I was 18 years old when I got my first dose of Betty Boop. It was at a three day film festival at the University of South Florida where cartoons and shorts had been programmed to screen between the movies. I remember the first encounter was Betty Boop, M.D. (1932)—and let me tell you, it was your proverbial love at first sight. This was just amazing stuff—like nothing I’d ever seen before. Oh, I’d heard of Betty Boop, but whatever reason she’d never been a part of any cartoon package that had come my way as a child, and at that time (1973) film history hadn’t paid much attention to animated films as more than a footnote. In many cases, cartoons were considered an almost evil development that was blamed for killing off the short film.

There were 16 features screened that weekend—some I’d seen, others I hadn’t—but I doubt it anything I encountered for the first time came anywhere near the impact of the Betty Boop cartoons. There were only three, so we’re talking about 21 minutes of screen time all told. But what a 21 minutes it was. For those who don’t know Betty Boop, only know the image of the character, or—God forbid—only know the cartoons after the production code sanitized the cartoons into a vomitable morass of treacle that bore only a nominal relation to the original. Betty is hard to comprehend. You have to see her.

There was no pretense—at least early on—that these cartoons were aimed at children. Betty—even in her earliest incarnation when they can’t seem to decide whether she’s human or a dog—is meant to be sexy. She dresses provocatively. Her skirt is very short—to the degree that when she bends over her panties are often exposed. And when that doesn’t happen, there never seems a lack of invention about her skirt being blown upwards. She wears a garter. She has cleavage and wears backless dresses that defy the law of gravity. Occasionally, her clothes fly off her altogether. And should she be wearing a long gown, it’s very sheer—often backlit so we see through it—and clings to her contours. Other characters are openly lecherous in their pursuit of her. In Boop-Oop-a-Doop (1932), the lecherous villain strokes her bare leg in his attempt to take her “boop-oop-a-doop” away. The Old Man of the Mountain (voiced by Cab Calloway) in the 1933 cartoon of the same name waggles his tongue at her obscenely. Olive Oyl she ain’t—even if Mae Questel (usually) voiced both roles.

It doesn’t stop there. The jokes tend to be risque, and on a Freudian level the imagery is almost constantly sexual. Some of this was likely unconscious on the part of the Fleischer Brothers—Max and Dave—who were responsible for the cartoons. I suppose that it is possible—as has often been put forth—that they were unaware of the drug references in the Cab Calloway song “Minnie the Moocher,” but I’m hard-pressed to believe they were so naive that they didn’t understand Louis Armstrong singing, “You bought my wife a bottle of Coca-Cola so you could play on her vagola,” in his version of “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal, You.” How that got past even in the pre-code era still baffles me.

And there’s also a nightmarish—occasionally downright horrific—element to the cartoons. In fact, the aspect of Betty Boop, M.D. that really grasped my interest was its ending where a baby drinks a bottle of “Jippo” (some medicine show panacea Betty is peddling) and transforms into the Fredric March Mr. Hyde from Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932). Something very like the Frankenstein Monster (Bimbo even says, “It’s alive!”) pops up in Betty Boop’s Penthouse (1933). Ghosts of all kinds, ambulatory skeletons, witches, demons and monsters show up with very little provocation in places not always expected. And then there is the uncertainty of everything. These cartoons are as surreal as it gets. Anything might transform into something else without warning and supposedly solid inanimate objects often have the texture of human flesh (and the shape is often phallic). It’s all pretty disconcerting—but in a good way.

Beyond that is the animation style itself. You may think you know the Fleischer style their 1930s Popeye cartoons—the good ones with the cabin doors opening and closing for the credits—and to some degree that’s true. The drawing style is similar and the backgrounds the same cracked plaster, slightly rundown motif. Then too, a kind of rhythmic style achieved by the intelligent use of cycles (repeated actions) is there, but the Boop cartoons have a rhythm all their own. They’re more rubbery—for want of a better word—and some of them seem to almost throb. There simply isn’t anything quite like them.

