topic of conversation.”

Everyone dies alone, McDuff notes, and she acknowledges that the topic can sometimes feel isolating. “But in the talking about it — I realized with my father’s death — planning can be a part of a community.”

She notes, for example, that she has now had conversations about green funerals with her neighbor, as well as her teenage daughter, whose reactions to her mom’s unusual research subject provide comic relief through the book.

The connection of a community to the Earth is what Ben Gordon, a former student of McDuff’s at Warren Wilson College who works as a land steward for Carolina Memorial Sanctuary, finds meaningful. “How a community relates with death is foundational to how a community relates to itself, other communities and the Earth,” he says.

Maintaining the land on which green burials take place is meaningful and important work, adds Gordon. “[The] way that a community handles death — with respect and reverence towards all kinds of other things that are also living and dying in a given area — is as good of a direction we might have in our current society in terms of how to relate with death as a community,” he says.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.