I suppose one is supposed to be in a reflective frame of mind at the end of a year, but I think this year the reflection process has been ramped up by virtue of the death of film historian and collector Forrest J Ackerman at the beginning of December. In deference to Uncle Forry — as he was known to his fans and admirers — I suppose I ought to say that Prince Sirki came to claim him on Dec. 4 of this year. Prince Sirki is the name of the man Death impersonates in Mitchell Leisen’s Death Takes a Holiday [1934], and it was Forry’s stock euphemism for death in the pages of his Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine for as long as anyone can remember. (It just this moment occurs to me that there must have been a number of aspects of that publication that were largely incomprehensible to anyone outside of fandom!)

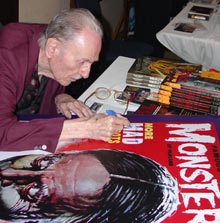

Now, Forry was 92 and his death wasn’t unexpected, but even when you’re expecting a thing like this, you’re never as ready for it as you think. I should note for the record that while I knew Forry Ackerman, I could in no way describe myself as a friend of his. We met several times at horror movie conventions and it somehow seemed to keep happening that I’d end up sitting next to him at the dinner outing traditionally arranged by Richard Valley, the publisher of Scarlet Street magazine — and who had his rendezvous with Prince Sirki last year. (This is getting grim.)

I remember the first time this happened and Forry asked me who I was. I told him. A few exchanges clarified that he knew my writing and that I’d also had a run-in with his arch nemesis, Ray Ferry. All in all, though, I was a little awkward with Forry, especially in his last years because he seemed so frail and often a little … well, out of it. I suspect he was neither, but that he found both useful for getting some peace at conventions. At the penultimate such dinner I had with him, Forry gave all the appearances of being totally oblivious to a conversation about the rumor that Ray Ferry had suggested the two of them put their differences behind them and enter on some joint venture. In a momentary lull, Forry looked up from his plate and announced, “The devil will be handing out Eskimo Pies in hell before that happens,” whereupon he returned to his dinner with impeccable timing.

By now, you’re doubtless wondering what all this has to do with critical faculties. The answer is that it has everything to do with them — and nothing whatsoever.

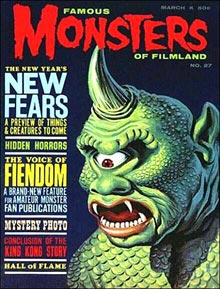

Like many cineastes of my generation — and a few that came afterwards, too — Forry’s Famous Monsters of Filmland was my true introduction to the horror genre and, by extension, to the movies in general. Oh, I’d bumped into horror movies prior to that fateful Sunday evening — following our weekly excursion to Morrison’s Cafeteria—at the magazine rack in the Rexall store when my father handed me a copy of Famous Monsters and asked if I wanted it. (He regretted this till the day he died, I’m sure. If there’s an afterlife, he likely regrets it now.) I’m aware that I’d seen Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959) in the theater and Scared to Death (1947) and Terror in the Haunted House (1958) on TV, but this was different. This was a whole magazine devoted to the genre known only to my father as “monster movies.” I was hooked at first sight — or at least first read — as much on the idea that anyone would write about movies as anything else.

As an introduction to horror … excuse me, monster movies, a kid couldn’t ask for anything better. It was nothing less than an all-you-can-eat buffet of genre pictures. But — and this is all too often forgotten, played down or simply overlooked — it had the same basic limitations of the buffet approach in that it was pretty indiscriminate. If those who put the magazine together actually recognized any difference between the intrinsic merit of James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and Christy Cabanne’s The Mummy’s Hand (1940), they kept that recognition out of the pages of the magazine.

Critical analysis was all but unknown and a great deal of the writing consisted of little more than plot synopses and fannish gushing over the greatness of Messrs. Karloff and Lugosi — with side excursions into the subordinate greatness of Lon Chaney, Jr., Peter Lorre, Vincent Price, Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee — not to mention Forry’s time-honored proclamation, “Lon Chaney Shall Not Die!” This last referred to Lon Chaney, Sr., not his less revered son, who was still alive at the time. And while few of us at the time had even seen more than a few excerpts from Chaney’s movies on TV, we accepted this at face value in a kind of “Forry said it, I believe it, that settles it” fashion. Plus, there were those tantalizing photos (mostly from Forry’s collection) of Chaney in various exotic and/or horrific make-ups. Who could doubt his greatness? For that matter, who wanted to?

