Mary Beth Mackley was sitting in an open fishing boat with a wet tushy when inspiration hit.

“It was a beautiful day. I was in my blue jeans, and water kept coming into the boat. I had a wet seat all day,” recalls Mackley, who works as a nurse at Mission Hospitals. It was 1990, and she was salmon fishing on Alaska’s fabled Kenai River. “Here I was, uncomfortable, and my dream was to be in Alaska, and it kind of really just ruined my day. I said to myself, ‘If I just had some kind of waterproof shorts to put over my jeans!’ When I got back, I kept thinking about this and looked around and didn’t find anything at all like it.”

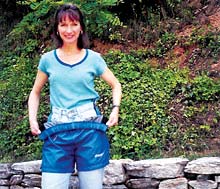

So, figuring that others might also like to maintain a dry derriere while communing with Mother Nature, Mackley created the “sit-upon shorts” (U.S. Patent No. 5,956,774), bearing the now-trademarked brand name “Craggy” after the popular stopping-off point along the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Here’s how the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office describes Mackley’s creation: “A shorts type garment, being joined and secured on the body of a wearer with closure flaps that are easily released at the hip and waist areas. The garment protects the buttocks area from environmental elements and is easily carried and donned. The garment comprises at least two layers. The outer layer acts as the primary barrier between the environmental elements and the wearer of the garment, especially providing protection from moisture. There is at least one inner layer to the garment, which can serve in a way to provide additional protection from environmental elements. This shorts type garment provides the wearer of the garment a means to adjust the garment for an appropriate fit.”

And while Mackley’s idea was ultimately deemed unique enough to merit a patent, the inventor herself is no anomaly. Western North Carolina is teeming with patented inventors and innovators—hundreds upon hundreds of them, working alone or for a company—who are either creating new products or improving existing ones. Asheville alone is home to 861 patent holders, according to the Patent Office database. (Although the database extends back to 1790, practically all the patents listed for Asheville and environs were issued within the past few decades.)

Several local people—most notably Carrol Buckner, inventor of the wood-burning Buck Stove—hold multiple patents or patents pending. Buckner has at least 23, according to the database.

“This area is just crawling with geniuses,” nationally renowned entrepreneur and business educator James Carland of Highlands told Xpress recently (see “The Biz,” Oct. 31).

Now what?

Securing a patent is an impressive feat, requiring not only a viable idea but as much as several years and many thousands of dollars in Patent Office and lawyer’s fees. Yet a patent is no guarantee of success. Mackley, for example, has found no takers to date, despite having pitched her product to numerous outdoor-clothing manufacturers, including Columbia, Nike, L.L. Bean, REI and others, she says.

Mackley filed for her patent on March 15, 1995. She finally received it Sept. 28, 1999, after two failed attempts to navigate the process without the help of a lawyer—a no-no for most people (especially neophytes), says local patent agent and former Washington, D.C., patent attorney Tom Champagne, who owns IP Strategies in Asheville. Mackley reckons she’s spent upward of $15,000 all told—including Patent Office fees, lawyer, travel and manufacturing some prototypes—with no payback so far, though she remains optimistic and plans to press on. Champagne says people may typically spend about $10,000 acquiring a patent. Less than half of those patents ever make the holder any money, he adds.

A patents primer

by Hal L. Millard

There are a number of legal mechanisms for protecting intellectual property. The copyright, designed to protect “original works of authorship” that are in a tangible form, confers the broadest protection. It applies to paintings, books, movies, choreographed dances (if the steps are written down), music, architecture and all other sorts of art. For a specified length of time, these works cannot be copied or reproduced without the copyright holder’s permission. In the United States, the protection extends for the life of the copyright holder plus 70 years (for works created after Jan. 1, 1978). If a company owns the copyright, the protection lasts anywhere from 95 to 120 years, depending on whether the work was ever published.

Other sorts of intellectual-property protection are much narrower in scope. Trademarks are for designs and phrases that businesses use to distinguish their product from those of other companies; trade secrets cover proprietary information that must be kept confidential in order for a business to profit from it (the recipe for Coca-Cola, for example).

But patents are the most complex and tightly regulated form of intellectual-property protection. Basically, they are copyrights for inventions, defined by U.S. patent law as “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof.” Unlike copyrights, patents protect an idea or design, rather than a tangible material form. Consequently, patents are much harder to obtain.

There are three types of patents:

1) A utility patent may be granted to anyone who invents or discovers a new and useful process, machine, article of manufacture, or material composition, or any useful improvement of an existing one. 2) A design patent may be granted to someone who creates an original, ornamental design for a manufactured article.

3) A plant patent may be granted to a person who invents or discovers and asexually reproduces a distinct variety of plant.

