Ten years ago, Asheville City Schools displaced Randolph Learning Center — its once-successful majority-Black alternative program — from its home on Montford Avenue. Asheville High School Principal Derek Edwards has called it the worst decision ACS has made in his 20-plus years in the district.

Soon, the district may be poised to give its long-transient alternative program, now called the Education and Career Academy, a permanent home at the same site on Montford Avenue.

While discussing the consolidation of Montford North Star Academy into Asheville Middle School, it came up that the building would be a good home for the ECA, which serves students who are unsuccessful in a traditional school setting. The Asheville City Board of Education subsequently voted March 11 to consolidate the two middle schools next school year, freeing up space for ECA to potentially move from its temporary home at the Housing Authority of the City of Asheville’s Arthur R. Edington Education and Career Center on Livingston Street.

The state requires each district to have an alternative program for high school students who are at risk of dropping out of school. As Edwards, who taught math at RLC, said at a recent school board meeting, that program could be anything from a computer in a room to an entire campus.

“We’ve got to figure out what we’re going to do for our alternative education. What is it going to look like? Because we have had everything under the sun in this district,” Edwards said at the March 4 meeting.

A glaring mistake

Indeed, in ACS, the program has been on a journey over the last 20 years. In 2003, RLC was established in the William Randolph building, named after the first secretary of the Asheville school board, according to newspaper archives. Back then, the school operated in a space shared with a college preparatory public charter program, the KIPP (Knowledge Is Power Program) Academy at 90 Montford Ave. Later, after KIPP closed, RLC had the space largely to itself.

During its years at Montford, RLC flourished, according to those who taught there, and became an independent school within the district. RLC’s golden years lasted until its innovative leader, Principal Gordon Grant, was moved by the district to lead Hall Fletcher Elementary in 2011. Two years later, the program was relocated to modular trailers on Livingston Street near the present-day Wesley Grant Southside Center to allow Isaac Dickson Elementary School to occupy 90 Montford Ave. while its own campus was renovated nearby.

Black mold was found almost immediately in the trailers, says former RLC teacher Kimberley Fink Adams, and its students were dispersed into shared spaces at AHS and AMS. Since then, the program has moved at least two more times and churned through three different names, landing on the current Education and Career Academy in 2022.

In hindsight, Kim Dechant, current chief of staff and district spokesperson, acknowledges the glaring mistake of moving the school into trailers.

“I think as we work through our equity work, and as we have grown, we can definitely look back and say that was wrong. Out of the gate, that was wrong on so many different levels, to put our most vulnerable students in modular [units],” she says.

Especially in a district that has struggled to sufficiently educate its students of color, including having the largest disparity between white and Black students’ academic proficiency of any district in the state as of 2017, leaders say a strong and stable alternative program is vital.

For 10 years, say multiple teachers who worked there, the Randolph Learning Center provided that stability, serving kids who would have otherwise dropped out of school.

“We absolutely saved lives. There were tragic circumstances that some of our students came out of,” Edwards said.

A last resort

In its heyday, RLC operated as both a last resort for kids who were on the verge of dropping out and a school of choice for others who were struggling in the traditional classroom setting, says Grant, who is now retired.

“Often the school would say, ‘This kid is really struggling, they’re behaviorally acting out, they’re academically underperforming. They’re not successful here, and they’re not helping other people succeed.’ Or the parents could request that they come to us. And that was the angle we really pursued in my five years there: We reached out to parents,” he says.

Parents and students bought into the school’s project-based, experiential teaching style. More than trying to get kids to learn a predetermined curriculum, teachers worked to incorporate math, English and science lessons into real-world projects, Grant says.

There was a greenhouse on campus and a recording studio run by LEAF Global. Nonprofit Green Opportunities focused on teaching skills that would translate to jobs in the green economy, as well as cooking skills. Grant collaborated with UNC Asheville to get college-age tutors.

The school hosted a family meal Thanksgiving week, wherein students brought family recipes in, and Edwards, a math teacher at the time, would teach them how to scale them up to feed the whole school, Edwards said at the March board meeting.

The school also held regular cookouts and other “culturally respectful” events that created an atmosphere where Black families felt welcome, further developing trust, says Eric Howard, former lead social worker at RLC.

Grant took students on field trips as much as possible to expose his students to things they would otherwise never have the chance to see.

“We treated our kids like they were at an elite private school,” Grant says.

On Halloween, students visited Riverside Cemetery to get inspiration to write scary stories, says former RLC English teacher Cedric Nash.