In hindsight, I believe that this was a plus rather than a minus in that it allowed our young minds to sample at least a bit of everything that became available to us without prejudice. Call it Free Will Film School. You got to make your own calls on the quality or lack thereof with any given film. Of course, when you’re 10 there’s every chance that you’ll be just as happy watching a crap-fest like The Mummy’s Curse (1945) as a seriously great film like Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Black Cat (1934)—and maybe more so, since the former has your actual monster in it, while the latter is more psychological in tone. Similarly, the idea that Louis Friedlander’s The Raven (1935) might be inferior to The Black Cat was just silly. They’re both Boris Karloff-Bela Lugosi pictures made at about the same time for the same studio. When you’re 10 that’s enough.

I can’t speak for everyone, but in my own sphere what we first concluded was this — any movie made between 1931 and 1945 (that encompasses the two waves of the “Golden Age” of horror) was probably worth watching. Any film from that era festooned with the Universal airplane or the lucite Universal globe with the twirling stars was generally better than any movie that wasn’t. Considering that the “Shock Theater” TV packages were put out by Screen Gems (“a subsidiary of Columbia Pictures”) and consisted almost entirely of old Columbia titles and similarly vintage Universal products, this wasn’t a terribly well-reasoned call. It was, however, the beginning of a more critical-minded approach to the movies. Crude, yes, but it was a step.

As limited as this Universal-centric approach was, it did have the advantage of working as an ice-breaker to other genres. Without that lucite globe what would have possessed me to tackle W.C. Fields in You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man (1939), Deanna Durbin in Three Smart Girls Grow Up (1939) and John M. Stahl’s classy soaper When Tomorrow Comes (1939)? And there were pitfalls, too. Did I really sit through a 1933 college football movie with Robert Young called Saturday’s Millions just because it was preceded the Universal plane flying around the globe? Sadly, I not only did, but I can still recall a line of dialogue from it. (At one point, Young flirts with Lelia Hyams by asking, “You hasn’t any wood you want chopped, has you, lady?” I even tried it on a girl once. Maybe it works better in a climate other than the one found in Florida.)

Somewhere along the way, though, the Universal playing field started looking a little uneven. It’s hard — even in one’s youth — not to eventually notice that there’s a difference between Frankenstein (1931) and The Mad Ghoul (1943). (Having it pointed out that a British critic of the era had remarked, “Being a ghoul would seem to be disconcerting enough. Being a mad ghoul must be the height of personal embarassment,” helped validate that realization.)

This really fell into place one night when watching a double-feature of Lambert Hillyer’s Dracula’s Daughter (1936) and Roy William Neill’s Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943). Both horror pictures, both with iconic monsters, both from Universal, both running just a little over 70 minutes—and I’d seen both lots of times. But something was different this round. Dracula’s Daughter zipped along and was as entertaining as one could wish. Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, on the other hand, plodded along at what seemed an interminable pace. Good Lord, not only were all Universals not created equal, some of them were just plain not good. (Don’t laugh. I know people my age who haven’t been able to admit this yet.)

It was about this same time the penny dropped in the slot on another front — namely was there perhaps some connection in between how different and how much better than most of the others Frankenstein, The Invisible Man (1933) and Bride of Frankenstein and the name “James Whale?” After all, these three movies all bore the phrase “directed by James Whale.” I had little — probably none at all — idea of just what a director did, but there was something identifiable, something unique about these films. Plus, Whale was clearly somehow special. All you had to do was watch his credit on Bride of Frankenstein where his name come flying forward, hitting the screen with a resounding clash of cymbals on the soundtrack. He must have been important to warrant that.

I put it to you plainly — it is from this sort of dim awakening of reason that auterist film critics are born. The world is still divided as to whether or not such persons should be put to sleep at the first hint of auterist tendencies. For those who don’t worry about these things, subscribers to the “auteur theory” (blame all this on the French New Wave and Andrew Sarris) work on the basic concept that the director of a movie is, for all intents and purposes, the person responsible for the film overall — its author. It’s a very good theory, but it has limitations. (We’ll get into that some other day.)