The original idea did not center around Betty, but rather around Bimbo the dog. Betty was an afterthought—a kind of girlfriend for Bimbo. That’s the reason why the earlier versions of Betty give her long, floppy ears. That these dog ears are attached to an otherwise basically human figure is actually downright peculiar, but then so are most of the Bimbo cartoons that contain the dog Betty. Take Mysterious Mose (1930), which based on the novelty song by that name. There’s really little more here than a situation, which finds Betty cowering in bed, apparently from the threat of the title character. She’s so scared that her nightgown keeps flying off. Not long afterwards, Mysterious Mose—who appears to be Bimbo—shows up and all manner of hallucinatory things occur as the song is taken up by various morphing creatures and musical instuments, including a disconcerting caterpillar playing the saxophone. Finally, Bimbo/Mose explodes and proves to have been a wind-up toy.

One of the best—and weirdest—of the Bimbo-centered efforts (at least those involving Betty) is Bimbo’s Initiation (1931). Again, it’s little more than a situation. Bimbo is happily walking along a street when he falls down a manhole and slides down a long tunnel into a roomful of strange robed figures with heads that resemble bearded bowling balls topped with candles. They exhort him to join their secret society, but Bimbo is simply not interested. These fellows, however, aren’t prone to take “no” for an answer and proceed to thrust Bimbo into a nightmare world of threats and tortures that all lead to the question, “Wanna be a member?” After a variety of these scenarios (one of which was copied exactly in live action in Richard Elfman’s 1981 film Forbidden Zone), one of the robed figures reveals itself to be Betty, at which point Bimbo wants to be a member, whereupon the others disrobe and they’re all Betty. As if to celebrate, Betty and Bimbo take turns spanking each other. No comment.

As Betty became increasingly popular—and increasingly human—she took over the lead and the Fleischers resurrected their original star, Koko the Clown, to add to the mix. Perhaps they realized that there was something not quite normal about Betty having a dog—however humanoid—for a boyfriend. Taken to its logical conclusion that sort of thing just won’t play in Peoria. (Of course, today it would find a home as a website for specialized tastes. Perhaps it already has, but I don’t know and am afraid to find out—and would as soon that those with such knowledge keep their links to themselves.)

If the focus on characters shifted, the central preoccupations with surrealism and the outre did not. Betty’s adventures could take her anywhere from Betty Boop’s Bamboo Isle (1932) to Betty Boop’s Museum (1932) to Mother Goose Land (1933). In Red Hot Mamma (1934) she even went to hell, where she gave some lecherous demons the (quite literally) cold shoulder and froze Satan himself with an icy stare. Betty was unstoppable even by the big cheese of hell himself. She was not, however. immune from the Breen Office and the Production Code of 1934, and soon Betty as we knew her would be gone—replaced by an impostor in demure clothing, robbed of her garter, shorn of a number of her spit curls. She was given new sidekicks and thrust into saccharine scenarios and adventures that weren’t worth being called adventures.

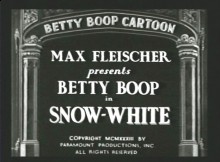

But let’s not dwell on the inglorious ending of sweet Betty. Let’s go back to those first exposures I had to her in 1973 for a bit. While Betty Boop, M.D. intrigued me and I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal You (1932) had amused me, it was Snow-White (1933) that sealed the deal. I groaned when I saw the title, thinking this was going to be a lame affair. I was perplexed when the film announced “Vocal Chorus ‘Saint James’ Infirmary Blues’ sung by Cab Calloway.” I only vaguely knew who Cab Calloway was—and that consisted of one song, “Jumpin’ Jive,” discovered on one of my parents’ Remember How Great? LPs that collected songs from Lucky Strike’s Your Hit Parade. Even with that sketchy knowledge, I couldn’t see what this could have to do with Snow-White. About six-and-a-half minutes later, I was Betty’s devoted follower and a Cab Calloway fan for life. I think my friends would say the same.

