As it happens Halloween falls on a Monday this year and while that’s a pretty crummy day for Halloween to permit itself the luxury of occuring for most people, it actually works out rather nicely for me. You see, to the degree that I have a day off—and let’s face it, this is generally a seven-day-a-week gig—Monday is that day. At least, I’m not writing reviews and I don’t have to go anywhere, so I can spend this Halloween in the company of my favorite horror movies. Sometimes I’ve been known to take the coward’s way out and just turn on TCM on Halloween, but I’m not that keen on their line-up this year, so I’ve come up with with nine choices of my own (that seems the largest number I might realistically get watched). And being that horror is one of my favorite genres, all this meant was a trip over to the shelves.

Now, let’s face it, I’m something of a classicist where horror is concerned. And by that I do not mean subscribing to the idea that Friday the 13th (1980) comes under the heading of “classic,” though these days it’s frequently labelled as such—something that gives me as much or more pause than encountering a toy from my childhood in an antique shop. (Youngsters, it will happen to you.) No, I mean classics as in the “golden age” of horror—1931-1936—or the so-called “silver age” (more like tin, truly)—1939-1946. At least, that’s what I primarilly mean. There are exceptions. I don’t swear I’ll run these chronologically, but I’m going to present them that way. And bear in mind that since I’ve been involved in running one horror movie a week with the Thursday Horror Picture Show for about a year-and-a-half, I’ll likely be passing over films I would otherwise include, but have seen recently.

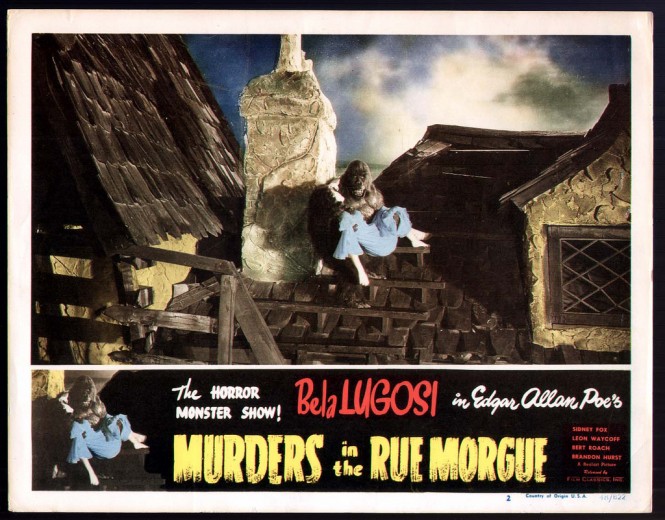

Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932). Probably the most disdained of all of the original Universal horrors from the 1931-36 period, Robert Florey’s Murders in the Rue Morgue is a film I’ve been defending for years. I even wrote a long article on it for the now defunct magazine Phantasma. (No, the article is not why the magazine is defunct.) And for all that, I realize that this is one very imperfect film—something that can be pretty much laid at the feet of Robert Florey, a man who rarely made a film lacking in interest and never made one that wasn’t deeply flawed. This one is no different—except that it’s probably his best.

The film was kind of a consolation prize for both the director and star Bela Lugosi. Florey had been the original director of Frankenstein back when it was slated to have Lugosi play the Monster. The stories of how that project became James Whale’s and how Boris Karloff wound up playing the Monster are so conflicting that it seems unlikely they’ll ever be straightened out at this late date. The major point is that after the success of Waterloo Bridge (1931) Universal wanted to keep James Whale happy, so when Whale decided he wanted to make Frankenstein, Florey—whose contract was for a film, not a specific one—found himself and his star making something this film instead. It was almost certainly a better use of everyone’s talent.

As is almost always the case with movies made from Edgar Allan Poe stories there’s not a lot of Poe involved, though Murders does retain some basics and—somewhat mystifyingly an insipid comedy bit where witnesses argue over what “foreign” language they think the ape noises they heard were. What Florey really made was a very peculiar reworking of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)—with elements of Poe and Charles Darwin, all wrapped up in one of Lugosi’s most compelling performances.

One of the most intriguing elements of the film is the exceedingly grim and twisted picture it presents of Paris—something completely out of keeping with the image of the city as put forth in most if not all Hollywood films. Once, the Berlin born Ernst Lubitsch—one of the main purveyors of a romanticized Paris—commented that he’d been to both Paris, France and to Paris, Paramount, and on the whole he preferred Paris, Paramount. Well, if the Paris-born Florey’s notion of Paris is any barometer—even in a period setting—it’s hardly a surprising choice. Florey’s is a decidedly sour vision. At one point, the hero, Pierre Dupin (Leon Waycoff), even—in a romantic moment, no less—goes on about how it’s better not to know what’s going on behind the windows of the houses of Paris, since they’re hiding “broken hopes and bodies and hearts, absinthe dreams, starvation and madness, crimes of the street and tragedies of the river—Paris, my city.”

