- Alyson Johnson-Sawyer, executive director of adult day services at CarePartners , describes the adult day care program as “ivery loving and safe and welcoming.” Alicia Funderburk.com

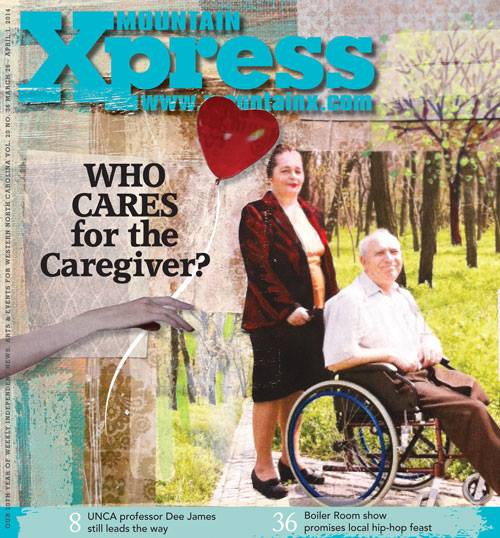

- Cannan Hyde and her husband James have been active in community outreach and education since James’ cognitive impairment diagnosis in 2010. Alicia Funderburk.com

- Karen Austin started helping her father around the house in 2010. “That morphed into a situation where I’ve been living with him and taking care of him 24/7 for the past two years,” she says. Alicia Funderburk.com

- Mary Donnelly began the MemoryCaregiver Support Network at MemortCare after her own experience caring for her mother with memory loss. Alicia Funderburk.com

Photos by Alicia Funderburk

Karen Austin still had her own children to look after when she began caring for her mother, who’d been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. That was seven years ago. Soon after her mother passed away, her father began showing signs of memory loss. By 2010, it was clear that he, too, needed full-time care. “I was coming over in the morning and staying with him until I tucked him in at night,” says Austin, “and that morphed into a situation where I’ve been living with him and taking care of him 24/7 for the past two years.”

By that time, Austin’s youngest child had graduated from high school, and she felt she could take on the role of full-time caregiver. “I went from working full time to working part time to not having a job at all, because I couldn’t manage even a part-time job taking care of my parents,” she explains. “So my lifestyle went from going to work and being out in the world to slowly sort of collapsing in on itself. … Dad now is in what they call the moderate to severe stages of Alzheimer’s. So you can’t really have a conversation. Interpersonal actions are really limited. So you need to get some sort of contact with the outside world or you will go constantly crazy. And that’s where the support groups came in.”

People diagnosed with an incurable or terminal debilitating illness face challenges almost inconceivable to those who are healthy. But the impact on the loved ones who care for those patients, while fundamentally different, can be equally profound.

Like Austin, Karyn Robinson attends a support group through MemoryCare. Her husband was diagnosed with early onset dementia nearly 10 years ago; for the past five years, he’s been living in a facility. But while Robinson’s caregiver role has shifted, it hasn’t ended.

“As he progresses, I have to progress,” she explains. “As he changes, I have to figure out how to move along with those changes. When he first went in, we could have a conversation, and he could tell me what he needed. At this point, he can’t tell me what he needs.”

For both partners, that kind of identity loss must be heartbreaking. Robinson knew her husband had to leave the house when his disease progressed to the point that he threatened her life. She says her support group was instrumental in making her understand the severity of the situation, and MemoryCare staff helped her place him in a suitable facility. The Asheville-based nonprofit provides assessment, treatment and support services for people with cognitive impairment and their families.

Cannan Hyde lives in Black Mountain with her husband, James, who was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment in 2010 and is now in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Cannan is a retired clinical social worker; James is a retired professor of psychiatry. Since his diagnosis, the couple have been active in raising awareness about the disease and encouraging people to seek out resources and support.

Cannan says she’s learned two things that are really important. “One is that I want to help people get over the stigma of this diagnosis. … People are hesitant to talk about it and to let people know, so I think that can go a long way toward helping caregivers. And the second thing is, we want people to know how much help is out there.”

Many local resources

Although their individual circumstances vary, these three women have much in common. They all care for loved ones with memory loss; they all attend support groups through the MemoryCaregivers Network, an auxiliary resource for caregivers whose loved ones have dementia. And all three are exceptionally eager to educate themselves and others about long-term caregiving — whether it’s for someone with dementia or any other ailment.

Mary Donnelly, the network’s director, knows how hard it can be to access the support and resources that caregivers of whatever sort need in order to remain healthy and connected to their communities. Her experience caring for her mother is what prompted her to start leading three dementia-related support groups for MemoryCare.

Donnelly says her experience was characterized by “massive amounts of not understanding what was going on” when her once-capable, independent mother began confusing night with day and could no longer manage her finances. “We were beginning to see signs that she wasn’t eating properly, or cooking properly, or storing food properly. There was a lot more going on than we realized at the time, because you don’t know what to look for if you don’t know what to look for.”

