The Asheville Film Society starts its month-long tribute to British filmmaker Ken Russell (1927-2011) with a double bill of two of his best and most popular BBC films — Isadora Duncan, the Biggest Dancer in the World (1966) and Song of Summer: Frederick Delius (1968). The first is about American dancer Isadora Duncan (Vivian Pickles), while the second covers the final years of British composer Frederick Delius (Max Adrian). Though they are both clearly the work of the same artistic sensibility, the two offer a marked contrast in tone. Isadora (which is probably my favorite of Russell’s BBC films) is bold and exuberant — literally bursting onto the screen in a torrent of images presenting an encapsulated version of the dancer’s eccentric life after the fashion of a newsreel running at breakneck speed. Song of Summer is a much quieter work. It’s more of a chamber piece that is sometimes reminiscent of one of Ingmar Bergman’s more intimate dramas, though in markedly Russellian terms. The two tones were adopted because they suit their respective subjects, but they also serve to illustrate what might be called the two sides of Ken Russell — two sides that, I must say, often cross over into the other. Many of Russell’s critics tend to present him as invariably over-the-top and flamboyant, thereby selling short the fact that he is also capable of quiet reflection — even introspection — and creating moments of subtle beauty and humanity.

When Ken Russell started making films — short films — for the BBC in 1959, the idea was that he was to make documentaries. These were also meant to be straightforward documentaries, but they almost immediately developed a personality of their own in the way that Russell cut the films and the way he matched music and imagery. (His use of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Sinfonia Antarctica is his 1961 short on Antonio Gaudi provides an interesting early example.) But the approach was too constraining for Russell, who more and more wanted to dramatize his subjects — an idea the BBC was resistant to out of the belief that the public would believe any such dramatization would be mistaken for actual documentary footage. All the same, by 1961 he had managed to work some of his ideas into a film on Sergei Prokofiev — including a brief glimpse of an actor playing Prokofiev reflected in a pond.

The following year in his landmark film Elgar, he was allowed to craft scenes and use actors — but they couldn’t be seen in close-up and they couldn’t speak. Since the film proved immensely popular, he was given a little more freedom, which he kept expaning upon. In The Debussy Film (1965), he hit upon the ingenious idea of making something very like a full-scale biographical film on Claude Debussy by turning it into a film about the making of a film on Debussy. Since this worked and angry crowds didn’t storm the BBC with torches ablaze, his Isadora needed no such distancing. Instead — though held together somewhat by a narration — it was allowed to be a biographical film in its own right.

For the uninitiated, Isadora is a terrific starting point. It has nearly all the elements associated with a Ken Russell film, even if sometimes in incipient form. As noted, it’s a film that just bursts onto the screen — something that is a staple Russell item. It’s also something of a utilitarian trick designed to catch the TV viewer’s attention before the channel got changed. In this case, it’s a crowd yelling out each letter of the name Isadora as illmunated letters appear on the screen, followed by the guaranteed show-stopper of a stark naked Isadora (pretty clearly not Vivian Pickles) cavorting on a stage until she’s discreetly covered and carried off by a policeman. If that wouldn’t keep them watching, nothing was likely to.

This turns out — in something of an homage to Citizen Kane — to be a breathless newsreel version of the dancer’s life and death done in the most lurid, tabloidesque manner imaginable. (Trivia buffs note that the jazz band seen on the top of a hearse at one point supposedly contains members of the Bonzo Dog Band, and Russell himself — who shows up again in the film as Isadora’s driver in Russia — appears as the one-legged man who thwarts Isadora’s attempt to kill herself by walking into the sea.) Apart from being wildly entertaining, the opening does two very important things. The newsreel presents the better-known public version of Isadora Duncan, while the body of the film will present a more complex portrait. It also offers our first glimmer of Russell presenting period figures as the pop stars of their day. Isadora and her husband Sergeir Yessenin (Alexei Jawdokimov) are seen acting like badly-behaved rock ‘n’ roll royalty, trashing a hotel room and pushing a grand piano out the window of the seventh floor room. Russell will reinforce this by shooting her stage appearances much in the manner that Richard Lester photographed the Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night (1964). Consciously or not, Russell was making his period heroine resonate with younger viewers — something that would find full voice with a vengeance nine years later in Lisztomania.