Romantic it may not be, but it’s a perfect environment for Lugosi’s Dr. Mirakle, a scientist of Darwinian notions (sort of), who makes a living by running a sideshow where he displays his pet gorilla Erik (“the beast with a human brain”) and lectures on evolution to a pretty unsympathetic crowd. Indeed, it’s hard to understand how his pitch keeps going since he harangues his audience, calls them fools and insists, “I tell you I will prove your kinship with the ape!” The only exception to his outburst is Camille L’Espanaye (Sidney Fox) and her party—including medical student Pierre Dupin—mostly because Erik seems to like her.

The whole point, you see, is to mix gorilla blood and human blood. It’s never stated, but this doesn’t seem to be an end in itself. Rather the implication is to breed Erik with some hapless female. The problem is that all the women Mirakle has injected with gorilla blood have died on him. This is one of those things where a very unscientific bit of science gets dragged in—seems he needs to find a girl with “pure” blood, i.e., a virgin. This being the case, one wonders why he’s been experimenting on prostitutes. No matter, this loopy idea sets up one of the grimmest scenes in any classic horror film where Mirakle experiments on one hapless hooker (future What’s My Line? panelist Arlene Francis), berating her and her blood (“Your blood is rotten! Black as your sins!”) when it doesn’t mix with the ape blood. That he seems truly shocked and even distraught when she dies is almost more disturbing—as are the scene’s strange bits of religious symbolism.

Much of the film is given over to the concept of Dupin becoming so obsessed with Dr. Mirakle that he’d turning into him (Waycoff even starts to resemble the scientist), which is clearly from the idea of “becoming Caligari” that was expressed in that film. All of this—and much more—is absolutely fascinating, but there are a lot of problems. They start with Sidney Fox as Camille (one of “Uncle” Carl Laemmle’s attempts to create a star), continue with the ill-advised inserts of a real ape (definitely not a gorilla) rather than leave Erik as Charles Gemora in his ape suit, and wind up with an ending that feels rushed and perfunctory (even if it does logically free Pierre from his fixation). That said, this remains a personal favorite. (Don’t worry, I have no plans to be this loquacious on all the titles.)

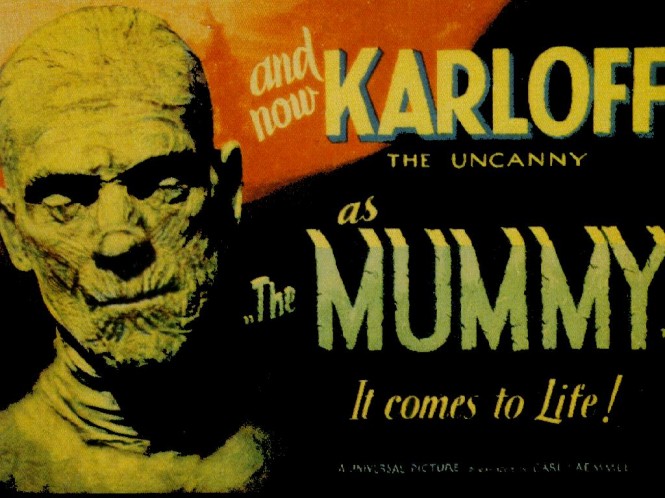

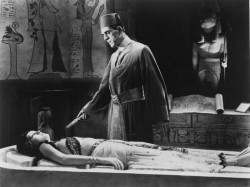

The Mummy (1932). Karl Freund’s The Mummy is one of the more traditional titles on my list. It’s the first movie attempt at turning a mummy into a movie monster and the first of Boris Karloff’s horror films in which he was given dialogue. What it is not is a mummy movie in the sense that most people think. Yes, Karloff’s Imhotep first appears in full mummy wrapping regalia, and it’s that image that was used even in 1932 to sell the movie. But if you’re expecting the shambling bandaged horror that Universal would popularize in the 1940s, you’ll be surprised to find that Karloff’s Mummy remains wrapped only in the film’s opening sequence. For most of the film, he simply appears as an impossibly wrinkled old geezer calling himself Ardath Bey.

The story is more a reincarntion yarn than a standard horror movie, and it owes more than a little (though it pays no credit to) the Arthur Conan Doyle short story “The Ring of Thoth.” Even the appearance of Ardath Bey has its origin in the story—” There was no suggestion of pores. One could not fancy a drop of moisture upon that arid surface. From brow to chin, however, it was cross- hatched by a million delicate wrinkles” and “‘Where have I seen such eyes?’ said Vansittart Smith to himself. ‘There is something saurian about them, something reptilian. There’s the membrana nictitans of the snakes,’ he mused, bethinking himself of his zoological studies. ‘It gives a shiny effect. But there was something more here. There was a sense of power, of wisdom—so I read them—and of weariness, utter weariness, and ineffable despair.’”

