As a young woman, Winslow Umberger could easily sleep through the night. But when she got older, she started having to get up to use the bathroom. At first, it was one or two trips a night, and she had no trouble getting back to sleep. “I chalked it up to having had three babies,” she says, adding, “It’s just part of aging.”

Over time, though, those trips became more frequent, and while she could still get back to sleep, she didn’t feel rested in the morning. “When I got to seven times a night, I knew I had to do something,” she recalls.

A urologist suggested she try Kegel exercises, which contract and release the muscles of the pelvic floor, and also offered medication that would reduce the urge to go when the bladder isn’t full. But the exercises didn’t help much, and Umberger was reluctant to take medication or have surgery, so she began exploring other options.

The pelvic floor muscles keep the bladder, rectum, uterus and prostate in place, and when they’re not healthy, it can lead to a range of issues. Further complicating matters, embarrassment often deters people from talking about these problems, which are not exactly dinner table conversation. Instead, they may simply try to cope with the situation themselves rather than seeking treatment.

Umberger, however, says, “I’m a living organism and I know that, so I’m not ashamed to ask for help.”

Less is more

Being older and having had babies are common causes of pelvic floor dysfunction; other risk factors include injuries, certain surgeries and being overweight. The dysfunction can lead to problems with either constipation or incontinence, depending on whether the muscles of the pelvic floor are too weak or aren’t flexible enough. And though the condition is more common in women, it also occurs in men and can lead to pain, constipation, erectile dysfunction and urinary or fecal incontinence.