The problem with this revelation was that it kind of produced a “so what?” feeling. Andrew Sarris was a few years away from publishing The American Cinema, which would have at least explained the concept behind my suspicion — or I should say our suspicions, because I had friends who were also coming to similar conclusions. We knew the Whale pictures were funnier (deliberately) than the others, that the camera moved around in much more elaborate ways, that Whale was always tilting his camera to produce odd angles, etc. We knew all this was neat, but it went no deeper than that. And nothing we were reading suggested that there might be anything deeper—if it admitted to Whale more than in passing. At that time, everything was focused on the stars, not the directors.

This was to change a bit when we discovered Calvin T. Beck’s Castle of Frankenstein, a magazine that offered a somewhat more adult take on the horror genre. The magazine had been around since 1962, but its distribution was less pervasive than Famous Monsters, and the output more spotty. I’m not sure if it actually had a publishing schedule. It just appeared every so often on magazine racks — more or less to our delight. I say “more or less” because actual criticism is more prickly than what we’d been used to — even when, or maybe especially when, it was right.

One thing that set Castle apart was the section that included mini-reviews of movies (often wandering past the genre realm) that were in many cases terse dismissals, penned (at least in part) by future director Joe Dante. I remember my ire when one of these reviews refered to that undisputed classic of cheese-paring fun The Ape Man (1943) as a “grade C Bela Lugosi vehicle.” How dare he? Worse, how dare he be right? That was the kicker. It’s not easy seeing your youthful enthusiasms put into a different perspective, and it’s worse when you see the validity of the argument. Still, it opened the door to a more in-depth approach to considering movies — how they worked, why they worked, why they didn’t work, and who was at the bottom of all this.

It’s easy to say that all this was worlds away from Forry Ackerman and Famous Monsters, but the question arises as to whether many of us would have arrived at this point without “Uncle Forry’s” magazine? This has been debated for years in fandom — especially by those not in sympathy with Forry, who like to put forth the idea that if it hadn’t been for Famous Monsters something else would have come along to perform the same function. That may or may not be true. It has the advantage of being an untestable theory, so it suits those who want to believe it. Personally, I’m skeptical — not in the least because the tone of Forry’s mag was unique and uniquely suited to younger fans.

But more, I think we all benefited from its largely uncritical approach to these old movies. It encouraged us to try everything in a way that the more critical Castle of Frankenstein didn’t. That all-encompassing approach is exactly what made my temper flare when I saw The Ape Man reduced to “grade C Bela Lugosi vehicle.” Even though that’s a pretty fair — if shortsighted — assessment of the film, the very fact that we weren’t prepared to accept that judgment as definitive is something I find healthy. It’s also something I attribute to an early childhood steeped in Forry’s approach. By not loading us down with what was good and what wasn’t, we were left to judge for ourselves. That was perfect for the age group. By the time we wanted something “more,” we didn’t blindly accept the judgments we encountered as fact. Left to our own devices, we’d started to figure some of this out for ourselves.

What followed was much more complicated. Some set it all aside. Some made it into a hobby. Some embalmed it all in a childhood they never let go of. A few of us made something like careers out of it. The level of criticism changed. The kind of things we read changed, while what we wrote was very different from what we’d been raised on. But it happened by almost imperceptible degrees, and it all still goes back to those youthful introductions. And for me at least, it all centers on Forry Ackerman—even if I “outgrew” him years and years ago. Or did I?

Back in 1998 when I first had an encounter of any kind with Forry, issue no. 30 of Scarlet Street had just come out. It contained a very long, very detailed analysis of Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein that I’d written, and of which I was reasonably proud. (I still am, by the way.) After the fact, I heard from publisher Richard Valley that Forry and his right-hand-man Joe Moe (the most genuinely sweet human I’ve ever met) had spent a large chunk of their flight back to L.A. reading the article and discussing it. I really wasn’t prepared for this somehow. The idea that Forrest J Ackerman — the grand old man of fandom — was now reading something I’d written (and reading it approvingly) was almost unthinkable to me. And it mattered to me far more than I could ever have imagined, carrying me back to that first issue of Famous Monsters on that drugstore rack 35 years earlier. I hadn’t so much outgrown Forry maybe as I’d merely carried on the example he set and made it my own.

Looking back on it all now — and the slow development of a critical sensibility — I’m shocked to realize that the “old movies” that started all this were in many cases a lot less old than contemporary movies I grew up with. When I first read about The Phantom of the Opera, it was 38 years old. That means it was less bewhiskered then than, say, A Hard Day’s Night is now at 44 years old. Good heavens, what a sobering thought that is. It makes me understand that to Forry, these old movies didn’t seem old at all — and that was probably the key to it all, to the enthusiasm. And, yes, it also makes me feel old. Tell me, do they still make Geritol? I think I need some.