At this point, the film becomes a little more sober-minded as it actually settles in to tell Isadora’s story in earnest — with the aid of the writer Sewell Stokes, without whom the project may well have been impossible. When Russell first embarked on the project, he found that virtually all the rights to books about Isadora had been bought up by the Hakim Brothers for their feature production Isadora (1967), which Karel Reisz was preparing to make with Vanessa Redgrave. They’d bought Stokes’ book on her last days, too, but that didn’t prevent Stokes himself from co-writing Russell’s film, as well as briefly appearing in it and providing a slightly superfluous narration. With Stokes onboard, newspaper accounts and a certain amount of invention (which seems only reasonable, since Duncan’s own autobiography was almost entirely fiction) Russell was able to create his portrait of Isadora.

Casting Vivian Pickles (best known for playing Harold’s mother in Harold and Maude five years later) was a masterstroke. She not only looks more like Isadora Duncan than Vanessa Redrgrave ever could (Isadora was anything but reed thin), she beautifully captures the over-the-top unconscious vulgarity of the woman and she makes her essentially and innately American. She’s glamourous yet tacky, beautiful yet only slightly, and, like the film itself, she exudes a sense of life — outrageously and fully-lived. She seems too preposterous to be real, yet her reality is never in question.

By virtue of its length (the film is only slightly over an hour), the details are often sketched in — in a lovingly humorous manner — yet the film never feels in the least bit rushed, perhaps because we’ve already been presented with that newsreel version of her life. Her relationship with millionaire Paris Singer (Peter Bowles) is cleverly conveyed in a series of scenes detailing the inevitable disintegration of any such relationship for the self-absorbed — and somewhat man-crazy — Isadora. Stokes occasionally tosses in a pithy observation that helps keep her own absurdity in place, as when he describes her relationship to the Russian poet Yessenin — “He was also an epileptic, a lecher, a drunkard, a layabout, and a thief — Isadora found him irresistible.”

Much of the material also affords Russell the ability to simply indulge in his love of filmmaking for its own sake. For instrance, he gets to stage a knockabout silent film style comedy in his depiction of one Yessenin’s combined bouts of lechery, thievery, and ill-timed outbursts of communist propaganda. It might almost be out of a Keystone Kops movie, yet it’s brilliantly intercut with Isadora dancing to Tchaikovsky’s “Marche Slave” onstage. The music is used to match the action in both scenes, yet there’s never anything remotely comedic about Isadora’s symbolic dance of the Russian people overthrowing their Tsarist oppressors. The amazing thing is that these two elements are perfectly combined, yet totally separate in tone — and yet they will dovetail into one disaster as far as America is concerned.

Actually, all of the dance sequences are remarkably serious in intent and execution. They range in tone from the celebratory to the hopeful to the vainly hopeful to the outright tragic in the final public performance we see. That last dance — set to Wagner’s “Liebestod” — finds the aging, alcohol-addled Isadora trying to blot out the tragedies and disappointments of her life, only (through intercutting) to be confronted with her memories everywhere she turns. Indeed, the whole arc of the film is traced through these dances, which take us all the way to Isadora’s freakish death — an event as improbable as anything about her life, and one that Russell foreshadows in the way in which her dances invariably end.

But Russell loves his Isadora and he’s not content to go out without giving her the send-off he feels she deserves. He makes right something that was never made right in Isadora’s own life. It’s been done since — Tim Burton’s Ed Wood (1994) comes to mind — but it’s never been done any better or any more movingly or joyously as it is in this film. That reality comes back at the very end to slap the viewer in the face does nothing to lessen its impact. The heartbreak isn’t so much in the reality, but in the film’s celebration of what might and should have been. Only in art are we given the ability to go back and be kinder than reality was. A romantic notion? Very possibly, but what a perfect gesture for a character like Isadora Duncan.

Song of Summer is a different proposition, but one born of the same worldview. For years, Russell cited this as his favorite of his films. That’s understandable — and I wouldn’t say it was wrong (to the degree that a favorite can even be wrong) — but I would caution against taking his word on any given film as etched in stone, because it was known to shift a lot over the years. Still, it’s a great film and particularly notable as the first of his TV biographies not to rely very much on a narration. It is mostly a film that tells its own story. I likened it to Bergman at the beginning of this piece, and I think it’s a good analogy, but don’t take it too far, because it’s every inch a Ken Russell film.