That was in my earliest days of film collecting. In fact, it was watching these films that prompted me to make the leap from Super 8mm sound (which was never satisfactory) to 16mm prints. That I had no projector seemed of small concern—as long as we had access to the Episcopal Church parish hall and their old Kodak Pageant (not to mention that Coca-Cola machine that dispensed Coke in glass bottles for one thin dime). At that time, the Betty Boop cartoons were fairly common on movie collector lists. They tended to run $16 a cartoon, which seemed pretty reasonable since features were going to ten times that amount and more. Naturally, the first Betty Boop I ordered was Snow-White.

When it arrived we made our way that night to the parish hall, taking along as many people as we could. The question in the minds of those of us who had seen the cartoon was whether it could really be as wonderful and strange as it had seemed. We needn’t have worried. No sooner had its seven minutes unspooled than someone new asked, “Can we watch that again?” We did. In fact, I’m pretty sure we watched Snow-White at least ten times that night, and we could likely have watched it ten more. It was—and to me remains—endessly fascinating on every conceivable level.

I didn’t know it at the time, but it was the second of three cartoons—the others being Minnie the Moocher (1932) and The Old Man of the Mountain (1933)—where Betty met up with Cab Calloway. And I mean that literally, since the characters to whom he gives voice are rotoscoped from his movements, so in essence—at least in terms of movement—that really is Cab up there dancing in his inimitable way on the screen. In Minnie the Moocher he appeared as the singing and dancing ghost of a walrus (who the hell thinks in these terms?). In The Old Man of the Mountain he first shows up as an owl and then as the title character. In Snow-White he first inhabits Koko the clown until the wicked step-mother (in witch form) uses her magic mirror to turn him into a ghostly creation that’s mostly legs. I doubt it many would argue that this center film isn’t the best of the three.

Snow-White is one of those rarest of rare works that just become more impressive the more you see it. In its particular case, it just become more mind-blowing the more you see it. I was discussing it with a friend the other night and we started talking about the incredible array of symbolic sexual imagery in the film. We talked about the magic mirror with its fleshy phallic handle, about Koko and Bimbo grinding their tools into powder under Betty’s spell. We discussed all the train-in-the-tunnel moments in the film and the symbolic meaning of the “Mystery Cave” in which the film climaxes amidst a riot of even more phallic imagery. Dr. Freud himself would have fainted dead away at how much of this is packed into seven minutes. And then my friend commented on the way in which Betty tugs of the appendage of the alarm clock-doorbell at the beginning of the cartoon—something I’d never noticed in 37 years and countless viewings. So I checked it out—and damned if he wasn’t right. The thing is that there is so much going on in any given shot—I’m tempted to say any given frame—that it’s virtually impossible to catch all of it. There is always more to see.

The cartoon has a bit more plot than usual, following—more or less—the Snow White story with an obvious belief that the viewer is familiar with it. When her magic mirror not only tells her that Betty is the fairest in the land, but makes a grab for this fairest of all, the wicked stepmother queen orders palace guards Koko and Bimbo to cut off the offending beauty’s head. But they are so moved by Betty’s song that they end up falling down a long shaft. which covers itself with snow to appear to be a grave. The tree she’s tied to takes pity on Betty and sets her free, but she trips over a tree stump and rolls along as a gathering snowball, which is then transformed into a kind of snow coffin that turns into an ice coffin after passing through a lake. The ice coffin slides right through the house of the seven dwarfs. who immediately beome pall bearers and ski with the coffin into the aforementioned Mystery Cave.

At this point, the stepmother discovers her orders haven’t been carried out, so she transforms herself into a witch by passing the magic mirror over her. (This is forever accompanied in my mind’s ear by the sound of a girl from 1973 crying, “Far f**king out!” at the sight.) She then glides down the open shaft and exiting steps on the heads of the unconscious Bimbo and Koko, who are awakened and freed from their suits of armour, whereupon Koko starts singing “St. James Infirmary” and joins the funeral procession in the Mystery Cave. All of this is accomplished so smoothly—aided by a marvelous soundtrack comprised of clever uses of “Please” and “Here Lies Love” from The Big Broadcast (1932)—that there’s never a reason to worry about dramatic logic.