The last paragraph made me laugh. A few days ago I was talking with my girlfriend telling her I was about to watch Seven (catching up on my Fincher before Benjermain B.) and she said it was an old film. I said not really, its about 12 years old, and she said uh thats old. Which made me think, geez youre not a film nerd are you? By the way it must been really sweet meeting one of your influances, I hope one day to possibly meet p.t anderson and dream on how cool itd be if he commented on a film I made.

I was wondering when Ackerman’s passing would get a mention by you. It was clear from reading your reviews, beginning when I moved here in 2001, that you were probably 8-10 years older than me. Just the ripe age for the early 60s shock theatre boom and the debut of Famous Monsters Of Filmland. This was confirmed upon attending viewings of films with you in the audience.

After reading every horror film review of yours jacked up a star or two more than I would ever consider, I figured you were at an impressionable age when first exposed to FM. Me? I was busy being conceived when FM debuted, so horror never got its meathooks (so to speak) in me. I didn’t pick up an issue of FM until I was all of 16 in 1978. One was enough. After all, Starlog had been in print for a few years by that time!

I was indifferent to horror and fantasy but sci-fi got a hook in me from being bored out of my mind in the South Carolina low country on vacation and reading my uncle’s issues of Analog and F&SF;. After then trying a few sci-fi movies (previously I had lumped sf, horror and fantasy together as not my cup of tea) the latent graphic designer in me thrilled to one indisputable fact: every item in front of the lens was an art directed prop that had to be designed by someone! By the time Star Wars debuted, I was incredibly moved by the industrial design of the Death Star interiors! Flash forward 30 years and I’d sooner put a loaded gun in my mouth than watch any movie loaded with effects; reserving particular scorn for those with computer graphics! The last science fiction film I’ve bothered to watch was the subdued and compelling Gattaca. But I digress.

Ackerman was one of the prime alpha geeks and had a house full of neat stuff he was all too happy to share with anyone who dropped in. How could you not love that?

While on the subject of the Shock Theatre boom, were you a watcher of Dr. Paul Bearer’s Creature Feature on WTOG-44? I remember when cable TV came to South Orlando in the late 70s. The first neighborhoods to get it were the older ones with telephone poles. My friend Dave had it and the best reason to get cable was WTOG being carried so one could see Dr. Paul Bearer! When my area finally got cable a year or two later, we had about 2 months of channel 44 before a lineup change in basic cable which saw WTOG being dropped. Sonnuva…! Dick Bennick was a pretty long lasting horror host. He carried the torch long after the boom faded in the late 70s. I was saddened to see his widow put the kibosh on any repeats of his program. What a loss for future generations.

she said it was an old film. I said not really, its about 12 years old, and she said uh thats old.

You know, a Krishna salesman once did himself out of selling me a set of volumes on the religion by refering to what was on TV “as some old movie.”

I hope one day to possibly meet p.t anderson and dream on how cool itd be if he commented on a film I made.

Not impossible. I have actually had just that experience, only the filmmaker was Ken Russell. It still seems pretty unbelievable to me, but then I also remember the speech I made about him in 2005 when giving him his Lifetime Achievement Award at the Asheville Film Festival. He had been brought up onstage before he was supposed to be, so I made him stand there and wait for me to finish (“What are you doing here? I’m not finished enthusing about you yet”). I got to the part where I was talking about first seeing Tommy and remarked, “If anyone had told me then that one day I’d be up on a stage presenting an award to this man, I’d have said they were crazy.” He then leaned in to the microphone and said, “And well you ought to have done.”

I was wondering when Ackerman’s passing would get a mention by you.

To be honest, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to get into it because I didn’t want it to feel like I was cashing in, and I certainly didn’t want to give the impression that I was a really close friend of his.

After reading every horror film review of yours jacked up a star or two more than I would ever consider, I figured you were at an impressionable age when first exposed to FM.

Oh, yes, that’s true enough. At the same time, this is perhaps also why I can be a lot harder on horror films I don’t like.

I didn’t pick up an issue of FM until I was all of 16 in 1978. One was enough.

