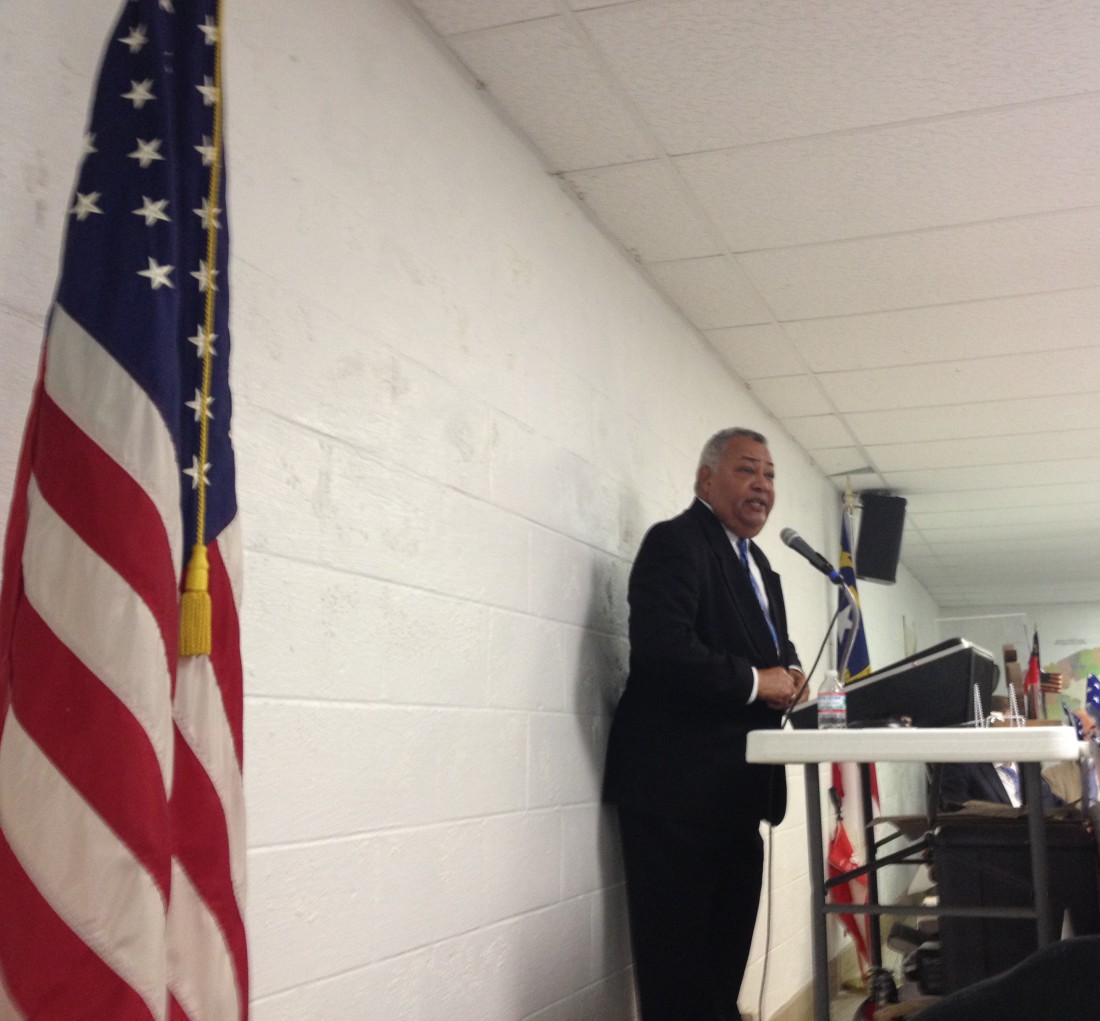

“Like a monstrous octopus, poverty spreads its nagging, prehensile tentacles into hamlets and villages all over our world,” the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. declared in a March 31, 1968, sermon delivered at the Washington National Cathedral. Jan. 16 marks the 30th anniversary of the holiday named in the late civil rights leader’s honor. Xpress took the opportunity to speak with Al Whitesides, Buncombe County’s first African-American commissioner, about some of King’s deepest concerns.

“When you talk about economic justice, I’m not talking about black and white: It’s poor people,” says Whitesides, who was appointed to the Board of Commissioners in December to fill the District 1 seat vacated when Brownie Newman was elected board chair. “That’s what Dr. King realized near the end of his life. He was pushing more for poor people: He understood that in this country, it’s rich and poor. He started advocating for poor people and what they need to move up. That is critical — and more so today than ever.”

In 2015, 37,433 Buncombe County residents — just over 15 percent — were living in poverty, census data show. The county’s median household income that year was $45,642; that was close to North Carolina’s median ($46,549) but nearly $11,000 less than the figure for the U.S. as a whole ($56,516). The median, of course, means there are many households with substantially lower incomes. Some have also questioned the formula used to compute the federal poverty level, but even if you accept the method, there are 43.1 million poor people in the nation today.