The film offers a Scroll of Thoth rather than Conan Doyle’s elixir vitae and the Ring of Thoth, and is fanciful in a different way. Where Doyle’s ancient Egyptian has been wandering the earth all this time, Ardath Bey has been doing the big sleep for 3700 years till a hapless Egyptologist reads the Scroll of Thoth (“which contains the spell with which Isis raised Osiris from the dead”) within earshot of the mummified version bringing the old boy back to life.

It’s the reanimated mummy in the person of Ardath Bey who tips off a later expedition where to find the tomb of his old flame. This is not Egyptological altruism, min you, but because he has it in mind to raise her from the dead once they dig her up and put her in the Cairo Museum. The problem with this scheme is that she’s been reincarnated as Helen Grosvenor (Zita Johnann). This leads to a new scheme that boils down to Dr. Muller’s (Edward Van Sloan) sudden realization that “he’s going to kill her and make her a living mummy like himself.” Well, of course. And if all this sounds mighty familiar, it ought to because it’s essentially Dracula (1931) all over again—complete with Edward Van Sloan as an ersatz Van Helsing. It’s also slicker and better—though no more hurriedly—paced. Considering the screenplay is by the co-author of the original 1927 stage play of Dracula, John L. Balderston, this is perhaps not that surprising.

Much like Dracula, too, The Mummy is a mood piece. That’s what makes it so effectively creepy. Part of that is the fluid direction of Karl Freund. Part of it is the effective score (the first Universal horror with background music) by James Dietrich. But a lot of it comes down to Karloff in one of his best performances. His deliberate line readings manage to convey both the power and the patient assurance one might expect from a 3700 year old man. What is most remarkable is that you never once question that his Ardath Bey actually is that old—and since you’re fully aware that it’s all the outrageous moonshine, that’s no small achievement.

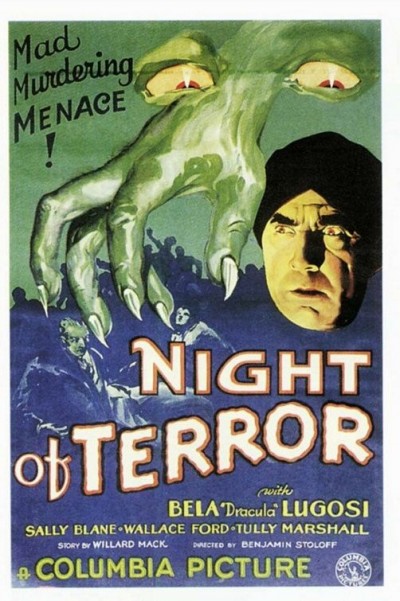

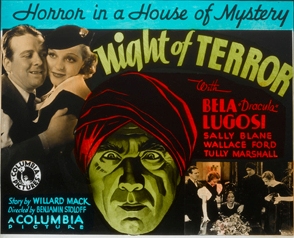

Night of Terror (1933). It’s hard to say whether or not Ben Stoloff’s Night of Terror is actually a B picture or a low-end A picture, since at the time it was made nearly all Columbia pictures showed a distinct paucity of budget. My guess is that it’s the latter—the studio’s first flat-out attempt to make a horror movie. It’s also the very first film that can truly be called a personality vehicle for Bela Lugosi. A lot of people have dismissed the movie over the years as “wasting” Lugosi in the role of a servant. That strikes me as completely wrong-headed. First of all, this isn’t one of those films where a studio cashed in on his presence by giving him a couple days work standing around doing nothing. His Degar is very integral to the proceedings and is hardly just standing around doing nothing. Yes, he’s a red herring, but so what? As a kid I actually thought it was very cool that not only was he not the bad guy, but was actually the guy who solved the murder.

The real point about Night of Terror is that it marks the first time where Lugosi is in a film that is so clearly designed as a Bela Lugosi vehicle. This is a film where nearly everything Lugosi does is tailored to the concept of the fact that he simply is Bela Lugosi. Some things he does purely because they’re the sort of thing he would do. Even his entrance—with the camera dollying in to a close-up a panel in a door when Tully Marshall opens it—serves no purpose but to announce “this is Bela Lugosi and he’s mysterious.” And if that doesn’t strike you as a good thing, then this movie isn’t for you. Maybe Lugosi isn’t for you altogether, come to that.

