Town Council and mayoral candidates in Asheville’s closest neighbor to the north, Woodfin, know that growth is inevitable, and the crowds are coming. The threat of uncontrolled growth led to a dramatic turnover on Council two years ago, and more fresh faces have emerged to run as the old guard steps down.

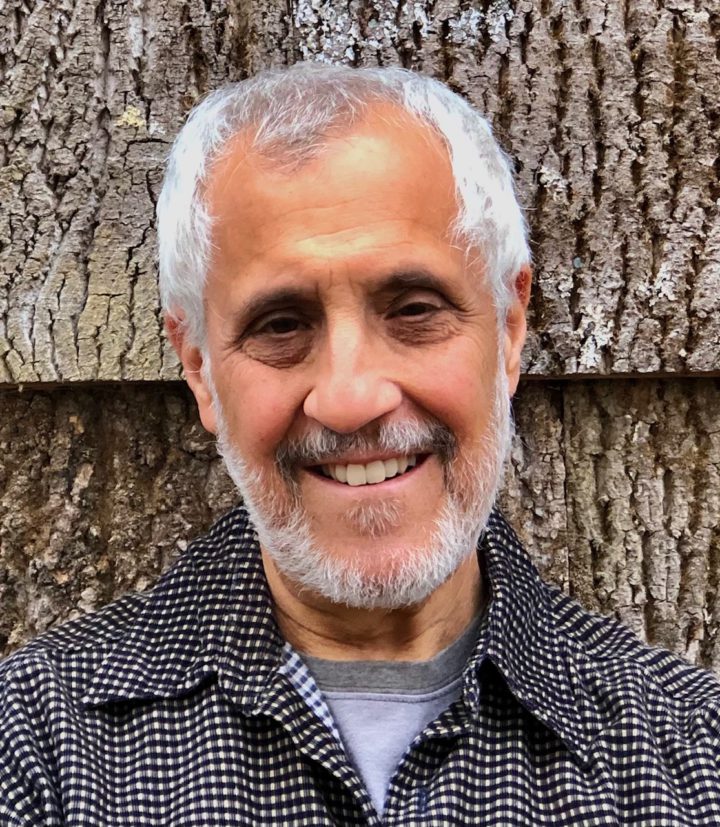

In 2021, as part of a wave that swept in three new council members, Jim McAllister won the most votes ever cast for a candidate for Woodfin Town Council inspired by opposition to The Bluffs, a massive development near the Woodfin-Asheville line. This year, the current vice mayor is running to replace longtime Mayor Jerry VeHaun, who is retiring after 20 years in the position.

“I intend to do the job of mayor very differently. The current Council members and all of the candidates running for Council have told me they’re absolutely in favor of me taking a different role. It’s going to be one of cheerleader, working to recruit businesses, developers, retailers and new neighbors,” says McAllister, who moved to Woodfin in 2019.

For most of his tenure, VeHaun operated as a mayor administrator until the Town Council opted to change from a strong to weak mayor form of governance in 2021, taking away the mayor’s vote on Council and relegating the position to essentially be the public face of the town.

McAllister says that if elected, he intends to use the opportunity to aggressively recruit private businesses to town and convince young people to get involved with civic matters. He wants to form volunteer working groups of residents to do research on how technology such as artificial intelligence can more efficiently run the town’s Police Department and figure out how to entice more developers to build affordable housing in Woodfin.

“A lot of the old-time Woodfiners don’t want anything to change. And I feel sorry for them because you can’t stop change. We’re not going to ruin the town or let it be paved in condos, but change is coming, and it’s important that we manage it. To do that, it’s going to take young people,” he says.

McAllister’s opponent in the mayoral race, Jason Moore, is not one of those old-time Woodfiners, either. He moved to the west side of Woodfin after retiring from the Marine Corps in May.

He touts his varied experience as a “problem solver” over 20 years working in the federal government as the greatest strength he could take to the mayor’s office.

On most issues, Moore says VeHaun did a good job, and if elected, he plans to keep the status quo. Moore does agree, however, with development rules the new guard on Council passed, including a steep-slope ordinance, conditional zoning rules and guardrails for short-term rentals, a sentiment echoed by all of Woodfin’s Council candidates.

Town Council and managing growth

The only incumbent running in the Council race has yet to be elected. Elisabeth Ervin was appointed to replace longtime Council member Jim Angel in February 2022 after Angel resigned for health reasons.

Ervin has lived on the north side of town since 1994 and retired as a federal deputy chief probation officer for the Western District of North Carolina in 2014.

Like others running for Council, Ervin sees Woodfin’s greatest challenge as managing the coming waves of growth and wants to help ensure the town doesn’t get stuck in the past as new residents move in.

“There is much in the past to cherish, but we need to make certain the town is ready for an influx of residents with both housing and employment opportunities,” she says.