While the other two Cab Calloway cartoons also have their key musical numbers in a cave, this one takes the prize for atmosphere, imagination and creepiness. The whole frame is alive with detail on every level—the backgrounds, which tend to illustrate such lyrics as “Then give me six crap-shootin’ pall bearers,” are particularly notable. Within the frame itself you have not only Calloway’s incomparable moves—here reduced to the barest essentials in terms of form—but various ectoplasmic manifestations move through the air in time to the song. The Calloway form is the ultimate in fleshy impermanence here, transforming into a singing $20 gold piece on a watch chain at one point, and removing its own head which turns into a whisky bottle from which it pours “another shot of that booze.”

Reading about the film doesn’t do it justice. It has to be seen to be believed and to be enjoyed. As far as I’m concerned, you can keep the Disney feature. For me, this is the real stuff. We ran this cartoon before the feature at one of the first Thursday Horror Picture Shows as part of the pre-feature entertainment. Chance are we’ll run it again at some point—maybe more. Why? Simply because it and Sweet Betty are just about the coolest things ever. I can’t think of a better reason.

T’other Ken and I agree! Great article. Love that Cab Calloway ectoplasm.

Excellent article, Ken, and a solid salute to Betty and the surreal world of the Fleischers.

I think my own introduction to Betty occurred much earlier than yours, but initially was filtered largely through what showed up on TV or the odd public domain VHS: post-code Pudgy (ugh), the occasional gem with Bimbo and Koko, and Grampy (generally considered the best of the post-code Boops, since Grampy is livelier than Pudgy and the Rube Goldberg inventiveness is at least slightly better as a proxy for the prime Betty strangeness). I was probably 16 when I discovered the pre-code goods.

I also get mild amusement out of what are essentially Betty’s cameos in the early Screen Songs which essentially star live-action personalities like Ethel Merman and Rudy Vallee (especially “Kitty from Kansas City” with the latter). But as you said, you can’t beat the pre-Hays stuff. A favorite not mentioned here is “Betty Boop for President” (1932): from the patented Fleischer transformations resulting in Betty becoming grotesque caricatures of Al Smith and Hoover to her policies when in office… and especially her opponent, the weird Mr. Nobody, easily one of the most memorable tertiatry Boop characters *not* voiced by Calloway. (“Who cares if your wife is gone? Mr. Nobody!”) And of course it all ends in an image of a large inviting glass of beer (and this was still before the end of prohibition). I showed it to a friend via an online version recently, and he was both astounded and a bit appalled (“What did Betty *do* to that poor murderer?”)

The only cartoons from the era which rival the Boops for strangeness (without the sexual vibe but arguably amping up the violence and nightmare aspects) are the utterly obscure Scrappy shorts produced by Columbia and obviously bearing Fleischer influence themselves (typical Scrappy behavior: the titular urchin yanks off the skin of a live dog to wear as a disguise; the dog runs around briefly as a blind skeleton before ramming into a wall and becoming a pair of dice).

“I suppose that it is possible—as has often been put forth—that they were unaware of the drug references in the Cab Calloway song “Minnie the Moocher””

I balk at the knee-jerk reaction some folks have when exposed to these or other odd vintage cartoons or even some live-action work (“These guys must have been on drugs!”) Both a dismissal and misunderstanding of what strangeness and creativity the human mind, or some human minds, can conceive, but also almost always provably false (though heavy boozing by vintage animators is another matter). However, that doesn’t mean the Fleischers and their animators were in anyway cloistered or unaware of what “she loved him though he was cokey” and other lyrics meant. The main animator credited on any given Fleischer short was generally the actual director, *usually* with other animators under them; Dave Fleischer (always given director’s credit) functioned more as the voice recording director, which itself cannot be dismissed, and were famously recorded *after* the animation for the most part, with obvious exceptions like the rotoscoped Calloway, leading to the famous odd under the breath mumblings of Popeye or weird asides in the Boops). Dave Fleischer functioned more closely as an essential overseer, but in what animation historian Mike Barrier has termed a “glancing, all but random way,” insisting on more gags, constant movement, and casually inserting an even more bizarre gag rather than revising or messing with individual character animation or stories (such as they were), in contrast to Disney.