The film is essentially an old dark house affair of the Cat and the Canary school, though the lunatic-on-the-loose here—called The Maniac and played by Edwin Maxwell in the film’s coda, but otherwise by somebody else (some sources claim Pat Harmon)—is a very present and active fellow. When the film opens he offs a young couple (the male half of which is an unbilled Dave O’Brien) in lover’s lane—bringing his mortality total up to 12. The Maniac is pretty clearly the Jason Voorhees of his day and Night of Terror is the granddaddy of all made slasher movies. Granted, The Maniac has a little more style, since he always leaves a newspaper clipping about his last murder on the corpse. (One wonders what he did for the first one.) Before the movie’s over, the body count from him is up to 14.

As luck and skillful writing would have it, our serial killer has wandered into the area of the Rinehart (a nod to author Mary Roberts Rinehart?) Estate—and manages to hang around there an incredible length of time, since the police know he’s around, but you go with this sort of thing in this type of movie. The Rinehart Estate just happens to be where Arthur Hornsby (Bryant Washburn) is about to show off his new formula for suspended animation by having himself buried alive. And he almost misses the chance when The Maniac nearly gets him. Fortunately for the plot, Arthur is saved the arrival of his uncle Richard Rinehart (Tully Marshall). The Maniac goes out the window and settles for killing the gardener who’s digging Arthur’s grave.

The Rinehart household is a rather strange place at best. It not only contains Richard Rinehart and his nephew Arthur Hornsby, but also Rinehart’s ward Mary Rinehart (Loretta Young’s older sister), who, it appears, is engaged to stick-in-the-mud scientist Arthur. Despite that, when we first meet her Mary’s out with wisecracking reporter Tom Hartley (Wallace Ford in the first of his many wisecracking reporter roles). The household also includes Degar the butler, his alarmingly trance-prone wife Sika (Mary Frey in seemingly her only movie), and Martin (Oscar Smith), the inevitable scared black chauffeur. Most of them seem to skulk around a good bit, so it’s hardly a surprise when Richard Rinehart is murdered later that evening—supposedly by our pal The Maniac, though Tom Hatley claims the lack of a newspaper clipping proves it wasn’t him. This, of course, merely annoys cigar-chewing Detective Bailey (Matt McHugh, lesser-known big brother of Frank McHugh).

The film skips happily ahead to just after the reading of the will with Rinehart’s relatives now added to the mix. The will, of course, is one of those “invitation to murder” affairs where the shares increase with every death among the heirs. Naturally, that’s just what transpires—and it doesn’t help that The Maniac is still loitering in the area. Look, you’ve got murders, you’ve got mysterious vaguely Hindu servants, a wisecracking reporter, a pretty heroine, a blustering dumb cop, a scene where Lugosi drugs a cop with “an…Oriental cigarette,” a seance, and The Maniac getting up from the dead at the end to threaten you with what he’ll do to you if you reveal the ending. How can anyone not love this movie? (Side note: Sony Entertainment doesn’t seem to realize its merits, that’s for sure, since they seem disinclined to bring it out even as a DVD-R on demand. I don’t personally know a horror fan who wouldn’t but it at once.)

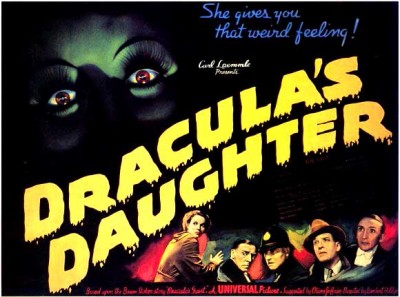

Dracula’s Daughter (1936). OK, so this ought to have been a super production—or a “Universal Jewel” as they were called in the silent era (then it meant some attempt had been made to make a good movie)—and it had once been slated to star Lugosi as Dracula (back from the dead) and to have been directed by James Whale. (Whale even incorporated an in-joke about it into his 1935 mystery-comedy Remember Last Night?.) So things changed. The production was scaled back. Whale was dropped. Lugosi was bought out of his contract to be in the film (supposedly for more money than he was paid to be in Dracula). Lambert Hillyer (mostly known for cowboy movies, but he’d done a credible job on The Invisible Ray the previous year) was brought in and a dummy that looked nothing like Lugosi was stuck in his coffin (and later burned). The only holdover from the original was Edward Van Sloan as Prof. Van Helsing—except he seems to have become German rather than Dutch in the intervening years and is now Von Helsing.

With all this working against it, Dracula’s Daughter should have been a lox, but, no, it’s actually a very good, very fast-paced, very well acted, atmospheric film. It also points an interesting direction that the horror film might have gone had this not been the final Universal horror picture for three years, and this may be the major holdover from when Whale was planning the project. The romantic leads—Otto Kruger and Marguerite Churchill—aren’t your usual insipid juveniles. (For that matter, Kruger was 51.) Instead, they’re an intelligent couple of the screwball comedy variety—and the material afforded them (often heightened by Heinz Roemheld’s score) is pretty funny, and made more so by their playing. We can actually like and care about these two.

