When Rob Zombie first appeared on the filmmaking scene with House of 1000 Corpses in 2003, I wrote that he was ” just a fan who’s made a film and is not actually a filmmaker.” While there’s a core of truth in that statement, it’s not one I would make today. Four Zombie movies later and a lot of revisiting and rethinking Corpses, I’m convinced that Zombie is a fan who is also a filmmaker. He’s no less a filmmaker than any of the other filmmakers out there whose films are redolent with other people’s movies. (Yes, I am looking at you, Mr. Tarantino.) This was an inevitable development as film history grew and as more and more movie generation filmmakers emerged.

The earliest filmmakers had no movie history to draw on, so their influences—and references, for that matter—came from other sources like plays, novels, paintings, operas, etc. (There was even a school of filmmaking called pictorialism—mostly associated with Maurice Tourneur and Rex Ingram—that centered around painterly composition techniques.) This didn’t last long, of course, because as soon as someone did something new (or something that gave the appearance of being new) others copied it, refined it and altered it to suit themselves. Art has always functioned in this manner. The history of art is the history of guys swiping stuff from each other. We politely call this “influence.” There’s nothing wrong with it, and it often leads to some amazing works that stand on their own merits and sometimes are better than the originals.

I’m not even going to try to go deeply into this—that’s a 24 volume dissertation sort of thing. Take an isolated and possibly unique example, though—the impact of F.W. Murnau on Frank Borzage. When William Fox brough Murnau to Hollywood, Borzage’s very concept of filmmaking was altered. Previously, he’d made films—often very good ones—on the standard American basis of a largely immobile camera. For Borzge, Murnau’s moving camera freed up his whole approach to filmmaking. The movies he made suddenly became fluid. Yet they did not become imitation Murnau. They simply adopted, borrowed, were influenced by his style. And if Borzage ever simply copied something Murnau did, he did it to his own ends. Anyway, don’t Murnau’s American films have some of Borzage’s romantic lyricism? Can we ever be sure that the two—working at the same studio and having become friends—didn’t swap ideas all the time?

It’s possible to trace influences in any filmmaker’s work—and it’s a very profitable thing to do if you’re trying to understand a filmmaker. In fact, it’s probably impossible to do so otherwise. Sure, you can enjoy the Coen Brothers without realizing the influence of Preston Sturges’ writing on their dialogue, or that the title for O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) comes from Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941), but knowing these things helps you to understand where they’re coming from. However, we’re more or less still in the realm of influence—verging on homage. There is another realm of filmmaking out there that goes beyond that.

Whether or not it’s possible to pinpoint the start of filmmakers whose works are almost entirely formed by old movies, I’m not sure. I do know that I had a long exchange with Michael Gallagher (the then head of Catholic Film Board that rated movies on their suitability for members of the Church) on this topic a good 27 years ago. His particular bete noir at that time was Brian De Palma, who work he characterized as being in touch with nothing “other than old movies.” De Palma with his wholesale borrowings from Hitchcock may indeed be the starting point, which is ironic since he’s been around long enough now that his own movies have been copied.

Even then, it was hardly limited to De Palma. Jim Sharman’s The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) is a riot of movie—and other pop culture—references. Ken Russell’s Lisztomania (1975) is not only largely built on affectionate parodies of film genres, but contains specific references to everything from Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925) (a sequence that itself includes a reproduction of the final shot from John Ford’s The Searchers [1956]) to Busby Berkeley’s The Gang’s All Here (1943) to Hammer horror movies and beyond.

Our post-modern sensibilities have made this approach more acceptable as a potentially viable art form in its own right. I’m not entirely sure I always agree with the idea, but very often the movie geek in me wins out in an artistic argument of this sort. Throw me enough nerdy in-references and I’ll be at least lulled into a state of some kind of acceptance.

Tim Burton represents something of this kind of filmmaking, as is evidenced as earl y as his short film Frankenweenie (1984), which rethinks Frankenstein (1931) in terms of childhood imagination and suburbia. There are clear movie fan references in most of his films—Metropolis (1927) in Batman (1989), Nosferatu (1922) and a host of Roland West nods in Batman Returns (1992), 1950s sci-fi in Mars Attacks! (1996), Brides of Dracula (1960) and other Hammer films in Sleepy Hollow (1999), etc. Burton differs in one respect, however, since his work tends toward an impressionistic vision of the older movies. Burton’s approach is more grounded in conjuring his memory of having once seen the earlier films rather than referencing the films themselves. The feeling is unique to his work.

