If you wander off the beaten path in Mars Hill, you might come to a dead end on Mount Olive Drive in the community of Long Ridge, not far from the town’s university. There sits a solitary building that appears forlorn and somber, at first.

A peek inside reveals fragments of green tile still clinging to the floor and chalk graffiti decorating the walls. There’s a chimney, sturdy as ever, and evidence of pipes that likely ran to coal stoves. A pale line runs up the length of the chimney, as if a wall once stood there and neatly bifurcated what’s now just one big room.

The building seems inauspicious, until you peer into its legacy: In fact, this humble structure is a rare standing relic of the Jim Crow South and a monument to how Madison County’s small but vibrant black community carved out its own education for generations. And now, the former school, which has gone by a few names over the years, is finally on the verge of getting its proper recognition, a once-fading legacy now coming back into focus.

A boon and a challenge

It’s a history that dates back to the Civil War era. After their emancipation, many former slaves stayed around Mars Hill and built new lives. “There were other areas settled by African-Americans in Madison County,” says Les Reker, director of Mars Hill University’s Rural Heritage Museum, which is helping drive new interest in the school. “But Long Ridge was the area predominately settled by African-American families.”

Black migrants from less peaceful locales swelled the numbers. “Madison and Yancey used to be one county,” Reker recounts. “Their split may have actually been because Madison was more pro-Union, and Yancey more Confederate. Many African-Americans moved to Madison from Yancey County because the Ku Klux Klan was so active in Yancey.”

A few small, spread-out schools sprang up to serve black children, and in 1905 many of these coalesced into a centralized one called Long Ridge School by the students (and Mars Hill Colored School by white school boards). This facility did the job until 1930, when it was replaced by the Long Ridge Rosenwald School, the product of a pre-desegregation push to radically improve academic options in places like Mars Hill.

Funds to build the school came from a grant of $750 (about $8,000 in today’s dollars), matched by the community and school district. The grant came from the Rosenwald Fund, which was the brainchild of Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington. The former was a wealthy philanthropist and admirer of the latter.

Washington believed that self-help and education among African-Americans was the best means of improving their communities, and that after a period of improvement, they could challenge inequality by force of their economic viability and social indispensability.

Rosenwald, a part owner and top executive of Sears, Roebuck and Co., took the notion to heart, and with Washington launched a grant program that funded African-American schools. By 1932, when the last of them was built, close to 6,000 Rosenwald schools stood throughout the South, 800 of them in North Carolina alone.

The qualifications for receiving a Rosenwald grant were simple: The building had to match Rosenwald specifications (the foundation provided many potential building plans; Mars Hill used Plan 20, according to Reker), and the community and school district had to furnish part of the funds.

Starting in 1930, all African-American students in Marshall started being sent and ultimately bussed to the Long Ridge Rosenwald School. This was the situation when Omar McClain, a Marshall native, attended from 1950 to ’54.

“I’m one of those people that caught that little yellow 10-passenger bus,” McClain says. “They would come and pick us up from Marshall, and I didn’t really realize … the sacrifice that [the bus driver] made — the driver was one of my classmates. If I had to get up at five in the morning, what time did he have to get up? ‘Cause he had to drive all the way to Marshall and back.”

The school taught eight grades in two classrooms: first to fourth in one, fifth to eighth in the other. The teacher “was juggling all these people at the same time,” says McClain. “Each grade would have their own stuff.” Younger kids sat in front, and the teacher started the mornings with them. “They’d do their little thing, and then she’d move onto the next.”

Preserving history

In 1965, with the advent of integration, the Long Ridge Rosenwald School (known since 1959 as Anderson Elementary) closed for good — 11 years after Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, declared segregated public education unconstitutional.

The Madison County school system maintained ownership of the building, but no one seemed sure how to use it. It served as a sometime recreation center, basketball court and even a tobacco barn, but nothing lasted, and for decades the building just sat there as nature moved in to claim the husk that remained.