I’m convinced that it was this atmosphere, the fact that the studio was New York rather than Hollywood based (which influenced the grubbier and often more ethnic/urban world of Betty compared to Mickey, rural in the earlier shorts and later clearly suburbanized), and just the fascinating time period which was the 1930s in general which led to the fever dream feel, rather than drugs.

Also the fact that on occasion (as with “Snow White,” reportedly animated/default directed by Roland “Doc” Crandall over a period of six months), one overworked animator (though likely Crandall had at least one assistant or inbetweener, this is still different compared to the closely assigned and “cast” work on the Disney “Silly Symphonies”) might essentially animate an entire short, improvising as he went, so the finished product might *indeed* be a literal fever dream.

“the Boop cartoons have a rhythm all their own. They’re more rubbery—for want of a better word—and some of them seem to almost throb. There simply isn’t anything quite like them.”

You hit the right word, actually. In animation discourse (though I’m not sure whether or not any of the actual animators at the time used the phrase; possibly), the common phrase for this style is “rubber hose animation,” and while the Fleischers weren’t the only ones to use it (the earliest examples are usually attributed to the silent era, Otto Messmer’s animation in the Felix series and Bill Nolan on the Walter Lantz Oswalds), there’s no doubt that the Fleischers basically became synonymous with it and pushed it to the extreme.

A couple of final footnotes to this very long comment: perhaps the best example of how far Betty suffered post-code (even though the series would continue for another five years) is the one color entry, “Poor Cinderella” (1934). Compared to “Snow White,” it’s a straight forward adaptation, treacly songs, “la la laing” pumpkins and lizards, the major bit of oddness being a not very funny Vallee caricature as a lonely prince, and a Betty with red hair (due to the use of the Cinecolor “two color” process,” which only allowed for the use of red and green and shades thereof, and was cheaper than technicolor). It’s also pretty darn dull and insipid (and due to the color process, even hard on the eyes).

Second footnote: You probably knew this, Ken, but for the record and another study in contrast, the designer and animator of the canine Betty in her debut short, Bimbo’s “Dizzy Dishes” (1930) and a few other early shorts (including “Bimbo’s Initiation”) was Grim Natwick. Natwick is perhaps better known for his far more prosaic work on *Disney’s* “Snow White” (animating the title character) and the Fleischer’s less interesting attempt to top with same, “Gulliver’s Travels” (animating the rotoscoped prince and princess).

Love that Cab Calloway ectoplasm.

There’s nothing quite like it. I finally saw Cab perform live in his later years. He couldn’t hit the high notes and he couldn’t do those moves, but he was still Cab Calloway.

While we’re talking about bizarre pre-code cartoons, let’s not forget Ub Iwerks’ FLIP THE FROG series over at MGM. Iwerks left Walt Disney in 1930 to set up his own studio with producer Pat Powers. The first Flip cartoon was a 1930 2 strip Technicolor affair called FIDDLESTICKS (the first color sound cartoon). A very traditional cartoon in terms of story and design.

The rest of the series was done in black and white and became increasingly strange and risque. Two cartoons from 1932 ROOM RUNNERS and THE OFFICE BOY (both on DVD in the CARTOONS THAT TIME FORGOT Series) have to be seen to be believed. In the former, Flip peers through keyholes at a woman bathing and drying off (we see her too), says “Damn” and “Hell”, and slides down a banister, crashing into a woman with a big butt and small breasts reversing them (much to her delight). Flip himself looked like a cross between Mickey Mouse and Bosko.

By 1933 Flip had worn out his welcome at MGM (Louis B. Mayer was more conservative than the Code) and Iwerks turned to making Color Fairy Tales and an outrageous liar called Willie Whopper for the remainder of the decade. He would return to Disney in 1940 and remain there for the rest of his life.

or—God forbid—only know the cartoons after the production code sanitized the cartoons into a vomitable morass of treacle that bore only a nominal relation to the original.

