Asheville’s once-neglected South Slope neighborhood has become the city’s trendy spot to grab a beer, drive in circles looking for parking and succumb to the allure of gentrification. But amid the seemingly endless proliferation of craft breweries and construction projects, one organization continues quietly working to revolutionize North Carolina’s mining industry.

For 70 years, the Minerals Research Laboratory on Coxe Avenue has collaborated with mining companies and educational institutions to develop more efficient processes for extracting the state’s mineral resources as well as ways to reuse potentially harmful byproducts.

Pointing the way

Robert Mensah-Biney’s low-key manner fits the profile of the research facility he’s overseen since 2012. Soft-spoken and affable, he has an encyclopedic knowledge of local minerals.

The lab, originally a joint initiative of the Tennessee Valley Authority and N.C. State University, was founded in 1946; TVA’s involvement ended in 1950. The facility’s mission, says Mensah-Biney, is threefold. The crown jewel is a pilot plant, the only one of its kind in the United States, with a variety of equipment that can be moved and adjusted to fit the particular project’s needs. This enables engineers and interns to calculate the amount of time and materials needed as well as the cost of building and operating a full-scale version of such a processing plant. The resulting data is then shared with the mining company that commissioned the research.

The lab also provides analytics and technical support for state-sponsored projects aimed at expanding North Carolina’s mineral industry, such as the integrated phosphate mine and chemical plant in Aurora.

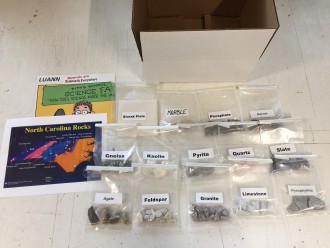

Additionally, the mineral lab provides educational opportunities for kindergarten through college-level students around the region. Besides assembling and sending out free rock sample kits, DVDs and posters to teachers around the Southeast, the lab hosts field trips and does outreach in classrooms, senior process engineer Hamid Akbari explains.

In 2008, the research facility partnered with UNC Asheville to create a mineral processing curriculum. “We‘ve had 50 to 60 students go through it,” Mensah-Biney reports. “Next semester, I’ll be teaching a course in flotation,” a method of separating the minerals in ore.

The hard rock cafe

The Coxe Avenue facility’s work provides key support for one of the state’s least heralded but economically significant industries. “As of 2000, there were over 700 active mines in North Carolina,” notes Mensah-Biney, citing the most recent survey of in-state mining operations. That same year, he continues, “The annual sales from mining here were about $800 million, and the estimated employment was over 100,000.”

Those operations focus mostly on industrial materials such as mica, olivine, pyrophyllite, feldspar, sand, gravel and phosphate. Spruce Pine, for example, is the world’s No. 1 producer of high-quality quartz, which is used in electronic devices such as cellphones and computers.

“We are a linchpin in the global technology industry,” says D.J. Gerken, an attorney with the nonprofit Southern Environmental Law Center. “In 2004, when the hurricanes came through and access to Spruce Pine was temporarily shut down, apparently there was a freakout in Silicon Valley because their supply got disrupted.”

Monitoring the mess

But while the environmental impact of North Carolina’s mining operations pales compared with the havoc wreaked by mountaintop removal and hydraulic fracturing in other areas, excavating minerals can still adversely affect the surrounding ecosystem, says Gerken.

“A lot of the mines are old industrial operations,” he explains. “Like any old industrial operation, you can have old problems that have never been fixed.”

In Western North Carolina, those problems include runoff contaminating sensitive waterways, toxic chemicals embedded in the rock that are released during excavation, disruption of natural hydrology when fill is dumped in watersheds, particulates in the air and pollution associated with operating heavy machinery.

Once a mineral is extracted, the runoff of “spoil” materials left behind can have devastating effects on aquatic life, says French Broad Riverkeeper Hartwell Carson. “It smothers the habitat, clogs their gills.” A few years ago, he continues, a fisherman in the North Toe River “was burned by some of the runoff.”

Citizen groups like the Toe River Watershed Partnership, notes Carson, can help ensure that mining companies are living up to the terms of their permits.

“The public, particularly in Spruce Pine, started noting when the river would turn white from too much runoff and began calling the state and the mine directly,” he recalls, adding that residents can also weigh in when mining permits are up for renewal. “If a permit’s no good, then you can discharge a lot of pollutants without breaking the law. I think there will be some opportunities for public engagement in the coming months or year.”

Balancing the needs

Coal isn’t mined here, but burning it in power plants also causes problems.

“There’s a coal ash crisis in North Carolina that’s been going on for years,” says attorney Frank Holleman, a colleague of Gerken’s at the Southern Environmental Law Center. The advocacy group has pressured Duke Energy and other utilities in the region to clean up the ponds where the ash is stored. Last March, Duke agreed to a $7 million settlement of groundwater contamination issues at all 14 of its coal-fired power plants in North Carolina.

”Then we had the explosion of public concern when Duke — while denying all the issues we were raising — was proven not to be telling the truth about its Dan River site in February 2014,” Holleman continues. In one of the worst such spills in U.S. history, a broken stormwater pipe sent massive quantities of coal ash and contaminated water into the river.

Since then, he says, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency officials have stepped up their monitoring of companies like Duke. But at the state level, Holleman asserts, “The regulatory agencies have done a pathetic job. What is now called the Department of Environmental Quality has been, if anything, a negative force: For the last four years, it’s actually fought citizen law enforcement under the Clean Water Act and opposed excavation of ash at some sites that Duke and the environmental groups had agreed needed to be cleaned up.”

Environmental regulators, Gerken maintains, are under intense pressure from powerful lobbyists in Raleigh and Washington, D.C., to overlook violations. “When you have an important industry, it’s so tempting for the regulators to give them a pass. We’re certainly very happy to see people in WNC having jobs in productive industry, but we feel strongly that you have to do it well and balance it.”