I should hope that one would have been enough by the age of 16! I’d long bailed on the magazine by 16 — and to some degree on the genre, having discovered film historians like William K. Everson (who was also a horror fan) and the delights of 1930s Paramount movies (which I hope I never grow out of in the least!).

Ackerman was one of the prime alpha geeks and had a house full of neat stuff he was all too happy to share with anyone who dropped in. How could you not love that?

And there, I think, you’ve summed up the essence of the man — his generosity of spirit.

While on the subject of the Shock Theatre boom, were you a watcher of Dr. Paul Bearer’s Creature Feature on WTOG-44?

Hell, I knew Dr. Paul Bearer when he was just Dick Bennick, working for a top 40 AM station (back in the days when AM radio played music), WGTO in Winter Haven. (The station was actually on the road where he had the accident that left him with one eye.) I was actually a little old for Paul Bearer, but I watched him and delighted when he would do something really esoteric like lip-synch Tom Lehrer songs. I wrote about him in passing in one of these columns…oh, it’s this one —

http://www.mountainx.com/movies/screening_room/2008/cranky_hankes_screening_room_the_pleasures_and_perils_of_fandom

And I see it’s very in passing. I spent some considerable time with Bennick one afternoon during my days as a photographer, since I’d been hired to photograph a hamster race that he’s been hired to judge. I’m pretty sure he got paid more than I did, but I didn’t have to wear make-up, a costume or drive up in a hearse. I met him a few other times at similar, albeit less memorable, functions.

Great article. I wasn’t allowed to have these magazines, but I devoured many issues at the magazine rack, waiting while my mom was shopping. I mentally cataloged hundreds of films that I wanted to see, many not until recently.

I think it’s hard for younger people to fathom the fact that the only resource that a kid had for movies was the theater and television. I had to wait YEARS to see a movie!

Also noteworthy to cult movie fans is the passing of SLEAZOID EXPRESS editor Bill Landis, who lovingly covered the heyday and decline of grindhouse theaters.

I wasn’t allowed to have these magazines, but I devoured many issues at the magazine rack, waiting while my mom was shopping.

I went through periods — usually caused by some well-meaning friend of the family, who thought this stuff was unwholesome — where I’d be threatened with the prospect of having everything thrown out, because I had become “morbid.” Somehow this never got past the threat stage. I think once the pictures cut from the magazines came down from the closet door, but didn’t get tossed.

I think it’s hard for younger people to fathom the fact that the only resource that a kid had for movies was the theater and television. I had to wait YEARS to see a movie!

Well, I go back further than you, Marc, so I can up the ante to living in a town with one movie theater (in those days they changed the bill twice a week) and, for a long time, being limited to four TV stations. True agony was poring over the listings in the TV Guide and finding some hotly desired title — only to find it was on some station you couldn’t get. I remember once trying to convince my parents that we needed to go spend the night in Fort Myers so I could see something on channel 11. They didn’t go for it.

When I was a kid, I collected every issue of FM (although I did not start buying them until around 1960, a couple of years after it began publication). I had every issue from #1 on until I outgrew the magazine (probably around 1967 or 68). I sure wish I had them all now!

In any event, FM (and some of its competitors) were eagerly anticipated purchases, and I would pour over every word and image. I was always tantalized by references to films I’d never seen or heard of (and I saw every horror and sci-fi film that came down the pike during those years). Many of us remember Famous Monsters of Filmland fondly as an intrinsic part of our childhood. Thank you for remembering Forrest J. Ackerman, and for this interesting article.

When I was a kid, I collected every issue of FM (although I did not start buying them until around 1960, a couple of years after it began publication). I had every issue from #1 on until I outgrew the magazine (probably around 1967 or 68). I sure wish I had them all now!

I never had anything like a complete set — and as indicated above, I had a bad childhood habit of cutting the pictures out of them as “closet door art” — and I absolutely cannot recall when I stopped buying them. It occurs to me that I may have had the complete run of Monster World or whatever the short-lived sister magazine was. As for wishing you had them now…well, I shelled out $40 for a copy of no. 27 on eBay about 9 years ago, so I can only imagine what a complete set might be worth.

Nice tribute to Forry, Ken, and a good overview of the evolution of critical thinking. Like yourself, I inhaled FM uncritically (and George Adamski’s “flying saucer’ books, but let’s not go there) but eventually came to see that many of the things that interested me were not of equal quality. This started somewhere between the ages of eight and thirteen: At the former age I had the bejeezus scared out of me by the “ghosts” of Carnival of Souls; at the latter age, I realised, “Hey, they’re just people in white makeup!”