The story picks up right where Dracula left off (though somehow at the bottom of the stairs to Frankenstein’s lab)—only the cops have arrived and promptly arrest Von Helsing for murdering Dracula. Now, just what happened to those folks whose hash he’d just saved is never addressed, but that paves the way for the Professor to need to call on psychiatrist Jeffrey Garth (Kruger) because “he alone will understand.” Well, he doesn’t understand, but the case against Von Helsing becomes a little sketchy because a mysterious woman—Countess Marya Zaleska or Dracula’s daughter (Gloria Holden)—has made off with Dracula’s corpse.

She did this to burn the thing and somehow free her from the the personal discomfort of being a vampire. It’s a nice idea, but it fails to produce the desired result. That’s not a great surprise with her hulking servant Sandor (Irving Pichel)—who likes her the way she is—working over time to badger her mind into vampire mode in a terrific scene early in the film. Pichel is remarkably sinister throughout, but never more than in this scene. (It’s no wonder that Rouben Mamoulian refused when Paramount wanted Pichel to star in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, telling them, “This guy could only play Hyde.”) This is where the film really gives him his big moment in the proceedings.

Well, as things work out, Countess Zaleska has become part of Lady Esme Hammod’s (Hedda Hopper—yes, the gossip columnist) circle of tame social lions and there she meets Garth at a party. (Where she gets to say, “I never drink…wine.”) Listening to his Von Helsing stories and his believe that psychiatry can overcome any form of obsession, she decides to give it a try. The attempt results in the film’s most famous scene where she vampirizes a young girl (Nan Grey)—a moment that is ripe with a lesbian undercurrent, though I guess it’s more bi-sexual, since Zaleska soon sets her cap for Garth, creating an interesting triangle that leads to the film’s climax.

The finale is rich Universal gothic horror at its best. Zaleska and Sandor kidnap Janet (Churchill) and fly her to Transylvania. Naturally, Garth charters his own plane and follows. “Stop him! He’s going to his death!” exclaims Von Helsing, prompting the head of Scotland Yard (Gilbert Emery) to charter them a plane. It all ends with a great showdown at the very atmospheric Dracula castle—and in a manner that sort of proves the whole vampire thing as Von Helsing’s explanation. Well, he’s been allowed to get out of England anyway, so he can probably take advantage of that. Really, as sequels go, it’s probably only second in quality to Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

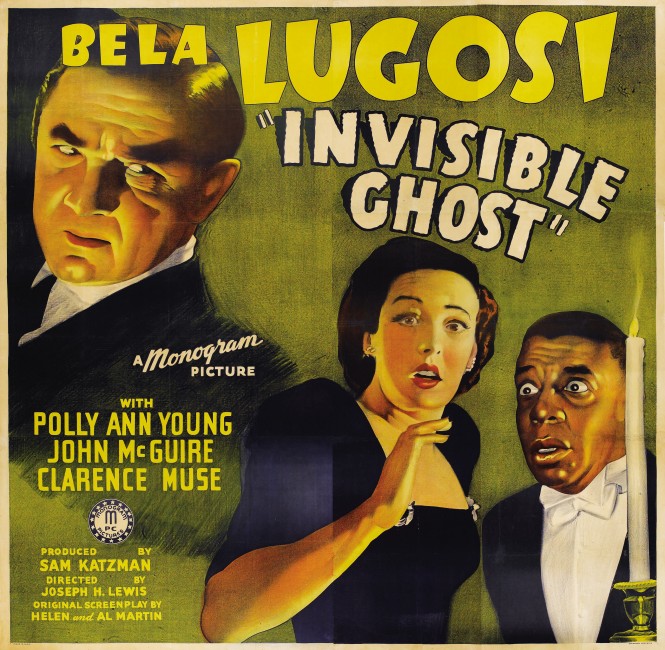

Invisible Ghost (1941). Here we get to the junk. There is some genuinely good horror from the 1940s, but for me it’s the decade of trash masterpieces—even if masterpiece is loosely applied here. Most of my 1940s choices were shot in a week or under, cost about a buck and a quarter, and were considered successful if they made a thousand dollar profit. My first two choices were produced by the legendary Sam Katzman—a man who was openly contemptuous of his audience. He once commented that there had to be something mentally defective about people who went to his movies. I’m taking the Fifth Ammendment as concerns commenting on that.