Looking back on it, says Donnelly, “You realize, ‘Gee, I wonder why I didn’t see that,’ but you don’t. Caregivers don’t see the forest for the trees: They’re just right in the middle of it.”

Despite these daunting challenges, Western North Carolina is rich in resources for caregivers. Besides support groups, the MemoryCaregivers Network’s Caregiver College program helps caregivers understand their loved ones’ illnesses. CarePartners offers support groups, adult day care and education for caregivers of all kinds, not just those dealing with cognitive impairment. Elder Club, a program of Jewish Family Services of WNC, also provides respite and case management for a range of caregivers. And two other local nonprofits, the Land of Sky Regional Council and the Council on Aging of Buncombe County, help steer caregivers to the appropriate resources, including workshops, home care providers and support groups. In some cases, Land of Sky can help families cover the costs of caregiving, though that funding has decreased in recent years and there’s a waiting list.

Yet for people struggling to manage both their own life and the life of the person they’re caring for, merely finding time and energy to research the available resources and access that support may feel overwhelming.

Diagnosis

Confronted with a loved one’s chronic illness, caregivers often neglect their own health — a mistake as common as it is damaging, says Dr. Amy Cohen, medical director of CarePartners’ PACE program.

“It goes underrecognized that caregiver health can be quite poor,” she notes. “They often have more chronic diseases themselves, and it’s like a circular argument: chicken or the egg? Is it because they’re taking care of this person and neglecting their own needs and preventive measures? Or is it that they have this increased stress?”

Caregivers, notes Cohen, typically don’t feel their own health is as important as that of the person they’re caring for. “Another thing is that a lot of these people perceive that they don’t have enough time for exercise or to maintain a healthy diet,” she adds. “They just do what’s quick, which is to eat snack crackers or McDonald’s drive-thru, and therefore, they are more at risk for these diseases.”

For caregivers who are already spread so thin, even simple things like having lunch with a friend, taking a walk in the woods or enjoying some time alone can be hard to arrange. Yet experienced caregivers and health professionals alike stress the importance of taking time for self-care.

“It’s amazing,” says Austin. “I’ve seen it in people in our support groups who have finally gotten to the point where they put their loved one into a facility, or their loved one has passed away, and the next month they invariably look 10 years younger. You just don’t realize how much it’s wearing you down. So even if you don’t think you need it, take care of yourself,” she advises.

Barriers to seeking help

Of course, for caregivers juggling jobs, financial burdens, family dramas and the unceasing demands of their role, finding time for proper self-care may be easier said than done.

Programs such as adult day and home care can help free up time, but Carol McLimans, family care specialist at Land of Sky, says that in the four counties she serves (Buncombe, Henderson, Madison and Transylvania), there’s a waiting list for respite care. And while the demand for caregiver resources has increased considerably since the federal National Family Caregiver Support Program was established in 2001, “the funding has gone in the opposite direction.” Still, McLimans says most of her clients qualify for a $1,000 stipend for respite care.

“A big thing,” she notes, “is that caregivers don’t self-identify as caregivers: They’re just husbands, wives, sons, daughters.” Nancy Hogan, family consultant for Project C.A.R.E., which partners with Land of Sky, remembers meeting a man whose wife had Parkinson’s. “I kept referring to him as the caregiver,” Hogan recalls. “And he said, ‘Is that what I am now?’ It was really kind of pointed. It was a real transition in his thinking.”

Shame, guilt and denial can also keep caregivers from seeking assistance, says Cannan. “People need to realize that hiding this, or keeping it a secret, or not asking for help doesn’t make sense, now that there is so much available,” she points out. “Part of it is that they’re embarrassed or ashamed or think it’s a sign of weakness, but if they can work through that, what they find is not only is it helpful for them, but then they can be more helpful to other people.”

Respite

Adult day care programs serve a wide range of participants, providing much-needed social stimulation. Most local programs charge a flat rate per day, and some have medical staff on hand.

“It provides a social setting that’s safe and is pretty unique,” says Alyson Johnson-Sawyer, executive director of adult day services at CarePartners. “Participants who have moderate to more severe impairments,” she notes, “aren’t going to fit in with other types of social situations very well. For instance, they might be embarrassed if they have difficulty finding the right words and that kind of thing. But in this setting, it’s very loving and safe and welcoming, and it’s really neat to see people establish friendships and sometimes even romantic relationships.”

In addition to activities such as Oscar-viewing parties and crafts, CarePartners’ adult day care program includes medical staff who can administer medications, monitor blood sugar and perform other basic functions. Socializing has huge health benefits for the participants, and meanwhile, says Johnson-Sawyer, caregivers get a break.