Perhaps it would have stayed on this path until it completely disintegrated. But in 2003, a neighbor wishing to expand a road that passed by the school from his property asked the Board of Education to demolish the building. The board refused, and a long conversation ensued about what to do with it.

In 2009, an informal committee of school alumni formed with an eye on preserving the school in some fashion. As the push grew and other community members joined, it became the Friends of the Mars Hill Anderson Rosenwald School in 2011. With help from volunteers, the group began clearing the property of debris and making repairs to the building.

“They are rehabilitating it, not restoring it,” notes Reker. “To ‘restore’ it means returning it to its original use. That can’t happen, for obvious reasons.” Rehabilitation, however, still means that the building, to garner governmental protections, must look exactly as it did before, right down to the materials used; the few exceptions are modern features such as handicapped access and air conditioning.

When the rebuilding is complete, organizers say they may turn the facility into a full-fledged community cultural center — but whatever form it takes, it will be one that forever preserves and shares the story of how black students and teachers persevered in separate and unequal times.

Of course, there is much work remaining before that can happen. At present, it’s estimated that $130,800 is still needed to finish the project, including new windows, siding, floors, wiring, paint and HVAC.

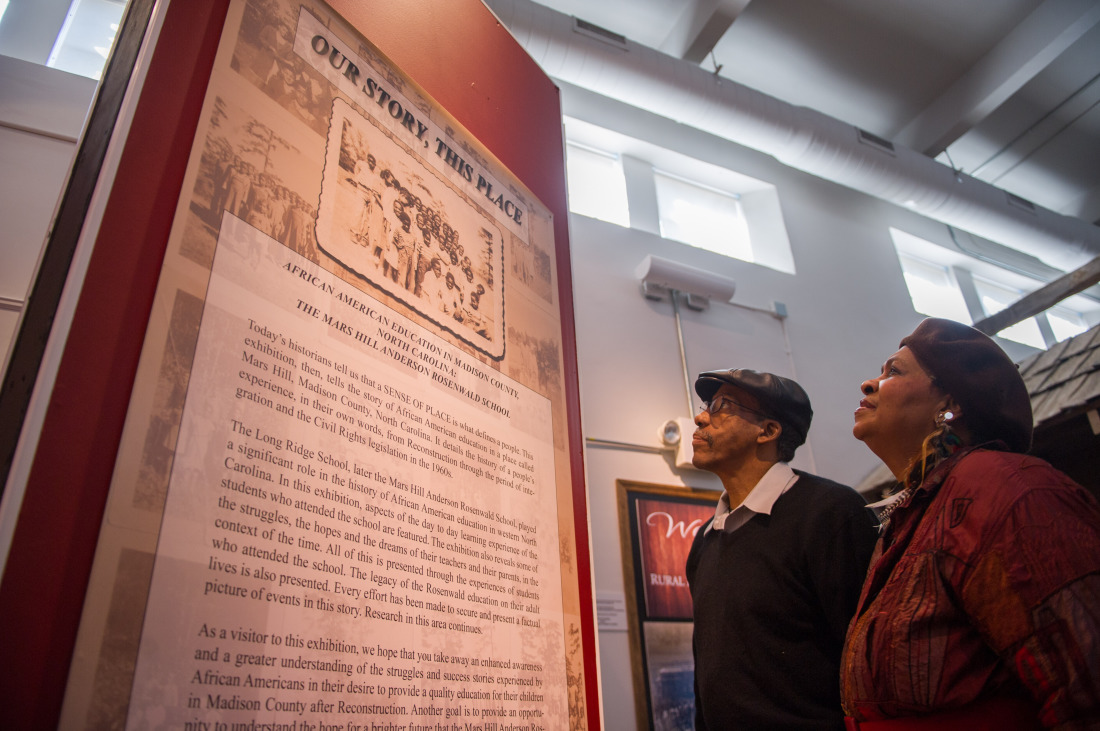

But publicity and support for the effort have been growing, bolstered most recently by Reker’s historical efforts and a series of panels on the school, hosted by Mars Hill University and featuring many of the Rosenwald School’s alumni. In September, the university’s Rural Heritage Museum opened an exhibit, Our Story — This Place, devoted to African-American education in Madison County and using the former school as a focal point.