If patents are the most complicated type of intellectual-property protection, they’re also the most restrictive. To patent an invention, you have to satisfy a number of requirements. First of all, it must be substantially different from anything that’s already patented, has already been on the market or has been written about in a publication. You can’t even patent your own invention if it’s been on the market or been discussed in publications for more than a year.

The vast majority of inventions are actually not wholly new items but improvements to existing technology. The camcorder, for example, is essentially a combination of a video camera and a tape recorder, but combining them in a single unit was a unique idea—so innovative, in fact, that when Jerome Lemelson first submitted it to the patent office in 1977, it was rejected as an absurd notion. When the invention was eventually patented, it launched a flood of portable video machines. A search for the term “camcorder” in the Patent Office’s database turns up more than 1,000 separate patents. Thus, a modern camcorder is actually a composite of hundreds of other patented items.

Adaptations of earlier inventions can be patented as long as they’re not obvious—meaning that a person with standard skills in the area in question wouldn’t automatically come up with the same idea simply by examining the existing item. For example, you can’t patent the concept of a toaster that can handle more pieces of bread at once, because that’s merely making an existing invention bigger. To qualify for a patent, an idea must be more innovative.

Another condition is that the item must be “useful.” Generally speaking, this means that it serves a specific purpose and that it actually works. You couldn’t patent a random configuration of gears, for example, if it didn’t accomplish anything in particular. Nor could you patent a time machine unless you could construct a working model. Unproven ideas generally fall into the realm of science fiction, so they’re protected only by copyright law. The “useful” clause may also be interpreted as a prohibition against inventions whose sole use is for illegal or immoral purposes.

All a patent really does is give the patent holder the right to prevent others from producing, selling or using the item. For the life of the patent (20 years in the United States), patent holders can profit from their inventions by going into business for themselves or licensing the use of their creations to other companies. It’s up to the holder to actually enforce the patent; to enlist the government’s help, you must take those who infringe on your patent or copyright to court.

Business acumen is vital, says Carland. “You talk to any 10 people, and nine of them have a great idea for a new product; the curious thing is, how do you make that thing penetrate the market?” he observes. “That’s called commercialization, and understanding how to target the penetration of a market with a tangible product or an intangible service is an absolute skill that is tremendously valuable.” The Carland Academy teaches the art as well as the hard business basics of entrepreneurialism.

For the layperson, however, there are other challenges. It’s an arcane realm, and once you get past the basic improvements to quotidian items such as stoves, tires, furniture and sanitary napkins patented by area residents, many other local patents seem to border on the outright undecipherable.

Consider these examples from the database (all locally held): “Bisaminophenyl-based curatives and amidine-based curatives and cure accelerators for perfluoroelastomeric compositions”; “Algorithmic design of peptides for binding and/or modulation of the functions of receptors and/or other proteins”; “Method for detection of bromine in urine using liquid chemistry dry chemistry test pads and lateral flow”; “Treatment of polyamide with gas phase of acid anhydride or amine”; “Process of making a multiple domain fiber having an inter-domain boundary compatibilizing layer.”

Jeepers peepers

Although many patent holders never find commercial success, some do hit pay dirt—whether through simple ingenuity, sublime serendipity or a combination of the two.

Say hello to Peepers Puppet.

After the Buck Stove and the tread design on your set of Goodyears—the latter courtesy of Asheville resident Kevin Alan Reid, who’s listed as co-inventor on a slew of tire patents—perhaps the most ubiquitous product from a local patent holder is Peepers Puppet (U.S. Patent No. D366,297) the brainchild of Asheville puppeteer Hobey Ford.

Chances are you’ve seen this simple finger puppet somewhere; you may even own one, especially if you have small children. It’s simply a set of molded-foam-and-thermal-plastic eyeballs with an arched metal base that can be worn on a person’s finger to form an instant puppet.

That’s pretty much it. But Peepers, which costs about 50 cents to produce and sells for $3, grosses Ford around $50,000 annually and nets upward of $20,000—a nice supplement to the income from his main business, Hobey Ford’s Golden Rod Puppets. Peepers is manufactured by A&M Tool and Molding Corp. in Arden.

As a puppeteer, Ford has made his own puppets for years, and he cooked up the first Peepers prototypes at home. But the inspiration came from French mime Yves Joli (who Ford says is the first performer credited with using only their hands as a puppet) and the legendary Jim Henson (who used to rehearse The Muppet Show with Ping-Pong balls on his hands as stand-ins for characters such as Kermit the Frog). “It’s sort of an old idea,” Ford explains.