I had no earthly idea that anything other than the aforementioned versions of Betty Boop existed. So I would leave little hope that people my age or younger know anything different.

So, where would I be able to watch these original gems? Do copies exist on anything other than reels?

PS. On a completely unrelated note (I have been wondering this for a while and am not trying to tangent article related discussion), were you involved in/a viewer of the original Jack and the Magic Rock written by the Fran and staring a few prominent Lake Walians?

I can’t even remember how long ago I first saw a Betty Boop cartoon, but I think it was at a midnight show in the seventies when I first saw the complete Snow White, and you can probably imagine the shape I was in, but it was a phenomenal experience, and I still marvel at what a great job they did when I see it now! Pixar’s got nothing on those guys!

Handsome Hanke, I’m so glad to learn that you’re a Betty Boop fan!

Several years ago I mentioned to my mother that every “Betty” I had ever met was my own age, a WWII baby. She said that during WWII the extremely high level of patriotism was exemplified by Betty Boop and Betty Grable and that they ushered in the first wave of feminism. Those two Bettys flaunted their sexuality, independence, and intelligence—a new concept in America—and both men and women loved them.

My mother also observed that, except for a brief lapse in the 1950s when women were sent back to their kitchens in aprons and “Betty” was deemed a stodgy old name, the spirited independence of the two Bettys has stood the test of time. They are both still icons, and both men and women still love them.

Boop-oop-a-doop!

I balk at the knee-jerk reaction some folks have when exposed to these or other odd vintage cartoons or even some live-action work (“These guys must have been on drugs!”) Both a dismissal and misunderstanding of what strangeness and creativity the human mind, or some human minds, can conceive

This has long been a sore spot for me. I get so tired of being asked, “Does Ken Russell do drugs?” because he’s about the least likely filmmaker to be doing drugs I can think of. I do tend to think that everyone involved on Scared to Death (1947) was on drugs, because any other explanation is too frightening to contemplate.

“Poor Cinderella” (1934). Compared to “Snow White,” it’s a straight forward adaptation, treacly songs, “la la laing” pumpkins and lizards, the major bit of oddness being a not very funny Vallee caricature as a lonely prince, and a Betty with red hair (due to the use of the Cinecolor “two color” process,” which only allowed for the use of red and green and shades thereof, and was cheaper than technicolor). It’s also pretty darn dull and insipid (and due to the color process, even hard on the eyes).

Yes, I saw it recently because I’m working my way through that horribly laid out out 8 tape set of Betty Boop cartoons that came out in the 1990s, transferring the ones of merit to DVD-R. This would be a simple matter if they were chronological, but they aren’t. The only interesting thing about Poor Cinderella is the multi-plane camerawork. And it wasn’t interesting enough to make me keep it. Really, two-strip color doesn’t explain the red hair, though, since it could produce blacks.

Two cartoons from 1932 ROOM RUNNERS and THE OFFICE BOY (both on DVD in the CARTOONS THAT TIME FORGOT Series)

I’d love to see these. I usually eschew these cartoon sets like that because that usually amount to one or two gems and a lot of things that are tough to sit through. Has anyone done a collection of the Harman-Ising cartoons?

I had no earthly idea that anything other than the aforementioned versions of Betty Boop existed. So I would leave little hope that people my age or younger know anything different

I’m blaming your father here. As you’ve probably guessed he was one of those in attendance in 1973 both at the original screening and at the parish hall. So he certainly knows of these things. That he has kept this from you is appalling.

So, where would I be able to watch these original gems? Do copies exist on anything other than reels?

They’ve never been properly brought out on DVD, but the good ones — some of them anyway — are on various collections. I can probably help you on this. Some of them might be on YouTube for that matter, but that’s no way to watch them.

PS. On a completely unrelated note (I have been wondering this for a while and am not trying to tangent article related discussion), were you involved in/a viewer of the original Jack and the Magic Rock written by the Fran and staring a few prominent Lake Walians?