“It became apparent,” says Reker, “that this was a very important, yet largely unknown, story that occurred right here in Western North Carolina.”

The exhibit, which will remain open through the end of February, houses numerous school artifacts, and massive panels feature blown-up photographs and facsimiles of many newly discovered documents pertaining to the school. “These documents reveal the decision-making that occurred over the years with regard to segregation,” says Reker.

Perhaps the most significant excerpt of a public record on display reads, in part:

Madison County Board of Education Meeting

June 1, 1964 9:30 p.m. …

Action: Consider Geraldine Griffin’s written request to place her Child in the Mars Hill “White” School?/Consider requests by other parents.

Action: Approved

School days

In extensive interviews with Mountain Xpress, four of the school’s alumni recounted in detail just what it was like to attend their Rosenwald School.

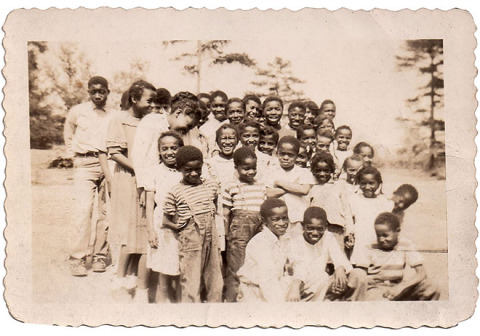

Dorothy Coone and her sister, Charity Ray, lived nearest, in Mars Hill part of the time — during which their father usually drove them to school — and then in Long Ridge, at which point they walked. McClain, as mentioned, took the bus from Marshall. Fatimah Shabazz was from Asheville, and attended the school because her mother, Mary Wilson, was a teacher there.

Wilson ended her teaching career in 1953 as a 14-year veteran of the school; close to an entire generation learned in her classroom, where she taught grades one through four. “It was kind of like she was on roller skates,” McClain recalls. “She didn’t do much teaching from the desk.”

The older students, says Ray, were there to help out if Ms. Wilson was occupied. The atmosphere was ever-orderly, Coone says. “You didn’t really have any disturbance in the room, even with four different grades.”

And if there was any misbehavior? “We got two different degrees” of discipline, McLain says with a laugh. “She’d do your hand with a ruler if you did something minor. But if you broke the cardinal rules or something, she had a little Bolo bat. She’d bend you right over them chairs and bust you right out there. It wasn’t … violent, or even painful. But the embarrassment was unbelievable. You’d cry just because you were embarrassed.”

“It was either a switch or ruler when we went,” says Coone. “Girls didn’t get switched,” Ray adds, smirking.

There were three rooms in the building. A parlor “where we hung our little cloaks,” says Shabazz, and the two classrooms. In the center, on the windowed side, was a brick chimney. A sliding partition ran from the chimney to the other wall, separating the classrooms. Two pot-bellied coal stoves were connected to the chimney, one in the corner of each room. One student was designated “fire-keeper,” responsible for lighting the stoves before school started and feeding them coal throughout the day.

Down below the school was an outdoor privy, which served as the restroom until the school got plumbing in the late 1950s. There was one spigot outside that all the kids used to wash their hands.

School started at 8 a.m. and went until 3 p.m. Lunch was around noon, with recess right after that. Each day, Shabazz says, began the same way: “You come in, hang up your coat, sit down and have devotion — singing a song, reciting a scripture by memory and doing the Pledge of Allegiance.”

