Next time you’re sitting in traffic on Interstate 240 or attempting to make a nearly impossible left turn on Merrimon Avenue during rush hour, just know that it’s not your imagination: Asheville is getting more crowded.

The constitutionally mandated decennial count of every person living in the United States that is the U.S. census was completed in 2020. And the results show that Asheville’s population has grown 13.4% since 2010, from 83,393 to 94,589 residents. Buncombe County saw a similar increase of 13.1%, from 238,318 residents in 2010 to 269,452 tallied last year — the largest gain in all of Western North Carolina.

While North Carolina’s population grew about 9.5% overall, 51 of the state’s 100 counties lost residents, primarily in rural areas. WNC was mostly an exception to that rule, with many of the area’s rural counties growing in population. Macon County, for example, grew by 9.1%, while Henderson gained 8.9% and Jackson 7%.

Census data also shows that Buncombe County grew somewhat more diverse. The county’s proportion of people who identify as white declined from 87.4% to 81.2%, while those who identify as biracial grew from 2.1% to 7%. The Hispanic or Latino population also increased from 6% to 8.1%. (The Census Bureau cautions that the latest numbers may reflect changes in how last year’s census asked about race; people were allowed, for the first time, to check more than one box when self-identifying, which may make comparisons with previous years inaccurate.)

The demographic data tells stories on their own, but politicians and analysts are turning their attention to what comes next: redistricting. The N.C. General Assembly must take census results into account as members create new voting district boundaries that reflect the state’s population growth and follow strict legal criteria.

Blurred lines

Redistricting, like the census, occurs every 10 years. Census data shapes boundaries for races in the U.S. House, as well as the General Assembly, because each district is required to contain a roughly equal number of voters. The three districts for the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners follow those for the N.C. House and would change if those district lines shift. However, census data will not impact Asheville City Council, which voted in October 2019 to reverse a district election system sponsored by Republican Sen. Chuck Edwards.

Chris Cooper, a political science professor at Western Carolina University, says that the General Assembly is required by a 2002 state Supreme Court decision to use the Stephenson Criteria. The guidelines ensure that state legislative districts comply with the “whole county provision” in North Carolina’s constitution. All 100 North Carolina counties are grouped into clusters, consisting of either a single county or a number of adjacent counties, based on population equality in a way that minimizes the number of county splits.