Lessons learned

Asked for a response, spokesperson Danielle Peoples said: “Duke Energy immediately accepted responsibility for the release and undertook immediate and ongoing actions to address it and provide notice to appropriate governmental authorities. We were operating in full compliance with our NPDES [National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System] permit prior to the release and had been undertaking regular inspections of the ash pond dikes as required. The failure of the pipe was sudden and unintentional.”

Since then, continued Peoples, Duke has taken the lessons learned from the Dan River incident to make sure the company is complying with new state and federal laws regulating coal ash storage and disposal, while working to close old storage ponds around the state.

“When you think about the history of coal ash management for over a century now, the industry has been continually improving as new technologies and additional research becomes available,” she pointed out. “I am proud to work with a team of dedicated professionals who are always looking for ways to improve the way we manage ash. At the core of it all, SELC is advocating for the same things we are working hard on every day: continued safety and protection of our communities, environment and resources.”

Science vs. politics

The Minerals Research Laboratory has also played a role in identifying potential uses for coal ash. Over the past decade, Mensah-Biney and his team have worked with Duke and others to develop innovative solutions for dealing with the byproduct.

Coal ash, stresses Holleman, “is not a resource: It’s a waste.” But he supports genuinely safe recycling methods, noting, “There’s no evidence of any leaching over time of the byproducts in concrete. If the ash can be used in any responsible way, we embrace that.”

From 2000-06, Mensah-Biney led a consortium of utility representatives, Land of Sky Regional Council staffers and academics that explored cost-effective ways to reuse coal ash in construction materials.

The researchers extracted carbon from the coal ash for use in steel production; the remaining material would be used to make concrete. “We were proposing a process where you can reduce the carbon and then sell the ash to the concrete people to use right now,” Mensah-Biney recalls. The proposed plant, he notes, would have been able “to treat about 1,000 tons a day, so over 300,000 tons a year.”

Ultimately, however, Duke opted for other ash-removal strategies.

“I’ve had to give that up,” says Mensah-Biney. “I can understand the viewpoint of these companies: The majority of the public doesn’t understand it. My concern is, if you’ve spent all this money for research, why wouldn’t you educate the public and tell them this is what we can do?”

Ramping up recycling

In an effort to do just that, notes Peoples, Duke has created an ash management webpage (duke-energy.com/ash-management), with “lots of materials, resources and videos. We seek to share this information with the public and our plant communities as often as we can.”

Duke Energy, she continues, employs an entire team dedicated to evaluating and implementing reuse opportunities. In 2016, the company recycled “more than 80 percent of the ash and other coal combustion products produced at our plants.” Those waste products became components in concrete, cement, wallboard and “structural fills” such as the one at the Asheville Regional Airport’s ongoing land reclamation project.

Under revised North Carolina law, Duke is required to make at least 900,000 tons of ash available for use in the concrete market annually, says Peoples. “To do this requires a large investment in technology designed to reprocess coal ash from basins and make it more suitable to recycle into concrete products. Often, coal ash contains too much carbon to be used as aggregate material in concrete.”

In the coming years, she adds, new technologies will enable the company to expand its recycling capability. The company recently conducted a study with the Electric Power Research Institute focusing on Thermal Beneficiation technology and its potential to improve ash characteristics for reuse purposes.

In October, Duke announced plans to install recycling units at three sites in North Carolina, including the retired Buck Steam Station in Rowan County and the H.F. Lee Plant in Goldsboro. The third site has not yet been named, but Peoples says Duke is “evaluating all of our sites based on proximity to market demand, transportation costs, quality of ash” and other factors.

“We do work to recycle as much material as we can, but this is driven by many factors, including market demand, quality of ash and transportation costs,” Peoples explains. “Ultimately, we seek to make investment and recycling decisions that benefit our customers.”

Either/ore

Meanwhile, the lab is continuing to develop new ways to reuse other mining waste products, such as quarry “fines” (small particles left over from aggregate production), and reduce the need for cement, a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in concrete production.

The research facility is also exploring the feasibility of exploiting the sizable lithium concentrations found around Kings Mountain. “North Carolina has the best lithium ore in the entire United States,” says Mensah-Biney. “We used to produce all the lithium in the country.”

Those mines shut down because they couldn’t compete with cheaper and easier-to-process South American ore. Now, however, Mensah-Biney hopes to develop a pilot program that would make North Carolina’s ore competitive again.

“The lithium from North Carolina is lithium silicate, which needs to be processed to get the lithium carbonate they use for making batteries,” he notes. In partnership with the U.S. Geological Survey, says Mensah-Biney, “We want to start new mining of lithium here.”

Yet another point of interest is the abandoned Tungsten Queen Mine in Vance County. “The tailings have this nice quartz, and we’re trying to process that so the material can be used for solar cells, LED lights,” he explains. “That’s an inactive hazardous waste site right now. We want to help clean that up and recover those materials.”

Essential aggregate

The lab, though, is not some top-secret, off-limits facility, notes Mensah-Biney. “This is your building: You can walk in, ask any questions, take a tour. We’re happy to help.”

And with exciting new projects on the horizon, he believes the lab will continue to play an important role. “What we do is special: We’re the only facility in the United States that does what we do, solely on industrial minerals.” North Carolina’s mining operations, stresses Mensah-Biney, make an invaluable contribution to modern life.

“People don’t look at it that way, but aggregate is more important, mineral-wise, than almost anything else. If you want to build a house, the concrete comes from aggregate; if you’re installing a plant, you need a foundation that comes from aggregate. Roads — aggregate; sidewalks — aggregate; airports — aggregate. Without the aggregate, we could not survive the way we do now.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.