The coursework was very much up to the discretion of the teacher. Students learned the basics — reading, writing and arithmetic — but McClain recalls other lessons catered to local living conditions. “Our curriculum dealt in the world,” he says. “We had studies on leaves and vines … what you could grab or not grab, what to eat or not eat. Most people lived off the land … and I think that it contributed mightily to the longevity of the people.”

One of the obstacles to learning was the state of the classroom materials, books in particular. The school couldn’t afford new books, nor did the school system provide them, so all books were secondhand, with some in better shape than others. “We didn’t get any new things at all,” says Coone. “And part of the book would be there, and the other part wouldn’t.” Shabazz recalls getting hand-me-down texts from public libraries. “Whatever kind of books we could get, we read,” she says.

Ironically, the students’ lack of access to standard reading materials sometimes ended up exposing them to more-challenging works. “There was Shakespeare, all that,” Shabazz says. Shakespeare, in the first grade? “Yes,” she insists, laughing. “Not only did we read it, but we acted them out.”

Ms. Wilson “was big on classroom participation,” says McClain, as if performing Shakespeare as an 8-year-old were the most normal thing in the world. “Acting it out,” Shabazz continues, “you really can relate more to what you’re reading.

Connecting community

Acting practice and plays the students put on for the community were a big part in a big school tradition, say alumni. Holiday and end-of-year plays were standard, though often there were others throughout the school year, often to fund a class trip or other activity.

“It was an efficient way to raise money for something,” says McClain. The teachers would slide back the partition, and “all the community would come — white, black, whatever. It would be packed with people.”

“The whole neighborhood [came] — sometimes people your parents worked for, [and] even people from uptown [Mars Hill],” says Coone.

Many of the productions were in the nativity vein, especially around holidays like Christmas and Easter. Others were shorter, more like skits.

“I remember one of them we did,” says Coone. “It was about hats.”

“It was ‘hats, hats, hats,’” Ray reminds her, replicating the hand motions accompanying each utterance.

“We got out mother’s hats — the ugliest one,” says Coone. “I also remember one play: we were supposed to be daisies. We had on white dresses our mothers made, and they made the hats out of construction paper. … And we had a choir, so we’d sing.”

“Ms. Wilson had an act for getting the word out,” says Ray. “She could really get people to come.”

“It was kids that put on the play, but it was a community effort,” says Shabazz. The tight-knit local neighbors played a huge role in the lives of the students. “The community raised the children as much as the parents,” she says. “When we got out of school, we didn’t have to worry about going home. If nothing else, we went to someone else’s house until someone was home to meet you. Safety and security was big.”

“All the families knew each other,” Coone says. “Most families were large, had eight or nine children. I think we were the smallest group with just three girls.”

“Everybody knew everyone’s comings and goings,” says Ray. “It was a way of protecting one another.”

“When I was a kid, I actually thought everyone on that ridge was related to us,” says McClain, “because the trust was there. I remember, both my parents were working at the time, and I stayed with this white family at the house next to me,” he adds. “But they cared about me.”

Racial matters

All four alumni describe a relatively peaceful racial situation in Mars Hill and the surrounding countryside, even as the Civil Rights movement ramped up in the 1950s.

“The people who lived near me, there was never that racial thing going on,” says McClain. “It just wasn’t that way at that time. When my grandmother’s house burned down in Marshall, the next day, black and white, they were rebuilding that house. They just jumped in.”

Virulent racism “wasn’t a pertinent way of being” in that part of Madison County, Shabazz remembers. “The mindset of the community [was] it didn’t really matter. Everybody took care of everybody else.”

“Mostly it went well,” Coone says of the racial dynamic. “You might have some people, but they usually wouldn’t let you know. The blacks here wouldn’t have stood for it. They’d let you know right then what they thought and it would never come up again. To me, the smaller town is better because everyone knows each other. Half the time, their parents grew up with your parents.”