Almost certainly, the most famous—and arguably best—practitioner of this kind of filmmaking in its purest (if that’s the word in this case) is Quentin Tarantino. Everything he’s made is grounded one way and another in “old” movies—and in the concept of an earlier moviegoing experience. He’s tried to fuse together the art house and the grind house (or the drive-in, which is its more rural equivalent). Once, of course, he—and his friend Robert Rodriguez—even tried to duplicate the whole sleazy, cheesy double-feature experience with Grindhouse (2007)—to the bafflement of the general public.

In Tarantino’s most recent film, Inglourious Basterds, he may have achieved something very close to the perfect blending of art house and exploitation trash. The drive-in sensibility is intact, but the references have become more sophisticated than Shaw Brothers movies and blacksploitation, etc. Tarantino’s still got his geek game on, but it’s dotted with references to—and influences of—filmmakers like G.W. Pabst, Hitchcock and Fritz Lang. Moreover, the actual echoes are more interwoven into the fabric of Tarantino’s story than before. The Metropolis-born image of a gigantic close-up of a woman’s face laughing maniacally out of the flames is so completely a part of Inglourious Basterds that the reference is almost inessential—except, of course, that it connects to the whole German film culture that fuels the plot and tone of the film.

And that brings us back to the strange case of Rob Zombie—the very strange case of Rob Zombie, who is perhaps the biggest movie geek filmmaker ever. Mr. Zombie was born Robert Cummings, an inconvenient name for a public persona since it already belonged to a light leading man from the 30s and 40s, who become a pretty major TV star in the 50s. Plus, it just doesn’t have the kick needed for a shock rocker, hence Rob Zombie.

Considering that Zombie named his band White Zombie, after a 1932 Bela Lugosi picture, it was hardly surprising to find a movie geek lurking in the shadows when he turned his hand to filmmaking with the much-delayed House of 1000 Corpses, which languished for ages at Universal (I received a presskit for it from Universal in 2001), briefly moved to MGM and finally emerged in a not-very-wide release through Lionsgate—in a version that clocked in at 88 minutes. Reports are that the original cut ran 105 minutes. Gaps in the narrative definitely suggest much is missing.

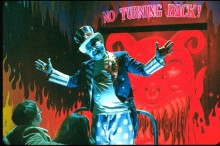

H1K—as Lionsgate insisted on calling it when I was badgering them to release it in Asheville—is a wild grab-bag of movie/pop cultural references. It recreates a “Shock Theater” TV show with a horror host. It boasts clips from James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932), George Waggner’s The Wolf Man (1941) and Erle C. Kenton’s House of Frankenstein (1944). The character names for the film’s villains are all drawn from the names of characters in Marx Brothers pictures. The atmosphere of the film—and aspects of the plot—are clearly indebted to Tobe Hooper’s Chainsaw movies, as well as his Eaten Alive (1977) and The Funhouse (1981). For that matter, Zombie predates Tarantino’s use of battered drive-in movie “Our Next Feature” transitional clips.

Other pop culture references crop up—a disconcertingly surreal sequence where Sheri Moon Zombie lip-synchs to Helen Kane’s 1930s recording, “I Wanna Be Loved By You,“and an equally disturbing use of a Slim Whitman song on the soundtrack. There’s also an obvious love for cheesy roadside attractions, spook houses and local legends. It’s a rich assortment. It’s also a mess, but it’s a mess I return to again and again out of sheer fascination. Though later films of Zombie’s are better—notably The Devil’s Rejects (2005), which is a sequel that’s rather more Tarnatino-esque in successfully replicating a drive-in movie—it has come to be my personal favorite.

What’s remarkable—and to some untenable—about Zombie’s work is that it’s even more unapologetic about its sources than Tarantino’s films. Zombie doesn’t even seem to care whether the viewer gets his references, nods and sources—and let’s face it, a lot of his audience isn’t going to—and he often doesn’t bother to actually incorporate these things. He just throws them in. Why? Well, my best guess is that he simply likes them and wants to put them in his movies. It’s almost as if he’s really making these films for himself and maybe a few friends—and he’s somehow been able to get away with it.

Perhaps his greatest affront in this realm is The Haunted World of El Super Beasto, which had a brief theatrical release right after Halloween II and is now on DVD. This is an animated film—a very R rated animated film—based on a comic book of his own creation. Zombie the film fan is front and center and in your face about it from the very beginning. The film opens with an animated Edward Van Sloan stepping out from behind a curtain on a stage and giving an appropriately modified version of the opening warning speech from James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931). Never has Van Sloan’s campy, “Well, we warned you,” had such meaning. Not content with this, Zombie duplicates the look and graphics of Frankenstein‘s opening credits and uses that film’s main title music (slightly elongated by seamlessly repeating a phrase) for his score. For an old horror movie buff, it’s a little bit of nirvana—and a laugh.