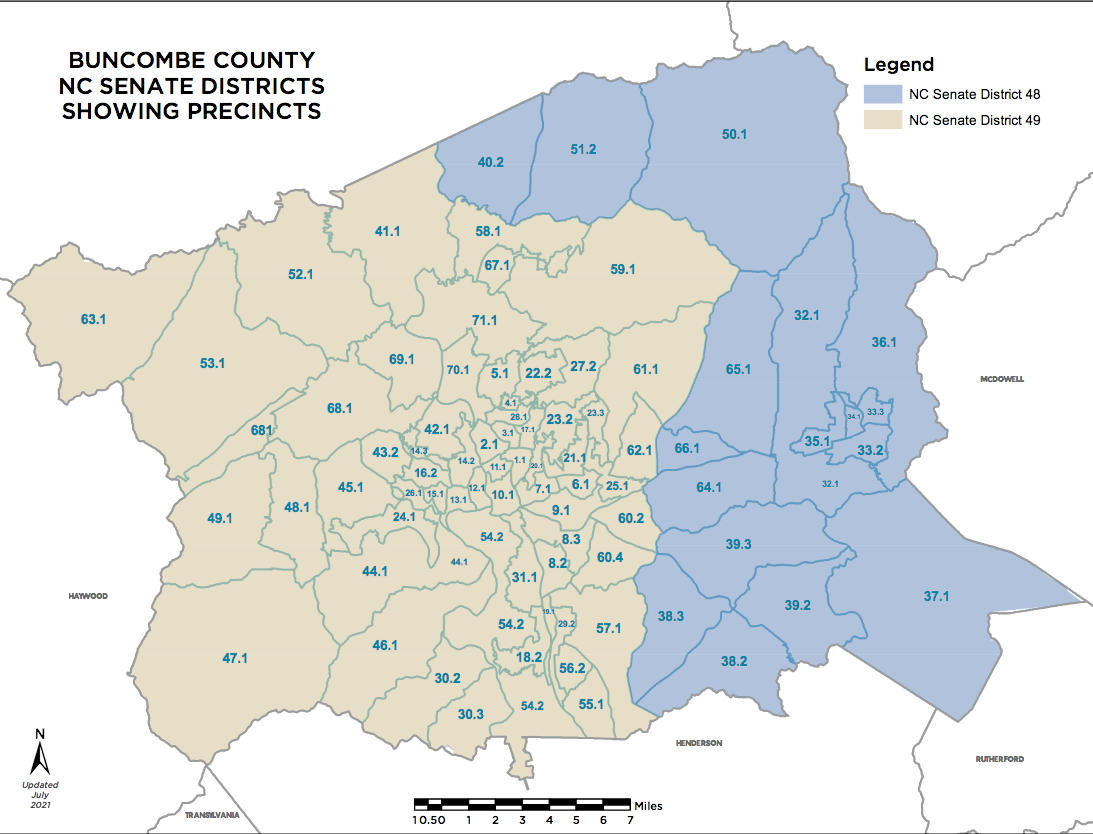

Although Cooper says those criteria are unlikely to significantly change Buncombe’s state House or Board of Commissioners districts, larger shifts could happen in Senate representation. Buncombe is currently clustered with Henderson and Transylvania counties to create Senate Districts 48 and 49. District 48 holds the eastern third of Buncombe, along with Henderson and Transylvania counties, while District 49 contains Buncombe’s remainder.

Because of the region’s population growth, Cooper says that Stephenson provisions require the General Assembly to create a new grouping for the region, which could have new political implications. Edwards currently represents District 48, while Democrat Julie Mayfield holds District 49.

“Buncombe might be paired with Henderson and Polk, or Buncombe might be paired with Burke and McDowell [counties],” Cooper says. “That’s going to produce some differences in the state Senate regardless of what the answer is. With that said, there’s no doubt that Burke and McDowell lean more heavily Republican than Henderson and Polk.”

Ashley Moraguez, a political science professor at UNC Asheville, says the most predictable change coming to North Carolina is the addition of a new representative in the U.S. House — and therefore a new congressional District 14. The addition of a new district, which will most likely be centered in the Triangle region, will also force other districts to shrink, including WNC’s District 11, currently represented by Republican Rep. Madison Cawthorn.

Cooper adds that since N.C. 11 grew in population, it would need to downsize anyway.

“[General Assembly members] can completely redraw things in some ways that we don’t expect, which is possible. But if they were to keep the basic shape of the 11th, one option would be to get rid of Avery and Mitchell counties and then slice back a little bit of Rutherford County,” Cooper postulates. “So we’ll see some shifts. We don’t know how big of a shift.”

Unlike state Senate and House districts, congressional lines don’t have to follow the Stephenson rules, Cooper adds. The General Assembly thus has more leeway in drawing those boundaries and splitting counties to do so.

A fiery history

The last time North Carolina embarked on redistricting, following the results of the 2010 census, it became a national example of how wrong the process can go, according to Moraguez. “The past decade has been particularly controversial, contentious and messy when it comes to redistricting in North Carolina as a whole,” she says. “Our state has essentially been a lesson in what not to do when it comes to redistricting.”

Typically, a state only draws new political maps once a decade. However, North Carolina has had three different sets of districts since 2010 due to litigation around Republican lawmakers’ engagement in gerrymandering. The first set, developed in 2011, was struck down by a federal district court in 2016 as racially discriminatory.

But those lines, which divided Asheville and Buncombe County between Districts 10 and 11, were in place for the 2012 U.S. House elections. By diluting the area’s heavily Democratic vote, Cooper explains, Republican mapmakers all but assured that then-Rep. Heath Shuler, a “Blue Dog” centrist Democrat, couldn’t win his District 11 seat for a fourth term.