Ray, describing interactions with white school-age peers, says: “If you got the best of them, they started getting nasty, so you just clobber them one. It didn’t mean your friendship would end tomorrow — you’d play together again, but the name-calling wasn’t there anymore.” Still, she says, “Our playmates would ask our parents why we couldn’t go to school with them.”

“I think it had to do with the economic level,” says McClain of the state of black/white relations. “It was basically the same. We were all on the same level. No one could point down to you.”

Both McClain and Shabazz hint that there was a certain feeling of normality to the situation — that segregation was just the way things were, and thus went unquestioned. “When we were in school, there was no time devoted to racial disharmony,” says Shabazz. “They did teach us about Booker T. [Washington] and Frederick Douglass,” says McClain. “At the time, we thought there was only two black men who ever did anything.”

“I don’t think any of us knew the history of that school (Rosenwald) or how it all came about,” Shabazz adds.

“It was always there,” says McClain. “My mother went to that school. We just all thought it was always there.”

But even if Mars Hill was relatively accepting and safe, the kids were schooled in a segregated setting and could not escape the broader cultural landscape. “I knew racism existed,” says McClain. “Because every now and then someone would holler out a window or something. When we traveled, or pulled up in a diner, we couldn’t go in the front and eat, we had to go around and get the food to go, where people would wash the dishes or whatever.”

Shabazz in particular has a unique perspective on racial matters during her childhood. As a native of Asheville, she attended the Rosenwald School with an outsider’s view to the interactions in Mars Hill; she, too, contends that it was “a little different” in the rural community.

Mars Hill “didn’t carry that torch as much,” says Shabazz. “In the city [of Asheville]? Yeah. I was aware of the lack of respect around my mom and dad, which really upset me as a child.”

Indeed, no matter how ideal Mars Hill was or wasn’t, it only took a half-hour trip south to the Land of the Sky to find the indignities.

Major department stores and other locales, they recall were particularly problematic, and the memory got a rise out of McClain. “Let’s don’t go there. White and black water fountains.”

“White and black bathrooms,” says Shabazz. “Yep. And where Diana Wortham is, there used to be a theater called the Plaza, and we went in on Market Street.”

“Around the corner to go in,” says McClain.

“Up to the balcony,” says Shabazz. “And then we’d throw things down on your heads.”

During high school, meanwhile, most Madison and Buncombe county African-American students attended Stephens-Lee in the East End neighborhood of downtown Asheville (Coone and Ray both attended Allen, a private high school for African-American girls, also downtown).

African-American students from Madison had to do this because there was no black high school in Madison County. For a long time, those students had no option to go to high school at all — Stephens-Lee was, after all, way out of district.

And before North Carolina raised the mandatory age for school attendance to 16, with no high school for them, this meant that many black children in Madison who finished 8th grade at the Long Ridge Rosenwald School would simply have to repeat the 8th grade over and over until they turned 16.

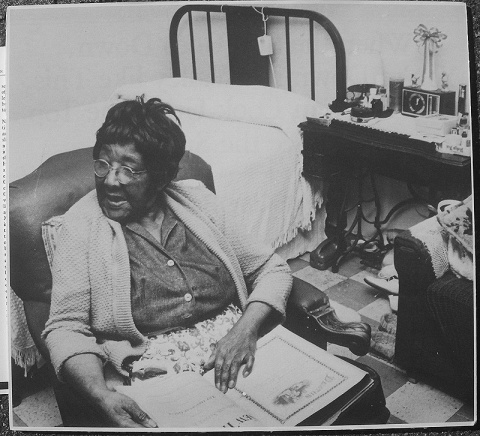

Mars Hill native Viola King Barnette was instrumental in getting this changed — so much so, Reker says, that she’s considered a “crusader for black education.” King, a domestic worker whose son Herbert attended the Long Ridge School, wrote the North Carolina Department of Education to request that schoolchildren from the Long Ridge school be bussed to Stephens-Lee after 8th grade. The state superintendent responded in the affirmative, paving the way for McClain and many other Madison natives to attend high school when they otherwise wouldn’t have been able.