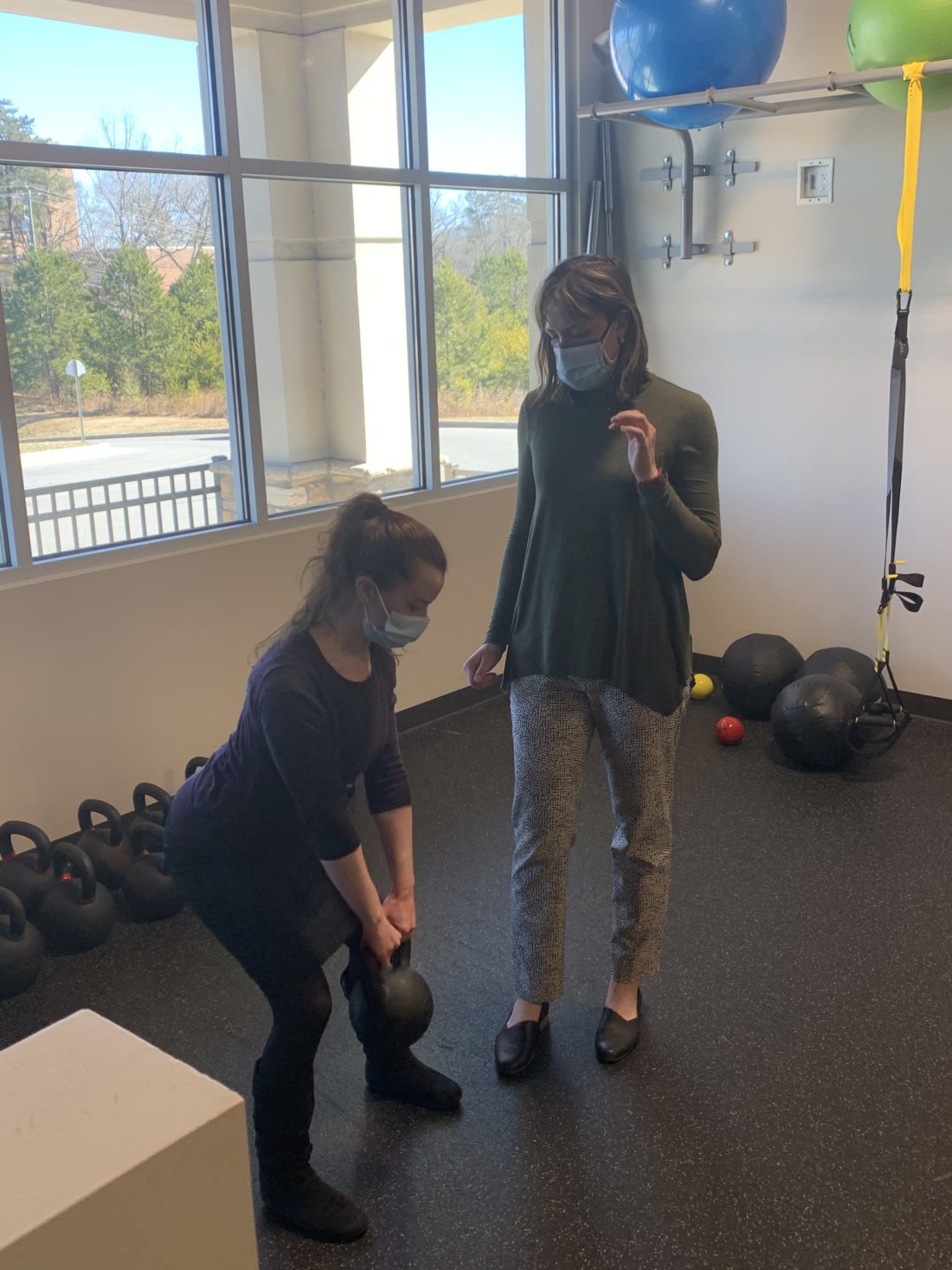

Drugs are usually tried before surgery, but while either may relieve symptoms, Umberger wanted the least invasive treatment she could get. Having read that physical therapy could help strengthen those muscles, she made an appointment with pelvic floor specialist Zoe Martin of Specialized Physical Therapy (which will change its name to Movement for Life effective March 1). “This therapy has only become common in the last five to 10 years, even though we know how helpful it can be,” says Martin. And because it’s noninvasive and doesn’t involve medications, she believes it needs to be the first line of treatment for pelvic floor dysfunction.

Training for the specialty can take four or five years, she explains: Getting certified as a pelvic floor rehab practitioner requires 2,000 licensed hours of direct patient care in the last eight years, 500 of them in the previous two years, and then passing an exam. Martin says she’s now most of the way through the process.

The fact that the dysfunction affects women more than men also helps explain why the problem was ignored for so long, says Martin. Historically, women’s health concerns have often been overlooked, resulting in poorer outcomes from such ailments as heart disease and some cancers, and increased suffering from issues related to pregnancy and childbirth, such as postpartum depression and sexual dysfunction. Against that backdrop, being able to help her patients get relief is part of what makes her specialty rewarding, notes Martin.

Amanda Hayes Fugate also offers pelvic floor therapy through her private practice, Pelvic Forward. Like Martin, she treats both women and men. “People are happy to learn they don’t have to take medicines or have surgery,” she says, adding that she’s seen a definite rise in demand for the therapy over the years. “I think people are more open about things today: Celebrities are very open about having babies and the problems they experience. That raises awareness.”

A personalized approach

Treatment begins with a thorough physical exam, which Umberger admits she didn’t look forward to. “But I was surprised,” she says. “It was thorough, and Zoe explained everything to me. It helped us figure out what I needed to do.”

The evaluation doesn’t focus solely on the pelvic floor: It also includes the lower back, hips, core and surrounding muscles, nerves and joints. Afterward, says Umberger, Martin prescribed a combination of therapy techniques and a tailored exercise program including both the Kegels and core muscle strengtheners.

And though the exercises did work, “Some of it seemed counterintuitive,” notes Umberger.

For example, Martin told her to drink at least six glasses of water a day. Part of her problem had been that she was dehydrating herself to try to reduce trips to the bathroom, and dehydration can irritate the bladder, making a person feel the urge to urinate even when it’s nearly empty.

“She told me not to do preemptive runs to the bathroom before going shopping or before bed,” Umberger recalls. Doing so doesn’t help and in fact can make the problem worse.

Umberger kept a log of her exercises and her progress, and after six weeks she noticed a marked difference. “I know I have to keep up the exercises, just like with any exercise,” she says. “And since I’m happy with the improvements, it has become a part of my day.”

Martin, meanwhile, says she’s not surprised that the therapy has helped. “I have patients who have been dealing with these problems for years and nobody has listened to them. They’re so relieved and so grateful when I’m able to help them.”

Wow. Thank you for this story and these awesomely candid resources! I came across this story because we are visiting the area, but I suffer from PVD. It’s life changing and hardly anyone knows. ✨ Thank you 🙏🏾