To that end, she is most excited about the potential to establish a Woodfin Business Association focused on recruiting new businesses to town, showcasing Woodin’s amenities and real estate.

Kenneth Kahn, who has been in Woodfin for five years, says his experience serving on the Buncombe County Planning Board and Woodfin’s Comprehensive Plan Steering Committee gives him a perspective into development in Woodfin that is invaluable.

Kahn has a vision for mixed-use pocket neighborhoods of affordable workforce housing that include services and retail in the neighborhood. He thinks that would help recruit a younger working population — including families — to town, increasing the tax base without raising taxes.

Kahn acknowledges that any development projects need community buy-in, and he is aware of the potential gentrification that can result from bringing large mixed-use developments to town.

“The real challenge is to manage the growth so that we’re not dispossessing anybody, we’re not evicting people, we’re not forcing them to live in [communities that are] different [from what] they want,” he says.

Still, he remains confident that space can be found in town for inventive mixed-use developments.

Woodfin Wave

Johanna Young, who first moved to the area in 1990 to attend UNC Asheville, wants to use her master’s degree in public health education and background in biology to ensure Woodfin can marry its economic development desires with sound stewardship of its environmental resources, namely the French Broad River.

The river runs south to north through the western part of Woodfin, and its banks are dotted with a mix of industry and river parks.

Recently, the town secured nearly all of the $33.1 million needed for a greenway and blueway project that includes a man-made whitewater wave in the French Broad River at Riverside Park, greenways along the river and Beaverdam Creek and renovations to recently acquired Silver-Line Park. Construction at Riverside Park is expected to begin next spring, with the wave completed next summer, says Shannon Tuch, Woodfin town manager.

Residents are bracing for a wave of tourists from the developments, and some candidates wonder if the town’s infrastructure can handle the inevitable influx.

Council candidate Josh Blade says while the whitewater wave is an exciting investment, he questions whether it was wise to spend so much of the town’s resources to bring it to fruition. According to Tuch, the town spent more than $5 million of its own money on the project.

Similarly, Moore, the candidate for mayor, wonders if there will be unintended consequences of bringing so many people into Woodfin, such as more traffic on Riverside Drive and increased pollution in the already impaired French Broad River.

“Where are they going to park? How are they going to get there? Where are they going to stay?” asks McAllister. “I don’t want everybody coming to use the wave staying in Asheville and spending all their money in Asheville. That’s why I want to lead the charge in finding restaurants and other merchants and hoteliers to come to Woodfin to get us ready for these tens of thousands of people who may be coming to town.”

Stormwater fee rankles residents

While much of the town’s focus is on the future, changes in the present have left some residents dreaming of the past.

This summer, Woodfin enacted a stormwater fee for the first time. Its implementation did not get off to a good start. Tuch says the bills mistakenly went out to hundreds of residents without a letter explaining the new fee, creating an uproar.

The town was issued a violation by N.C. Department of Environmental Quality in 2019 for not meeting its responsibilities under a stormwater permit issued in 2017. The town, under previous management, ignored the notice, leading to penalties in early 2022, which the town has appealed.

Tuch took the town manager position in March of that year and immediately submitted a draft stormwater plan to correct its previous mistakes. Part of that plan was to impose stormwater fees to help pay for the program, issued to property owners based on the amount of impervious surface on a property.

Some residents consider the fee unfair and unjust.

Chip Parton, who lives in a neighborhood west of the river that was annexed in 2010 despite neighborhood opposition, says that part of town doesn’t get enough town services to justify its taxes.

On Olivette Road, which runs along the town limits in one section, Parton says the only difference between properties on each side of the street is the color of their trash cans — green and blue WastePro cans in the county, black cans inside Woodfin town limits. Otherwise, there is no difference in services for the Woodfin residents who pay extra taxes in a town they never wanted to be a part of in the first place, Parton says.

Incensed over the new stormwater fee, Parton circulated a petition among neighbors — now more than 200 signatures strong — asking the N.C. General Assembly to deannex their neighborhood.

Blade, one of two Council candidates who live west of the river (Kahn is the other, Moore also lives west of the river) issued the strongest rebuke of the stormwater fees of all the candidates running, saying he would repeal the fee and look for alternate ways to maintain the stormwater system.

“It is not the residents’ fault that the town spent all their money elsewhere, ignored the fact that these systems needed fixing, then waited until the [state] forced them to do something before passing that burden onto the residents themselves,” Blade says.

Tuch and McAllister argue that the fee is necessary to adhere to the town’s permits, and maintenance of the town’s drains will improve with the fee in place.

Regardless, Parton says, candidates’ response to the stormwater fee could make a difference in the ballot box.

So the storm water fine required hiring a 80k per year employee.