McClain and Shabazz both light up when speaking about their time at Stephens-Lee.

“[Lee-Edwards High] were our rivals,” says Shabazz. “We used to kick their butts in football.”

“And when they had the [holiday] parade, our band was the toughest around,” says McClain.

“Man, our band was bad,” says Shabazz, meaning they were “so [awesome] that initially we used to be up front or in the middle [of the parade]; but people would just start leaving [after we passed], before Santa Claus came!”

“So they put us at the end, to make everybody stay,” McClain adds.

“I remember being on Asheville Avenue one day,” says Shabazz. “And this gentleman was chewing tobacco, and he did this ptch-chew spitting kind of thing ,and he said ‘I ain’t leaving till Stephens-Lee gets here.’ You can check the history, but it happened: Our band brought in Santa Claus, because [otherwise] people would leave.”

“I had a good time at Stephens-Lee,” she continues. “At Asheville High? No.”

Shabazz is the only one of the four that experienced integration while still in school. She spent her senior year at the new Asheville High School, which integrated Lee-Edwards and Stephens-Lee. It would prove to be her least-favorite year of schooling. “Our class was the first to have integrated teachers,” she says. “And a lot of teachers at Stephens-Lee lost their jobs. “All highly educated, all had Masters [degrees].”

“They didn’t want to take a pay cut,” says McClain. “And rightfully so: they had degrees, why should they have to take a pay cut?”

“I know I went to a meeting in Asheville,” says Ray. “And they were discussing equal rights, and these were supposed to be educated people. They weren’t from way out [in the country]. And one lady says, ‘You all just have to give some of us time to love you.’ And I said to her, ‘Your love is not worth a dime. What we want is equality. When we go to work someplace, we want to get paid equally.’”

Ray pauses a moment, thinking. “I guess that lady has grandchildren by now. Maybe she learned to love or something. But I didn’t hold it against her. I don’t think she realized what she was saying.”

Homecomings

All four Rosenwald alumni left Western North Carolina after their schooling, and all eventually made their way back.

McClain joined the Army after graduation. After leaving the service, he moved to New York, embarking on myriad enterprises: “I went to college there, worked on Wall Street, owned an inventory business, and at the end I owned a nightclub.” But tiring of the “rat race,” McClain says, he returned to Western North Carolina in 2008.

After her tumultuous senior year at Asheville High, Shabazz migrated to the West Coast. “I swore I would never come back,” she says. She lived in California, Virginia and Atlanta, for the most part keeping her distance from her hometown. In 1993, she had to return to take care of her parents, arriving just when the infamous blizzard hit. “It’s like God was saying, ‘You ain’t going nowhere,’” she recalls.

The Ray sisters departed as well. Charity wound up in New York. After working there for several years, she returned home to take care of her ailing father, and stayed. She got a job at Mars Hill College (now Mars Hill University) as a circulation assistant in the campus library, a position she kept for 39 years.

Dorothy went to Virginia, working for a bank as a credit analyst. After her husband passed away, she returned to Mars Hill to help take care of her mother, and she, too, decided to settle. The sisters live together in the house they moved into in the 1940s, the one that made it possible to walk to school.

All four have been intimately involved with the rehabilitation campaign. When it started, Ray recalls, “We said, ‘This school is still standing.’”

“Separate but equal” was always a lie, but that just makes the quality of education in the Rosenwald School all the more remarkable.

“When we went to Asheville schools from Mars Hill schools, there was this thing like we aren’t supposed to be ready, because we came from a rural school,” McClain remembers. “But most of the teachers were vested in our future, either by relationship or family. It seemed like they put a little more into it to make sure each person was prepared. We were more than ready.”

i was thrilled to read this story . i am in the welcome center in hot springs a few days a week and i would love to know more of Madison county’s black history. who should i contact to speak to face to face with questions? thank you , babz, covington