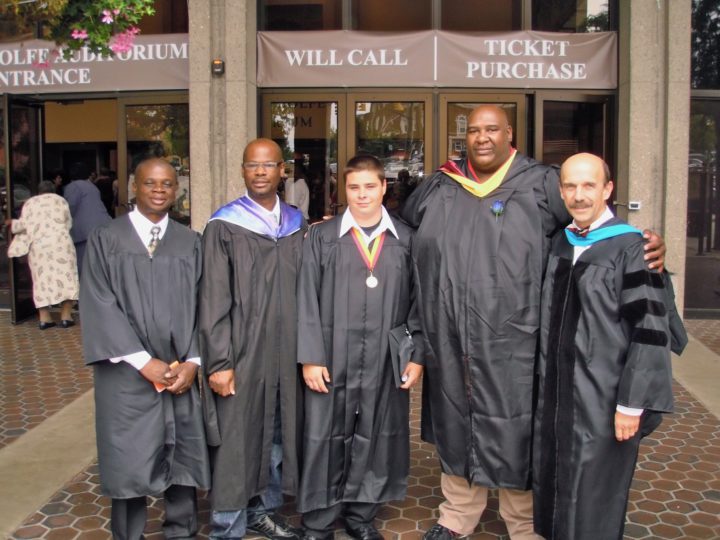

Students did science days at Carowinds and Pisgah National Forest. They went to N.C. State University for a future cities competition. They got to experience horse therapy at a farm and learned history at the Vance Birthplace in Weaverville. Local jazz artists came to the school to teach music to students. Nash wrote a grant and took four students to see jazz great Wynton Marsalis at the Thomas Wolfe Auditorium, he says.

“They would not have gotten that any other way,” Nash notes. Outside of the public housing communities many of RLC’s students lived in, the Asheville Mall was just about the only place any of them had seen, Grant says.

“The majority of Black citizens at that time were very isolated,” adds Howard, who goes by “Big E.” “People weren’t paying attention to this demographic of kids very much, not only in the district but communitywide.”

The school also provided some structure and was the only one in the district to require uniforms — green polos and khakis.

Randolph operated a suspension center where students who received, for example, a 10-day suspension from AHS or AMS, could go to get a meal, supervision and academic instruction.

Family atmosphere

Above and beyond academics, the school, which ranged from about 90-125 students, on average, provided extra attention and care to students who may not have felt supported in a larger school setting.

“At the end of the day, Randolph was so important because you had a group and a team of individuals that were so laser focused on this specific group of kids. You gotta love them kids every day, man. Like, you just gotta love them no matter what — no matter what they do or how they behave. You gotta let them know [that you’ll] be there for them no matter what. And so our team did a really good job of that, of loving folks and making sure that they were OK, making sure that they were supported,” Howard says.

Nash, who is now an assistant principal at a high school in Georgia, says relationships are the most important part of education, and he spent a lot of time sitting in living rooms and around the dinner table building connections with families during his time at Randolph.

“It was about caring. As educators, we were not afraid to have hard conversations, get in our car, drive over to Hillcrest, Lee Walker Heights or Erskine, and talk with a parent. If a parent could not come to us, we went to them,” he says.

Howard, Nash, Fink Adams, Edwards and Randall Johnson, the current director of the Education and Career Academy who used to teach at RLC, all called their time at Randolph some of the best in their teaching career.

Much of that credit goes to their leader, Gordon Grant.

“I love this man. He has been my biggest educational advocate and one of the biggest mentors I’ve had in my career,” says Howard, now the head of Odyssey School, a North Asheville charter.

Howard and Nash both say Grant believed that they would succeed, something they hadn’t gotten much as Black men working in a predominantly white district.

“Randolph taught me a great deal about leadership. I give that to Gordon Grant. I learned a lot from him. I learned a great deal of how to work with parents and students. Be forgiving when you have to be forgiving, be lenient when you have to be lenient. Give second and third chances at times,” says Nash, who grew up in public housing in Asheville before joining the Army.

Grant was able to build such a family atmosphere at Randolph through empowering all staff, including custodians and librarians, to be educators, he says.

The cultural shifts helped the students, too. Disciplinary referrals from teachers at Randolph went from 1,000 in its first year to 100 the next, according to Grant. The school’s dedicated resource officer, initially posted daily at Randolph, went back to the high school in its second year because his services weren’t needed, Grant adds.

“We really reduced it a huge amount, because the kids started to perceive that they were welcomed there, that it was a place where they would be respected and treated well,” Grant says.

“It was a beautiful experience. Most kids chose to be there. Even when they were the only ones wearing uniforms at the bus stop, they still chose Randolph because of the care we provided,” Edwards noted at the March 4 meeting.

After Randolph

Unfortunately, the school didn’t last.

Grant says that at one point, district administrators mentioned to Grant that it was costing the district more per year to operate his school than others, which he didn’t dispute.

“Yes, these kids are going to be expensive. But it’s also going to be expensive if they fail and drop out. You pay one way or the other. I love that bumper sticker that says ‘If you think education is expensive, try ignorance,’” Grant says.