As the very strange film progresses, we find most of the characters from Zombie’s own cinematic world (it could have done with more Sid Haig, but that’s true of most things), along with the Bride of Frankenstein, the chest burster from Alien (1979), Jack Nicholson from The Shining (1980), a lovesick robot modelled after the iron man in the 1939 serial The Phantom Creeps, etc. There’s a deliciously funny recreation of the prom-and-a-bucket-of-pig-blood scene from Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976) that snags ever nuance of the original—right down to the slo-mo strand of crepe paper streamer falling and De Palma’s beloved split-screen work. There’s a sequence where an ape makes off with a girl at the behest of his master, Dr. Satan (voiced by Paul Giamatti), during which the buildings and backgrounds transform into those from Robert Florey’s Caligari-esque Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932). For that matter, there are also references to the bogus trailer Zombie made for Grindhouse, Werewolf Women of the SS. Movie geek filmmaking doesn’t get any geekier than this.

And a great deal of the film’s silly story—and some of the gags—actually work. But—and this is a very big “but” indeed—all of this really cool stuff sits right next to some of the most juvenile depictions of sex and sexuality and mammary madness I’ve ever cringed through. And believe me, I’ve cringed my way through more than my share. (OK, so Dr. Satan pleasuring himself while listening to Debbie Reynolds singinge ultra-saccharine 1950s hit “Tammy” was too twisted not to appreciate.) As a result, El Super Beasto is another of Zombie’s uneven affairs. That’s to say, it’s a lot like his other films, though not entirely in the same way. Still, it’s a rather glorious film in its unevenness—glorious, that is, in a movie buff manner. Taken that way, it’s a pretty impressive 77 minutes of nonsense served up with verve and nostalgia.

I don’t know what this film fan as filmmaker is going to lead to. Nobody does really. I have a sense that it’s going to end up being one of cinema’s many fascinating dead ends. There’s only so much to assimilate and play around with and reference before it gets old. The snarky post-modern humor and pop culture references in so many animated “family” films have already worn out their welcome—and remember how fresh that seemed a scant eight years ago when Shrek came out? But it’s here now and it seems to be flourishing in little pockets of film—from the amazing Inglourious Basterds to the amazingly odd El Super Beasto. My suggestion is to sit back and enjoy the wild ride while it lasts.

I would have mentioned Ken Russell’s influence on Baz Luhrman.

I would have mentioned Ken Russell’s influence on Baz Luhrman.

I would have if I’d brought up Baz Luhrmann, and if influence had been where this was going. While I’d be the first to admit that Luhrmann has been very influenced by Russell, and that Lisztomania in particular influenced Moulin Rouge!, but I can’t think of a specific instance where Luhrmann “quotes” a Russell film. Of course, the list of filmmakers influenced by Russell is probably greater than even some of the filmmakers know, since so much that he did in camera movement and editing has been assimilated into the general cinematic vocabulary.

Great work

28-sep-09

firestormcafe

7:30pm

I keep giving Zombie chances to wow me, but with the exception of DEVIL’S REJECTS, I’ve been unimpressed. I’ll give him another with this one.

It was if INGLORIOUS BASTERDS was made just for me, and unlike his other films, the references worked seamlessly.

I think Joe Dante is another who during his heyday was stuffing his films with homages to the past.

I think Joe Dante is another who during his heyday was stuffing his films with homages to the past.

Maybe it’s that I’ve never been able to take Dante seriously on any level that that didn’t occur to me. His work is certainly not devoid of in-joke references. I think the reason he’s not memorable and rarely works for me is that it’s too wink-wink — like warmed over Mel Brooks.

The Strange Case of Rob Zombie would be a great title.

The Strange Case of Rob Zombie would be a great title.

Agreed. Now all we need is the material to go with it.

This article inspired me to go check out your review of THE GOOD GERMAN. However, I can’t seem to find it anywhere. I remember that you pretty much hated it, but I can’t find the review in the archive. Am I imagining it?

This article inspired me to go check out your review of THE GOOD GERMAN. However, I can’t seem to find it anywhere.

Actually, I did write a review of it and I did, as you recall, pretty much hate it. However, the film never played here. It was scheduled to, but WB pulled it and so the review never ran. If I can find it, I’ll see about having it put into the archive.

House of 1000 Corpses is truly one of the most freakiest movies I have ever seen. This movie should go down in history as one of the top 50 horror movies ever. The credit is well deserved for Rob Zombie as a great horror director, let alone being called director.