The big thing Katzman had going for him was Bela Lugosi. Katzman offered the actor the one thing the big companies would rarely give him by 1940—star billing and a large role. In a way, it was a break for Lugosi. And it gave us what I tagged years ago as “The Monogram Nine”—nine Lugosi pictures of which eight are prime Bela. Most of them, however, are indefensible on any other level. Well, maybe not indefensible, but you have to work at it.

The first was Joseph H. Lewis’ Invisible Ghost—and it’s almost a good movie. (Katzman made sure that never happened again.) Okay, so the screenplay often makes little sense. The idea is that Lugosi is a nice guy named Charles Kessler (the family must have changed their name), whose wife ran off years ago with another man, leaving Kessler with their daughter Virginia (Loretta Young’s oldest sister, Polly Ann Young, who called it a day after this). Kessler hasn’t entirely accepted this and is acting out their anniversary dinner at an empty dining room table when the movie opens. The scene manages to be both alarming and somewhat charming—maybe because everyone else seems to be taking it so matter-of-factly.

All that is fine. Harder to buy is the idea that Mrs. Kessler (silent star Betty Compson in the twlight of her career) didn’t make much of a getaway. The car she and the man she was running off with crashed and he was killed, but she was left a dazed half-wit and was picked up by Kessler’s handyman, Jules (Ernie Adams), and has been kept for years in a subterranean room in some outbuilding. Jules takes care of her and steals food from the Kessler kitchen for her. (How does no one know anything about this car crash?) All well and good—if pretty high on the preposterosity scale—but Jules doesn’t lock her in and she’s prone to wandering around and peering in at windows where Kessler gets one look at her, goes into a trance, and trundles off to kill anyone he comes across. Alright, so now it’s becoming a little hard to swallow.

We see this in action with the new maid, who, unfortunately, happens to have had an apparently pretty rooty-tooty relationship with Ralph Dickson (John McGuire), who is practually engaged to Virginia. On the flimsiest circumstantial evidence imaginable, poor dumb Ralph is sent to the chair, but worry not, his lookalike brother, Paul (same bland actor who also wears his trousers nearly to his armpits), is soon back from South America to fill the gap. (No one seems to find it peculiar that he just seems to pick up Ralph’s relationship with Virginia.) More murders ensue, of course—along with a couple of near misses—before this sorts itself out.

On the plus side, Lugosi is very believable and likable as Kessler. It’s perhaps the most purely human role of his career. His scenes with his butler, Evans (the great Clarence Muse with whom Lugosi had become friendly in 1932 on White Zombie), are charming—and Evans is one of the few completely undemeaning black characters in that era. Lugosi is also quite warm with his daughter and most of the characters. And what other movie affords him the chance to say things like, “Why, I never tasted anything to equal that roast beef,” and, “Apple pie! My! That will be a treat!”? On the downside Lugosi-wise, there are the trances. Lugosi goes into his trance several times in the course of the film and, I have to admit, it’s funnier every time.

The direction by Joseph H. Lewis is incredibly creative and atmospheric for the budget. Of course, one of the nice things for working for somebody like Katzman was that it mattered little what you did as long as it was cheap and it came in on time. So Lewis could be as arty as he liked—and he liked it a lot with his clever angles, his focus-shifts, his use of shaved-sets so he could move the camera “through” walls, etc. Of course, he was up against a pretty wayward plot, but he did a swell job with what he had, which pretty much came down to his own talent, Lugosi, and Clarence Muse. That’s more than most povert row pictures had—and even quite a few A pictures, for that matter.

(As an aside: I once owned the six-sheet pictured at the top of this entry. I paid $20 for it in 1978 and sold it for $1300 in 2000. I was sorry to see it go, but it needed restoration work and who has room for something that’s 81 inches x 82 inches? I could never afford to frame it, but it got tacked to quite a few walls over the years, so I got the good out of it. That actually could be mine restored, because there’s some apparent work above Polly Ann Young’s eye and it needed it.)

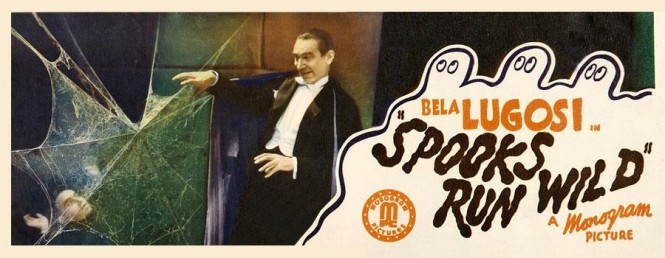

Spooks Run Wild (1941). Oh, alright! Phil Rosen’s Spooks Run Wild—which entered the world just in time for Halloween in 1941—is rubbish. It pits Lugosi—and his sidekick midget Angelo Rossitto—against Leo Gorcey, Huntz Hall and the East Side Kids. Lugosi plays a magician named Nardo who the Kids—none too surprisingly, considering the way he acts and dresses—think is a vampire when they wind up in the old dark house he’s renting. There’s also some homicidal maniac known as “The Monster Killer” (which sounds like he kills monsters) on the loose to provide some real menace.