Meanwhile, Hall Fletcher Elementary, another high-poverty school, had a revolving door of principals at the time, and the decision was made to send Grant there. Former AHS Assistant Principal Fletcher Comer was tapped to replace Grant, but he left the system to move to Alabama after a year, according to Grant.

“I was happy to go, but I was really sorry that that meant, essentially, the dismantling of RLC, which then ran into really hard waters,” Grant remembers, calling the decision to move the program into trailers on Southside, the mold and the eventual dissolution of RLC a “terrible debacle.”

“There was a lot of sadness,” remembers Howard. It was “the worst thing we’ve done,” Edwards told the school board.

Howard and Fink Adams both said the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners at the time promised community members they would get their school back.

But after the district abandoned the trailers, middle school students were sent to the basement at AMS, which didn’t work because the already vulnerable students, isolated from the rest of the school, felt unwanted. Before long, students were reassimilated into general education classrooms.

High school students first wound up in AHS’ ROTC building. That didn’t go great either, as students began to feel like afterthoughts, remembered Edwards.

Due to this confluence of issues, including higher-than-average expenses, Grant’s departure, moving the program into trailers and then into several schools, RLC was ultimately dissolved in 2014.

The district twice tried to revamp an alternative program, including programs called AHA and GRAD. No one who spoke with Xpress for the story remembered what these acronyms stood for, further illustrating how neither ever truly gained traction. Part of the problem was they were housed in various rooms or wings of the high school, remembered Carrie Buchanan, an administrator at AHS charged with overseeing the alternative program at the time.

“They feel like aliens on a campus they should feel a part of,” she noted at the March board meeting.

One parent asked Buchanan what the point of an alternative program was if the kids were still located in the large, chaotic environment of a high school.

Students in the program stuck out among the general high school population, even after their uniforms were abandoned. If they left their designated area, a school administrator was immediately called, Buchanan said. They were served meals at different times from everyone else in the school, making them feel isolated.

In 2022, the district asked Johnson, the former RLC teacher, to give a new alternative program, the Education and Career Academy, a fresh start. He jumped at the opportunity.

ECA goals

In many ways, Johnson hopes to re-create some of that magic from the Randolph days at ECA, and he’s had some success already despite a “skeleton crew,” he says.

Nearing the end of its second school year, the ECA has about 30 students overseen by four teachers, a social worker and two administrators operating in four classrooms and a small common room in the Edington Center. While there is value to the school’s location near several public housing developments on the city’s southside, allowing many students to walk to school, sharing the space with the housing authority and several after-school programs is not ideal, Johnson says.

Students must leave by 1:45 p.m. every day to make space for after-school programs, and even teachers must be out by 2, giving them nowhere to plan their lessons. People looking to meet with Housing Authority staff, turn in forms or pay bills often wander through the halls during the day.

During the school day, the school has access to a gym, but there is no media center or cafeteria, and it doesn’t have a custodian or school resource officer, Johnson says.

Plus, the Housing Authority has capped the program at 30 because of space limitations. Johnson says there could be as many as 200 students who would benefit from the program.

Despite all this, Johnson feels the program has been successful in providing students three pillars of service: school credit recovery, promotion to the next grade level and graduation.

Johnson strives to get students prepared for postgraduation job searches so they can immediately be successful in the real world once they’re there.

Part of the success of ECA is its adoption of state minimum requirements for graduation, as RLC adopted years ago. In contrast, AHS requires 28 hours of credits to graduate, while the state requires only 22.

Johnson, who grew up in Asheville’s public housing community, focuses on the “ground zero” needs of students before pushing them academically, he says.

“You are loved, you are someone to be loved, you are someone to be respected. The people around you are to be loved and respected. Learn all you can, be the best you can. Anything you put your mind to you can do,” he says.

He challenges students, many of whom are homeless or without parents, to ask how each action is helping them move closer to their purpose and how it represents or affects their family, he adds.

His approach has earned the recognition of alternative education administrators around the state, 40 of whom will converge on his Livingston Street school in late April to evaluate his program and reflect on how they can adopt his practices into their own programs, he says.

The biggest need for his program going forward, Johnson says, is additional staff and a dedicated space.

The prospect of a new alternative program getting the support it needs, 10 years after it dissolved one of its most successful programs, gives RLC’s former teachers hope.

“So the babies get to go back home to Montford. I hope they have good leadership to help them thrive. There’s nothing like having a home. I’m glad kids are going to have a home,” Howard says.

This article is astonishing. I follow the Asheville City schools fairly closely and am amazed by the lead curtain around it. Real information is very difficult to find. This article has more information that I have ever seen! Amazing and thanks. My input: If the consolidation between the school districts goes through, then the first impacts will be on programs like the Education and Career Academy. Buncombe Co Schools has an alternative program. I would recommend that ordinary professionalism should be a guide to the ACS school Board. Do not stir up a mess that will then have to cleaned up the new, bigger Buncombe County school district.