I have seen it, which is involvement enough, I think. At the time it was made, I think I was busy covering a G.I. Joe in tin foil and stop-animating him as a giant robot. Whether or not that’s more sophisticated is a personal call.

I think it was at a midnight show in the seventies when I first saw the complete Snow White, and you can probably imagine the shape I was in, but it was a phenomenal experience

I tend to suspect that the young lady with the “Far f**king out” outburst was in a similar condition.

Handsome Hanke, I’m so glad to learn that you’re a Betty Boop fan!

I find it hard to imagine anyone who has seen prime Betty who isn’t a fan.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I’ve never seen a Betty Boop cartoon beyond the occasional short glimpse used in other films or commercials. I’m aware of the difference between pre-code and code films but never tied it to cartoons. Since you’re recommendations have been all good for me so far in the few months I’ve been lurking here I’ll get some on my netflix cue.

Oh yeah, and thanks for the ‘Gorgon’ rec. I’d forgotten how good those Hammers could be. Seeing Lee in an unusual characterization was a treat. No sequel setup. No Hollywood closure. No winking. No pretentious self-awareness. No reliance on special effects over plot. Just horror with a horror ending. About the level of Greek tragedy realized in the Wolfman. Neat.

Since you’re recommendations have been all good for me so far in the few months I’ve been lurking here I’ll get some on my netflix cue

Be wary here. There are some awful collections out there and all of them have some awful post-code rubbish in them. Try to find something that has Sbow-White (most definitely), Minnie the Moocher, The Old Man of the Mountain, I Heard, Bimbo’s Initiation (unlikely in these sets) and I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal You.

Just horror with a horror ending

An altogether unappreciated quality — and one of the reasons I want to include Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon (aka: Curse of the Demon) in the August horror movie line-up.

I’m blaming your father here. As you’ve probably guessed he was one of those in attendance in 1973 both at the original screening and at the parish hall. So he certainly knows of these things. That he has kept this from you is appalling.

He’s in for a stern talking to.

They’ve never been properly brought out on DVD, but the good ones—some of them anyway—are on various collections. I can probably help you on this. Some of them might be on YouTube for that matter, but that’s no way to watch them.

Hit me up on facebook with any help you can offer. But keep in mind I don’t have a laserdisk player, haha.

I have seen it, which is involvement enough, I think. At the time it was made, I think I was busy covering a G.I. Joe in tin foil and stop-animating him as a giant robot. Whether or not that’s more sophisticated is a personal call.

My filmmaking career started out in similar fashion to yours.

He’s in for a stern talking to.

And well he should be. I’m actually surprised this discourse hasn’t prompted him to show up — unless he realizes that his position here is indefensible.

My filmmaking career started out in similar fashion to yours

In which case, we will call it more sophisticated.

And well he should be. I’m actually surprised this discourse hasn’t prompted him to show up—unless he realizes that his position here is indefensible.

Okay, I doubt this is of general interest, but there seems to be a dynamic where S of R seems to appreciate stuff more when he discovers it himself or hears about is from someone like an actual, professional film critic whose opinion he respects, than when I suggest it. That is not to say that he never values my opinion on film, music, art, ect. (I like to take at least some credit for his considerable knowledge of and appreciation for 70’s music for example). Anyway, I’m glad he read the column, and is seeking out the Betty Boop cartoons. Apart from this, I can only beg forgiveness.

Now I really feel nostalgic for SNOW WHITE myself!

Okay, I doubt this is of general interest, but there seems to be a dynamic where S of R seems to appreciate stuff more when he discovers it himself or hears about is from someone like an actual, professional film critic whose opinion he respects, than when I suggest it.

Okay, that actually sounds plausible — certainly it’s within the realm of human nature.

Now I really feel nostalgic for SNOW WHITE myself!

I’m kinda nostalgic to have Greg accompany the soundtrack on a tuba.

Thanks for the heads up. Always associated Betty Boop with a consumerist fad but dled the cartoons and was really amazed.

Always associated Betty Boop with a consumerist fad

I think it became one.