Jewish Family Services’ Elder Club welcomes participants of all faiths. Executive Director Alison Gilreath says caregivers often tell her they “used to play bridge” or “used to garden” but have lost touch with those hobbies. “It’s important to find something they can do for themselves, even if it’s just a few hours a week,” she stresses.

Of course, caregivers don’t necessarily use that extra time to relax. “Ideally, they use it to refresh themselves, so they can go back and do their job effectively,” notes Hogan of Project C.A.R.E. Unfortunately, however, “If you’re just not used to having a lot of free time, you feel pressure to get a lot accomplished and don’t even know how to make use of it. Some people run around and come back exhausted, because all they’ve done is run errands.”

Cannan, meanwhile, encourages caregivers to consider other ways to lighten their load. “They’re going to need all the strength that they can possibly have, for maybe years: We’re not talking days with many of the chronic illness that are out there,” she points out. “If you don’t start early on getting help and taking care of yourself, then you’re going to get too worn out as this progresses down the road.”

Cannan, for instance, recently hired someone to clean her house twice a month. “That’s $100 a month in our budget,” she says, “and that’s not necessarily easy, but it’s just made a huge difference knowing that every other week my floors are going to get mopped and my house is going to get cleaned really well. That seems like a small thing, but that’s the kind of thing you have to start doing early on, or else it just starts accumulating and accumulating, and you’re too worn out to even function during the day.”

Sympathetic listeners

Over time, notes Donnelly, most caregivers will have to deal with feeling misunderstood and isolated.

Austin, who’s been attending one of Donnelly’s support groups for three years, agrees. “If folks are not in that situation, it’s really hard for them to understand. They just don’t quite get it. Matter of fact, at one of the support groups, we were teasing about making T-shirts that said, ‘You just don’t get it: It’s a caregiver thing,’” she adds, laughing.

Austin began attending a support group when she realized she wasn’t getting out as much as she used to. She’d stopped working outside the home, and the demands of caregiving were changing, making it harder for her to manage her daily tasks. “It goes from fixing the meals to feeding the food, from cooking regular meals to fixing puréed food and managing more and more medicines, you know. It just gets more intense.” Besides providing a nonjudgmental listening ear, many group members had been in that situation before and could offer advice.

Family members, notes Cannan, can be extremely supportive and helpful — or not. Her own daughter and son-in-law, she says, have been downplaying the severity of James’ condition, unable to accept his diagnosis.

Donnelly says this is common among the families of people in her groups, and it can be extremely frustrating for the primary caregiver. “Frequently you will have visiting family members and friends that come in, haven’t seen the loved one in months, and they will say, ‘He looks great! I think he’s doing great!’ And they go back home and the caregiver’s saying, ‘Well, gosh, maybe I’m wrong. Maybe he’s getting better.’” But as Donnelly points out, people with dementia and similar chronic illnesses don’t get better. “That’s one of the toughest things that caregivers go through; we hear that one all the time,” she reports.

Cannan has formed lasting friendships with three of the wives in her support group. “We go out for lunch, and we laugh and we cry and we’re able to share stories,” she reveals. “We can all sit there and cry, and five minutes later we are cracking up laughing because of something really funny one of our husbands did. And it’s just so wonderful: We spend three or four hours together once a month, and it just helps our spirits so much. That’s the kind of thing we’ll keep doing on through our husband’s illnesses, and it will help keep us going.”

Prescription

Despite all the help these organizations can offer, some caregivers may still be left feeling underserved, isolated and overwhelmed, says Donnelly, stressing the importance of the informal resources that often go untapped. “That would be friends, families, neighbors, book club members, church members,” she explains. “If you know someone who’s caring for a spouse or a parent who has memory loss, stay in touch with them regularly; call them regularly. They are going to have inertia, they are going to be isolated, they’re not going to know to ask for help.

“Don’t believe a caregiver when they say, ‘Oh, we’re fine, thanks,’” she continues. “They are not. They may be doing pretty well now, but heads up: If they start pulling away, if they aren’t coming to church anymore, if they drop out of book club, if they aren’t available to go out to dinner anymore, then stay in touch with them in other ways.”

Austin agrees. Reflecting on nearly a decade of experience, she says caregiving is “trying and difficult and stressful … and it is also at times incredibly rewarding.” In addition, she notes, “I was a rowdy teenager, and I owe my parents this.”

“Something that everyone in the support groups kind of nods their heads with,” continues Austin, “is when people on the outside of the situation come up and say, ‘Oh, you’re just a saint.’ I’m not doing this to be a saint, and I’m not real comfortable with that.

“If you want to make me feel good, instead of telling me how saintly I am, or how inspired you are by how hard I work, come over and spend a couple hours visiting with me, so I can have human contact. Come over and sit with dad so I can go see a movie. I would like to go see a Tourists game. I love the Tourists, and I haven’t been to a game in four years.”

— Lea McLellan can be reached at 251-1333, ext. 127, or at lmcclellan@mountainx.com.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.