In the autumn of 1909, Stumptown, a former bustling Black neighborhood near Riverside Cemetery, became the talk of the town when a fence was installed blocking a busy pathway known as Tempe Alley.

After raising complaints to the city aldermen several times, residents of Stumptown demanded the issue be settled in court.

“The plaintiffs will claim that for more than twenty years they have trod that path and toted one thing and another down the hill and up the hill,” The Asheville Citizen wrote on Oct. 20, 1909. “And then they will endeavor to show that this makes it a street and a public highway.”

But the defendant, the paper continued, “will show that another street more suitable may be made and equally as convenient. In all there are about twenty families in the hollow.”

Along with the case’s details, the article offered a brief history of the neighborhood, noting the first Black residents “settled in the hollow under the brow of the hill” in the early to mid-1880s.

Two weeks later, Stumptown resident Squire Kilgore officially filed suit against E.W. Dukes, the man responsible for “obstructing the only available outlet from that region full of gulleys and ravines,” The Asheville Citizen reported on Nov. 2. In addition to demanding the fence be removed, Kilgore was seeking $50 (roughly $1,400 in today’s currency) in damages caused by the closure. Whereas the paper identified Kilgore as Black, it did not note Dukes’ skin color, suggesting the fence owner was white. (The paper also addressed Dukes with the title “Mr.,” while Kilgore received no such courtesy.)

According to The Asheville Citizen, several of Stumptown’s first settlers testified about the path’s long-standing use. “Judge [Henry B.] Stevens then asked that the rest of the evidence be postponed until Thursday as he wished to get several more witnesses and consult some authorities,” the paper concluded.

The Thursday request appears to have extended to the following Tuesday. By that time Judge Stevens had recused himself from the case on account an obvious conflict of interest — he was representing Dukes. Stevens’ replacement, Magistrate W.A. James, took the hearing outside the courtroom.

“This afternoon the old order and traditions of one magistrate’s court will change and give way to another plan for the meeting of justice and the taking of evidence,” the Nov. 8 issue of The Asheville Citizen declared. “Shades of the great juries and legal lights will awake and take notice. Magistrate James at the hour of three will hold court in Stumptown, one of the suburbs of this metropolis, and listen to the evidence in the famous Tempe alley matter.”

The article went on to note Kilgore’s attorney, R.S. McCall, had requested the move to accommodate some of the community’s elderly residents who, due to aliments, would otherwise be unable to testify.

“So promptly at the hour of three with all the dignity of the Supreme court Mr. James will sit on a stump, it is understood, and direct the counsel for both sides in the case for the opening of Tempe alley to proceed with the evidence,” the paper reiterated.

The following day’s account, however, reveals no such hearing took place. “The famous Tempe alley case which had been postponed indefinitely from the magistrate’s court on the square to the impromptu court on the stump in Stumptown, that unique suburb of this city, has again been postponed,” The Asheville Citizen wrote. “The reason for this delay is the illness of Tempe Avery, one of the principal witnesses in the case.”

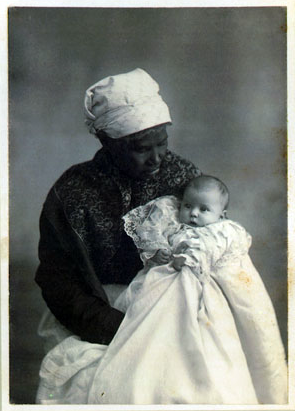

Though the article does not state the pathway was named after Avery, it seems likely the case. Avery, who first arrived in Asheville as a slave became a well-respected midwife and nurse after emancipation. (For more, see “Tuesday History: The Half-Known Life of Tempie Avery,” Xpress, Oct. 17, 2017.)

The Nov. 9 edition of The Asheville Citizen did, however, note a likely decision within the next week about the lawsuit. Yet, as far as this reporter could find (or not find), there is no evidence of subsequent news coverage about the case. Whether the fence was ultimately removed remains a mystery.

Decades later, Stumptown was largely destroyed by urban renewal. Today, woods and the Tempie Avery Montford Center occupy where many of the former homes previously stood.

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original documents.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.