You may note that the film is devoid of a “grabber” scene at the opening. That wasn’t originally true. As broadcast the film opened with Laurel and Hardy dancing in a clip from Way Out West (1937), which was being accompanied on a cinema organ by Eric Fenby (Christopher Gable). The footage of Fenby at the organ remains in the current prints, but because it never occurred to anybody to bother about ancillary rights when Song of Summer was made, the BBC doesn’t own the rights to the Laurel and Hardy footage. (Similarly, a brief sequence from Leni Riefenstahl’s 1938 Olympia was excised from Isadora, except for a single shot left in the “Liebestod” scene.)

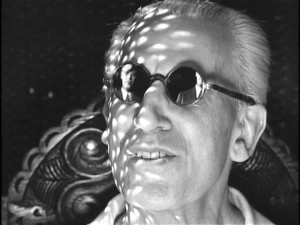

The film details the final years of Frederick Delius. At the time the film opens, Fenby encounters a piece of music by Delius on the radio and it speaks to him as no music ever has. Learning that Delius is now blind and completely paralyzed, he writes to the composer, offering his services in any capacity. Delius’ wife, Jelka (Maureen Pryor), writes back, inviting Fenby to come stay with them in France where he might possibly be able to get some last compositions in Delius’ brain down on paper. What Fenby hadn’t reckoned on is that this will take years — and that the composer of this beautiful music that so enraptured him would turn out to be a self-absorbed, irritable, demanding, and frequently just plain unpleasant old man.

The bulk of the film follows the relationship of the two men — and that of Jelka — which is anything but smooth, as becomes evident when Delius tries to dictate music by uttering a series of very unmusical noises (“Terr terr terr—terr terr terr”) rather than call out the notes. In their first sitting, Delius manages to reduce Fenby to tears and send him running from the room, which in turn prompts Delius to tell Jelka, “That boy is no good.” Cooler heads — and the even-tempered, long-suffering Jelka prevail — and an uneasy alliance that turns into a deep, if very odd, friendship comes into being.

In one sense, that’s really all there is to the film, but that hardly explains the warmth, the sense of generosity, and the overall quality of the film. Some of it is due to the performances. Max Adrian is here — in his first of four indelible performances for Russell — simply incredible. He manages the unthinkable task of making the essentially unlovable lovable. There is nothing about Delius that is easy. He’s always demanding, always thinking of himself. And he’s demanding in ways that have nothing to do with his music, as in his constant attacks on Fenby’s recent conversion to Catholicism, exhorting the pious young man to “throw away those great Christian blinkers,” and arguing, “English music will never be any good till they get rid of Jesus,” (Years later, Ken Russell quipped to me, “Well, they got rid of Jesus and it still isn’t any good”—not that I think he really believed that, but he couldn’t resist the comeback, especially after being subjected to my Max Adrian impression with the line.)

But Adrian isn’t acting in a vacuum. Christopher Gable — in his first of six Russell films — more than holds his own as the sensitive Fenby, while Maureen Pryor — in her first of two Russell appearances — makes Jelka both strong and heartbreaking. And then there’s the quiet intensity with which Russell handles the material — not to mention the frequently astonishing scenes where he matches music and image in that way that no one else ever did.

What is perhaps most interesting about the film thematically lies in its portrait — a common one for Russell — of presenting just how far short of a man’s work the man himself is likely to fall. This is often mistaken for anger on his part by detractors, for a sense that Russell himself feels betrayed by his own heroes. This, I think, is entirely off-base. On the contrary, what he presents is admiration for what wonders and beauty these tragically flawed human beings were able to create. As the years go by — if you follow the progression of Russell’s filmography — you can detect a growing sense that he comes to suspect that these flaws were part of what allowed them to create their works, not something that held them back. The truth lies more in their creations than in their lives.

There’s something else afoot here — a theme that Russell returns to time and again. Here’s the classic case of one talent — Fenby’s — devoting itself, even obliterating itself in the service of another, probably greater talent. This kind of sacrifice is central to Russell’s work and his essentially Catholic (even if lapsed) worldview. But I can’t help but wonder if it isn’t more personal than that, since so much of Russell’s work is centered on the celebration of other people’s talents. Isn’t Russell himself a kind of Eric Fenby, devoting his life to shining a light on the works of others? The question is whether he ever completely realized that in so doing, he was creating masterworks of his own.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.