“That’s frightening,” says Whitesides. “To have economic justice, we’ve got to get to the point where we’re all playing by the same rules,” he maintains. “But I think we need to understand that in order to get there, we have a lot of barriers we have to remove that stop people from having a level playing field.” Those barriers, he notes, include education, homeownership and decent wages.

In an April 4, 1967, speech delivered in New York City’s Riverside Church, King put it this way: “True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it is not haphazard and superficial.”

Temporary measures

“Just giving people handouts … letting them live for reduced rates in lower-income housing, those are temporary measures,” says Whitesides. “Those measures were never meant to go on for generations. Those were measures to help put people on their feet so they could compete economically in our society.”

King, too, believed that empowerment was ultimately a more viable strategy. “The poor, transformed into purchasers, will do a great deal on their own to alter housing decay,” he said in an August 1967 speech at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference titled “Where Do We Go From Here?”

But current home prices in Buncombe County, notes Whitesides, make buying a house here a lot harder than it was when he first did so back in 1973.

As of the third quarter of 2016, 63.5 percent of Americans owned their homes, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. A deeper look into that statistic, however, underscores the considerable impact of factors like median income, race and ethnicity: 71.9 percent of whites, 47 percent of Hispanics and 41.3 percent of African-Americans are homeowners. Among families with a household income greater than or equal to the median, the homeownership rate is 77.8 percent; for those with lower incomes, the number drops to 49.2 percent.

“That’s where we’re going to have to come together and make a difference,” says Whitesides. “It’s not going to come down from Washington: It’s got to go up from the local communities. That’s why I threw my hat in the ring for this seat: I’m convinced the only way to turn things around in America, especially economic-wise, we’re going to have to start at the bottom and go to the top.”

Increasing access to affordable housing, he continues, is “something that’s badly needed. We can’t continue to do it the way we’ve done it in the past with Pisgah View, Lee Walker Heights, Hillcrest. … We’ve got to do things different. I want to see us put more people in independent housing: mix them up, give them pride in taking care of their houses. That’s the way to do it. If we don’t help people economically, if we don’t make the people tax payers rather than tax takers, we are not going to be successful going forward.”

Priced out

For growing numbers of local people, though, notes Whitesides, finding any kind of housing is becoming ever more challenging. “If somebody’s making minimum wage, they can’t afford to live in Buncombe County,” he points out. “I run into more and more people who live in Madison, Transylvania, Haywood counties and also driving down the mountain to McDowell County because they can’t afford to live here. And that’s something we’ve got to change.” The minimum wage in North Carolina is $7.25 per hour; at that rate, someone working 40 hours a week makes $15,080 a year before taxes.

But even moving farther out won’t necessarily solve the problem. As of the third quarter of 2016, the median monthly rent in the Asheville metropolitan statistical area (which includes Buncombe, Haywood, Henderson and Madison counties) was $1,044, according to Bowen National Research. For a one-bedroom apartment, the median rent was $930 a month, or $11,160 per year. The city of Asheville hired the Ohio-based consulting firm to produce the housing study in 2014; it was just updated in December.

Just Economics, an Asheville-based nonprofit, tracks employers in WNC that pay what the organization says is a genuine living wage for this area. By the end of last year, the nonprofit had certified 337 of them in Buncombe County, though there may well be others that haven’t sought certification. As of the first quarter of 2016, there were 8,875 business establishments in the county, according to the state Commerce Department’s Labor and Economic Analysis Division.

For 2017, Just Economics has set the local living wage at $13 an hour without employer-subsidized health insurance and $11.50 with insurance, up from $12.50 and $11.85, respectively, last year. But even at $13 an hour, someone working 40 hours a week would earn $27,040 a year before taxes, which would still make it hard to afford the median one-bedroom apartment rent.

The 2014 Bowen report showed high and low rent figures as well as the median; for Buncombe, Henderson and Madison counties, the low-end rent for a one-bedroom apartment was $548 a month. That works out to $6,576 per year — a hefty chunk of the annual income for a minimum-wage worker — and those rents would also be higher by now.

Removing barriers

“If a man doesn’t have a job or an income, he has neither life nor liberty nor the possibility for the pursuit of happiness. He merely exists,” King maintained in his 1968 National Cathedral sermon.

And when you look at the last presidential election, says Whitesides, “What happened here was a lot of Americans are hurting and disillusioned with Washington, and they want to see something different. In order to do that, we’ve got to work together. It doesn’t matter if you’re a Democrat, Republican or independent. It’s going to take all of us working together to remove barriers.”

Asked about specific policies he’d like to see implemented at the county level, Whitesides said he’s not ready to show his hand yet. But he added, “I’m not there to keep a seat warm: I want to get something done.”

LOL, but democrats view the blue collar person as inferior. Yet they extract that persons’ wages for their own gain because they can’t earn the money themselves.

How many millions of $$$ can be saved per year by Buncombe County TAXPAYERS by consolidating the unnecessary two system operations ? WHY do our county commissioners NEVER bring this up for discussion? ALL ONE system means greater diversity for ALL the students and the savings will be a big bonus to the taxpayers. ONE school board, ONE superintendent, lots of duplicate jobs eliminated. Makes nothing but good sense! When ?