It’s impossible to make any rational case for this one, but I like the fact that it’s a pure personality vehicle with Lugosi doing Lugosi-like things for no very good reason—except to add to the atmosphere. And it sometimes actually works, especially if you’re a sucker for old dark houses, secret passages, and Lugosi prowling them in a dinner suit. A thick layer of the old Abe Meyer library of canned music—plus, Milan Roder’s chase theme from The Black Room—applied thickly by musical directors Lange and Porter helps, too.

But bear in mind, this is Lugosi and the East Side Kids (a more civilized version of the Dead End Kids or a less civilized version of the Bowery Boys, despending on how you look at it). This is not to be undetaken lightly or ill-advisedly. Let us just say, you’ve been warned.

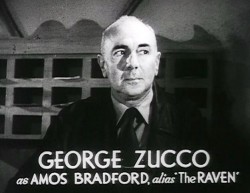

The Black Raven (1943). Murder, mayhem, and a moosehead (I think it’s a moosehead) on a stormy night at The Black Raven (Amos Bradford, prop.) is what Sam Newfield’s The Black Raven is all about. And since Amos Bradford is played by George Zucco, well, it’s pretty hard to resist. If Bela Lugosi was King of the B’s, then Zucco was certainly the Crown Prince of the C’s. His poverty row stardom was spent at PRC Pictures, which were a step down from Monogram (roll that around in your mind for a bit). And PRC let him prove that—five times. This is my favorite of them. That said, I think a good case can be made for the others. Well, Fog Island not so much maybe.

The Black Raven is a sort of remake of an even cheaper 1936 movie called The Rogue’s Tavern, which definitely does have a moosehead. It also has very little atmosphere, since after establishing the fact that it’s a stormy (albeit rain-free) night, the idea is just dropped without any explanation. Plus, it’s about 10 minutes longer for no very good reason except pacing, an out-of-nowehere revenge motive, and a supposedly killer dog. Turns out the dog didn’t tear out anyone’s throat (a remarkably blood-free affair) and that the killer has a hand-puppet of a wolf’s head—a very small head at that—complete with a set of false teeth. (Now that’s a nice touch The Black Raven might have kept.) And silent star Clara Kimball Young (her role, complete with dumb sidekick, was reworked into Zucco’s) gets a nicely hammy mad scene—in front of ca. 1919 publicity photo of herself. (See photo.)

What we have here is a group of folks stuck for the night (washed out bridge) in a storm somewhere near the Canadian border where the only accomodations to be found are at Amos Bradford’s Black Raven. This is usually an uneventful place presided over by Bradford and his dim-bulb servant Andy (get it? Amos and Andy?) who’s played by Glenn Strange with limited comedic skill. Bradford is also known as “The Raven” is a man with a criminal past that’s out to catch up with him in the person of murderous Whitey Cole (I. Stanford Jolley). Even now, Bradford doesn’t mind augmenting his income by “smuggling a hot guy across the border,” which is why another loiterer is lurking about. Everybody else who shows up are victims of the weather. Everyone has a secret or two and soon there’s a murder and a requisite dumb sheriff (Charles Middleton).

The things that make the film a treat are pretty standard. There’s a nice atmosphere, a generous dose of Abe Meyer library music (here applied by David Chudnow), and a nice supply of sinister skulking. What sets it apart from the crowd, though, is Zucco’s magnificently sarcastic performance. I don’t think there’s a single line in the film that he doesn’t turn into something to amuse himself. This ranges from the patently insincere muttering of, “Oh, that’s too bad,” upon hearing of the murder of a singularly unpleasant character to the openly insulting, “You’re more stupid than usual tonight, Sheriff.” Should you ever feel compelled to check this out for yourself, look for the Roan Group DVD—where it’s teamed with the Lugosi Monogrammer Black Dragons (1942) and Edgar G. Ulmer’s overrated Bluebeard (1944) with John Carradine. Every other copy I’ve seen is almost unwatchably dark.

