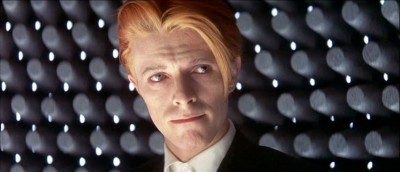

For the 35th anniversary of Nicolas Roeg’s 1976 sci-fi classic (we’re talking intelligent sci-fi, not space-opera stuff), The Man Who Fell to Earth, starring David Bowie as a mysterious visitor from another planet, Rialto Pictures has brought out brand new, remastered 35mm prints of the complete version of the film for screenings in select theaters. This week the film makes it to The Carolina in Asheville for one show on Wed., Nov. 9 at 7:30 p.m.

It’s very strange to realize that Nicolas Roeg is not better known today than he is. In the 1970s — right up through his 1980 film Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession — a new Roeg film was something of an event, highly publicized not just in film magazines, but in mainstream publications as well. (The Man Who Fell to Earth was given strong coverage in Playboy, for example.) The situation is stranger still when you realize that a panel of British film-industry people — including directors Sam Mendes and Mike Leigh — recently voted Roeg’s 1973 thriller Don’t Look Now the best British film of all time (and his 1970 film Performance came in seventh). I don’t happen to agree with the choice — even among Roeg’s films, I don’t think Don’t Look Now is his best (I think The Man Who Fell to Earth is better, for one) — but the point is he simply ought to be better known by people interested in film than he is these days.

Slowly — and I would say, elegantly — paced, The Man Who Fell to Earth is one of the odder films ever to play mainstream cinemas — though it suffered 20 minutes of cuts in order to do so in 1976, and there were some pretty odd movies playing in multiplexes in those days. It can be maddening and it can be confusing, especially if you don’t just “go with it” and allow it to reveal its secrets at its own pace. I remember being a little perplexed in 1976, but seeing it years later with the missing footage restored, it made perfect sense. Of course, something else had changed in the meantime: Roeg’s tendency to ignore a traditional linear narrative no longer seemed as startling as it once did.

Densely layered and working under the assumption that the audience has both a reasonable attention span and a degree of intelligence, the film doesn’t even lay out its plot until 90 of its 139 minutes have passed. Even when it does, more or less, explain itself, it keeps many of its mysteries to itself — and leaves them up to the individual interpretations of its viewers.

Bowie plays Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien from a never-identified planet who pretty much literally falls to Earth (at least from what we see). He arrives with nine basic patents, which quickly transform him into a very wealthy individual. (Note the word “individual,” because that’s key to understanding the film’s perspective on big business.) The story then simply follows Newton’s fate on Earth. It suggests much and tells little. I intend to tell very little of the plot either, because viewers should discover on their own what drives — and distracts — Newton.

The film can be read as a kind of picture of Bowie himself — touching on his androgyny and bisexuality (in one reference), and even offering a fantasticated concept of his emergence as a rock star. (Being made in 1976, the picture doesn’t quite get the full force of his chameleon qualities.) The film would in fact be unthinkable without Bowie. So much of the effect Roeg achieves with Newton’s other-worldliness is deeply grounded in this quality being part of Bowie’s own persona. (In much the same way, Roeg had used Mick Jagger’s persona in Performance.) Everything about Bowie — especially at the time the film was made — was so foreign that he might have been from another planet. The fact that neither Roeg nor Bowie were Americans probably added another level of disorientation to the film.

Watching the film again, I was surprised to realize that this 35-year-old film has turned out to be prophetic, and, in so doing, demonstrates one of the wonders of great films: their ability to mean different things at different times. I’m not sure there is any more pertinent image for our time than the one of the increasingly media-addicted Newton writhing in his chair screaming, “Get out of my head!” at a wall full of jabbering TVs he’s gathered around him. The point is he could turn them off — the controls are right there — but he doesn’t. That ought to hit home with just about everybody I know — myself included.

It’s a beautiful film — there’s scarcely an uninteresting composition in the entire movie — and a disquieting, thought-provoking one, especially as concerns the idea that humankind would not be satisfied until it turned Newton into one of us (despite the fact that he’d already managed to adopt most of our worst traits). Roeg’s film leaves you with much to think about in ways few movies do.

And that touches upon my reaction to seeing this film upon its release in 1976, along with some friends. Aside from its glacially-slow pacing

I think it was Andrew Sarris who said that there’s only one way to make a slow film slower and that’s to cut it where it loses the intended rhythm and becomes confusing in the bargain.

“It can be maddening and it can be confusing, especially if you donТt just Уgo with itФ and allow it to reveal its secrets at its own pace. I remember being a little perplexed in 1976, but seeing it years later with the missing footage restored, it made perfect sense.”

And that touches upon my reaction to seeing this film upon its release in 1976, along with some friends. Aside from its glacially-slow pacing (“elegantly” to some, I guess), I can’t recall much about it at all, save for the fact that it was hard to follow and bored me to tears. I was not aware of the missing footage, but based upon this review, I probably owe it to myself to watch it again in this restored version.

The situation is stranger still when you realize that a panel of British film-industry people

I can see it more with Nolan than the other two.

While browsing the Sci-Fi/Fantasy titles on Netflix Instant, I discovered a 1987 TV remake starring Bruce McGill and Beverly D’Angelo. What can you tell me about this bizarreness?

First I’ve heard of it.

“It’s a beautiful film — there’s scarcely an uninteresting composition in the entire movie — and a disquieting, thought-provoking one, especially as concerns the idea that humankind would not be satisfied until it turned Newton into one of us (despite the fact that he’d already managed to adopt most of our worst traits). Roeg’s film leaves you with much to think about in ways few movies do.”

Such a tribute to the film, Roeg, and Bowie.

I imagine when you have an opening in your film society schedule, that this will be shown. Seeing it on the big screen in the aftermath of such a loss would be a gift.

I will try to fly over if you do find time to show it.