Shuler retired rather than seek reelection, paving the way for political unknown Mark Meadows. The Republican won the 2012 general election with 57.4% of the vote against his Democratic challenger, Hayden Rogers. Meadows was reelected three times before leaving Congress to become chief of staff to former President Donald Trump in March 2020.

“I think it’s no exaggeration to say that, whether you call it redistricting or whether you call it gerrymandering, the way the 11th Congressional District was drawn led directly to the rise of Mark Meadows,” Cooper explains.

The General Assembly redrew those maps in 2016, but in 2019, a state court rejected the boundaries as an unconstitutionally partisan gerrymander that favored Republicans. Lawmakers thus developed a third set of maps going into the 2020 election, which recombined Asheville and Buncombe County back into District 11.

Even after that Democratic stronghold was united in the district, however, Cawthorn handily won his election in 2020, taking 54.5% of the vote in a four-way contest with Democrat Moe Davis, Libertarian Tracey DeBruhl and Green Party candidate Tamara Zwinak.

Could Asheville and Buncombe County again be split in a way similar to that in 2010’s map? Kelly Fowler, co-chair of voter services for the nonpartisan League of Women Voters, says that’s unlikely for two reasons.

“One, [the General Assembly’s] criteria is to try to keep counties whole to the extent possible,” Fowler explains. “Two, the state of North Carolina spent almost $11 million over the course of 10 years in litigation based on the 2010 map. I think they know that people are paying much closer attention now.”

Cooper and Moraguez say they agree with that assessment. But given how important district lines are to North Carolina’s balance of power, they predict that more litigation will accompany the resulting maps — whatever the results may be.

On the horizon

Fowler says that draft maps will most like be released by the General Assembly at the end of September. Residents can then comment on the drafts in a series of forums to be held throughout the state. WNC’s forum will take place at Western Carolina University on Tuesday, Sept. 21, at 5 p.m. in Jackson County, although Fowler says that the League of Women Voters is pushing for forums to take place in each of the existing U.S. House districts. Comments can also be submitted on the legislature’s website.

Ultimately, says Moraguez, state legislators will have the final say, because state law forbids the governor from vetoing the maps. And while Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper controls the executive branch, Republicans lead the legislative branch; the new maps will require only a simple majority in the House and Senate. “The majority party has a lot of leverage here,” she says.

While no explicit deadlines are in place for congressional redistricting, Fowler notes that the pandemic delayed the release of 2020 census data for several months, meaning that the General Assembly has a much tighter window than usual for completing the new maps ahead of the 2022 election filing deadline in December. Despite that shortened time frame, she says, public participation is crucial to ensuring fair elections — and hopefully fewer lawsuits — over the next decade.

“We have seen North Carolina be one of the most gerrymandered states in the country. Both sides do it. Maryland has been in court because Democrats have gerrymandered. So it is a nonpartisan issue,” Fowler says. “We truly believe that voters should pick their representatives, not the other way around. Representatives need to be accountable to the people, and extreme partisan or other gerrymandering means that your voice just doesn’t count as much. And these seats will be in place for 10 years.”

It creates a curious quandary for Republican leadership in Raleigh: having our colonial governor Chuck Edwards continue to represent some of Buncombe County provides justification for his colonial rule, but the most rational approach would be to expand Julie Mayfield’s district to cover more of the county.

On the federal level, I think Chris Cooper’s right that the basic shape of the 11th won’t change, and you’re more likely to see Patrick McHenry’s district redrawn to cover Gastonia and Morganton like it used to do.

They don’t need Lord BabyDocca to represent any of Buncombe County. He represents none of the city of Asheville, but he has a bill in the legislature forcing Asheville to move to an elected school board.

Just for the record, my post is not pro or con an elected board, just that the decision should be made by citizens of Asheville and not enforced upon us by the powers that be in Raleigh, especially since the powers that be in Raleigh are of the party that once believed in home rule until they got in power.

You’re right but you have to appreciate the irony of your statement “the decision should be made by citizens of Asheville “.

Yes, and the same must be said of the school board!

The county’s proportion of people who identify as white declined from 87.4% to 81.2%

Good Gawd! It’s true – they are trying to replace us!