At the former age I had the bejeezus scared out of me by the “ghosts” of Carnival of Souls; at the latter age, I realised, “Hey, they’re just people in white makeup!”

That’s one of those key moments that can either make it or break it for people — depending on mindset. You either reject it all as artifice, or you marvel at the fact that it is artifice and yet it still works. (I mean this is broad sense and not specifically as concerns Carnival of Souls, about which I’m kind of ambivalent.)

…the filmmaker was Ken Russell. It still seems pretty unbelievable to me, but then I also remember the speech I made about him in 2005 when giving him his Lifetime Achievement Award at the Asheville Film Festival.

I have an .mp3 of that event (thank you, Google Alerts) which I’m listening to even as I write. By the way, are you still working on the follow-up to your first Ken Russell book?

By the way, are you still working on the follow-up to your first Ken Russell book?

Theoretically, yes, but there never seems to be enough time to really do it. Either there was a lot more time when I was younger, or I had more stamina. Possibly both.

Catching up , a tad late.

Wonderful remembrance of “Uncle” Forry. And spot on.

He did open up a world of imagination to so many of us. Not only with the films. I began to read more (and yes, I think the first FM that begged me to “take me home little girl” was circa 1962). He would mention the source book for a film . I would seek it out. I may not have quite appreciated Stoker’s Dracula, or H.G. Wells or John Wyndham, at the time, but the door has been opened.

He also had a very liberal world view. He no doubt influenced my rather liberal leanings in no small way. They are those who would damn him for that alone. But I would not be one of them.

I would wager many of us who are obsessed with film owe much of our passion to a vintage copy of FM.

I have only had to replace a few copies of my collection at “collector’s” prices. As soon as the parents started making noises about tossing them, and their “bad” influences, I started hiding them. And moving the hiding spots.

He also had a very liberal world view. He no doubt influenced my rather liberal leanings in no small way. They are those who would damn him for that alone. But I would not be one of them.

Well, I’ve observed before that fandom — by which I mean horror movie fandom — is more fractured by political/sociological leanings than any other single factor. And while I’m perfectly aware of Forry’s stance as a liberal, I’d never really thought about his position in that as concerns his supporters and detractors till this minute. As I turn over in my mind the list of those who are, shall we say, unfriendly to Forry, each and every one I can name falls into the hard-right conservative category.

I have only had to replace a few copies of my collection at “collector’s” prices.

That one issue is the only thing I’ve felt compelled to track down. Little of my original “collection” still exists, but that has everything to do with me cutting the pictures out of them, and nothing to do with parental interference, which never got past the threat stage.

Forry Ackerman and FM certainly had a strong impact on my development, too, and I can well remember my first visit to his home over 40 years ago. More than a historian, though, I would call him first and foremost a collector, because I never knew him to do much in the way of original research, at least not of the sort of most film historians I have known. He also had no use for film music which, being one of my main interests, was too bad.

I had to keep from laughing when he said with a perfectly straight face that the Ennis House designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in the Hollywood Hills was where THE BLACK CAT was filmed. Maybe he was mixing it up with HOUSE ON HAUNTED HILL?

But there was only one FJA and I lift a toast to him that long shall his memory live in our hearts!

I’m sure he had mixed up HOUSE ON HAUNTED HILL with BLACK CAT… but I think with all his memories he may have been allowed a gaff.

I first met him in the flesh in the early seventies, but he took pity upon a distaff fan and was so generous for years before.

Yes, raise a glass (although he would probably not approve). He was one of a kind.

More than a historian, though, I would call him first and foremost a collector, because I never knew him to do much in the way of original research, at least not of the sort of most film historians I have known.

That’s probably a very reasonable way of looking at it. “Film historian” is such an elastic term in a lot of ways. I’ve been labelled one on occasion, and in a sense I guess that’s fair, but I’m not particularly fond of research in the sense I suspect you mean. And I have little interest in books on film that are primarily catalogues of research. I’m much more interested in critical analysis, but that isn’t something that can be said to have been Forry’s strong suit either. Collector is probably a very good term, but I think I’d made it collector/enthusiast.

Maybe he was mixing it up with HOUSE ON HAUNTED HILL?

That would certainly be my guess.