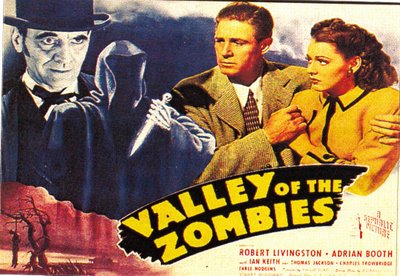

Valley of the Zombies (1946). Here’s an oddity from Republic Pictures that comes right at the end of second wave of horror. Republic only made a handful of horror pictures—all of them are unusual and none of which are without interest. This one is by a director—Philip Ford—whose name and work mean nothing to me. It runs a brisk 56 minutes and has no bonafide horror stars. Actually, it has no bonafide stars of any kind, though there are some nice character actors like Thomas Jackson (as a detective as usual), Charles Trowbridge (as a doctor as usual), and especially Ian Keith in an unusual role with an irrestible name. He plays Ormond Murks, deceased mortician and living dead mad man with a taste for blood.

The film tends to get a good deal of crap for its lack of zombies, which is only kind of reasonable, since zombies were only loosely defined in 1946. There is, however, no valley, though Murks does claim that that’s where he learned the secret of immortality. It’s really Ian Keith—contender for the role of Dracula back in 1930—who makes the film so darn much fun, even if he does seem to be channeling Lionel Barrymore at his hammiest (at least vocally). But this is a role that cries out for over-the-topness, especially given that the dialogue given him by writing partner brothers Stuart and Dorrell McGowan (who mostly wrote the kind of western called “cowboy pictures”) is very purple indeed. He comes into the film and almost his first line is, “I’m a strange man, doctor.” He very soon announces, “My wants are very simple, doctor—blood.” It stays in this tone throughout.

OK, so Murks is more vampire than zombie. Well, so what? He’s still fun. And the movie is admirably straightforward and fast-paced. It’s largely made out of cliches, but everything is done in such good humor that it seems just plain mean-spirirted to complain about any of it. Really, how can you not love a film in which the heroine (Lorna Gray) calls out, “Have you got him?” to the cop in the next room of an old dark house, only to have Murks come out and tell her, “Yes, my dear, I ‘got him”? I can’t at any rate. Unfortunately, this—and most, if not all of the Republic horrors—is not on DVD. My pretty lousy copy is from a bootleg VHS, but it’ll do for the moment. Well, there’s not much choice, come to think of it.

Night of the Demon (Curse of the Demon) (1957). So let’s end up with Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon—which was originally cut from 95 to 83 minutes and retitled Curse of the Demon for U.S. consumption. Even in that form, it was a pretty terrific movie. In its complete form, it’s even better. I would, in fact, go so far as to say that this gets my vote for the best horror movie ever made—or at least my favorite. I hasten to add that when I say that I mean horror movie that has no other agenda than to be damned creepy and scary. In other words, it doesn’t intend to be anything but a horror picture. Some works—The Black Cat, Bride of Frankenstein, etc.—completely transcend genre boundaries, but within those boundaries Night of the Demon is the bee’s knees of horror. Since I reviewed it a little over a year ago, I’ll simply direct you to that for more: www.mountainx.com/movies/review/night_of_the_demon_curse_of_the_demon

I tried showing seven 12 year old boys SUSPIRIA last night. My wife made me take it out.

I tried showing seven 12 year old boys SUSPIRIA last night. My wife made me take it out.

I’d have done the same as she — on the grounds of good taste.

Sounds better than TCM, plus THE MUMMY has that immortal line: “He went for a little walk!”

I’d have done the same as she — on the grounds of good taste.

Remember this is the age group that likes Johnny English.

Sounds better than TCM

It’s all too new — relatively speaking. And way more Hammer than I can deal with in one sitting.

Remember this is the age group that likes Johnny English.

The idea is for you to elevate them.

I don’t have a lot of free time, but I think I’m going to go with Night Of The Demon, The Black Cat and Fall Of The House Of Usher tomorrow evening. For me it isn’t Halloween without Vincent Price.

I don’t have a lot of free time, but I think I’m going to go with Night Of The Demon, The Black Cat and Fall Of The House Of Usher tomorrow evening. For me it isn’t Halloween without Vincent Price.

I have never quite been able to warm to Price except in passing. I’m not sure why, but the fact that you’ve got Night of the Demon in there and what I presume to be the 1934 Black Cat, you’re alright by me. The Black Cat would be on my list, but it’s a film I see so often — at least a couple times a year for 35 years (my first bootleg 16mm copy dates back to that) — that I didn’t want to drag it into this. Ditto Bride of Frankenstein.

TCM is playing Repulsion tonight at 4am

There’s only one Black Cat as far as I’m concerned.

BTW, Valley of the Zombies is on Netflix instant play.

TCM is playing Repulsion tonight at 4am

Estimable as the film is and much as I like Polanski, this just ain’t a movie that sez Halloween to me.

There’s only one Black Cat as far as I’m concerned.

On this, I believe we concur.

Valley of the Zombies is on Netflix instant play.

Interesting, but I’ve never gotten into the instant play idea. I would love a good copy, though. But that wouldn’t get me one, would it?