Ford’s children were also a major catalyst. “Basically, my kids wouldn’t let me wash their hair,” he reveals. “My wife said, ‘You’ve got to figure something out,’ because they hated shampoo. So I made these little eyeballs, and they would let the little puppet character wash their hair. So that’s how they came to be.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

“[Peepers] got really popular for about two or three years, and I had it in mall chains all around the U.S.,” says Ford, who received his patent in 1996. “It’s just this unlikely little set of eyeballs that fits on your hand like a ring. … This little invention, though, has gone way beyond what I could have ever done. It’s gone places I’ve never been. We get orders from all parts of the globe. … It’s been used in two Broadway plays. I also heard there’s a Mexican weatherman on television who’s famous and uses them in Mexico City. And there’s a sportscaster, some guy on television in the Netherlands, who uses them. They just turn up in weird places.”

Peepers was even the inspiration for a Nickelodeon TV show for preschoolers using a knockoff character called Oobi “that every 3-year-old probably knows,” says Ford.

While patented, Peepers is not copyrighted, so Nickelodeon and others are pretty much free to use Peepers as they please, so long as they don’t try to sell knockoffs. That’s OK with Ford.

“It’s like free advertising,” he says. “When Oobi came out, I was like, ‘Uh-oh.’ But then I thought, ‘No, this is a good thing.’ So people see [Oobi], and then when they find my toy they come after it.”

Who’s counting?

While many local patent holders are just plain folks smitten by a single idea they feel compelled to pursue, others hatch ideas and create inventions for their employer. Although WNC’s once-dominant manufacturing base is now a shadow of its former self, many local patent holders whose inventions are “assigned” to various corporations continue to pump out patents at prodigious rates.

Sterling Vaden, vice president of engineering at the Swannanoa-based SMP Data Communications, is one of the area’s more prolific industrial-patent holders. Vaden says he has so many, in fact, that he has difficulty keeping track.

Vaden is hardly a household name, but his inventions—most notably quantum improvements to the modular jack (U.S. Patent Nos. 5,299,956; 5,310,363; 5,911,602; and 6,663,419)—are among the key innovations that make today’s high-speed, broadband data communications possible. SMP manufactures the jacks and also licenses the technology to other manufacturers. The latest improvements make possible the once-unimaginable transmission speed of 10 gigabits per second—akin to moving up from a bicycle to a Ferrari.

“Only a couple of years ago, video on demand over the Internet idea was kind of a laughable thing, and now already people are doing that,” says Vaden, adding that 100 gigabits is the next hurdle to jump.

The significance of Vaden’s work is not lost on the company’s leader.

“What’s interesting is the fact that this little company that sat here for so long is the basis, the backbone, for the revolutionary, high-tech communications business,” General Manager Bill Reynolds told this reporter a few years ago in an interview concerning Vaden’s innovations. “None of it works without these little jacks in the wall.”

The products produced under Rudy Olsen‘s patents aren’t nearly as ubiquitous as Vaden’s. But Olsen’s work in improving the properties of the ceramic foam used to filter molten metals in the manufacture of everything from soda cans to aircraft engines (U.S. Patent No. 6,663,776) has made the Hendersonville-based Selee Corp. the world market-share leader in its field. The company’s technology is used by such giants as Alcoa, Ford, General Motors and John Deere to create metal products and components that are thinner, lighter, more efficient and less expensive.

“What you do, you take this filter at room temperature and pour molten iron over it, which is about 1,400 degrees centigrade—and it can’t crack,” says Olsen, Selee’s director of research. “So there is some very special design features about it. Then a head of about 50 pounds of iron gets built up, and it has to support that. We had an existing composition, but we re-formulated it and improved the strength by about 50 percent. Right now we believe we have the absolute best product on the market with that patent. It has the highest strength, and therefore customers get very low scrap [iron] rates.”

Olsen has several patents pending from a previous job and holds two patents with Selee. In addition to the above patent, a second patent with Selee has enabled the company to grab “about 80 percent of the aluminum-filter market in North America,” he explains. “So most of the aluminum cans you drink out of—and products like molding for windows, extrusions, aluminum foil, airplanes—a lot of that stuff has gone through our filters.”

Patently illegal

While many inventors might view a patent as a career or life milestone, Vaden and Olsen take their accomplishments in stride. Even though they’re the inventors of record, their employers own the intellectual property protected by the patents. For Vaden and Olsen, it’s just another day at the office.

“I didn’t really think about it that much,” says Vaden about his first patent. “It just felt like, ‘Oh, well, that’s great. I hope this thing works.’ I do get a little plaque, though.” That’s because there’s a whole cottage industry peddling products to new patent holders to commemorate their feat.

Olsen, on the other hand, says he was thrilled about receiving his very first patent. “The first one was a big deal,” he recalls. “Some company sent me a flier that had all kinds of plaques and stuff—all kinds of crazy stuff. There was this coffee mug; I thought to myself, I was the kind of guy that wouldn’t really do that kind of thing for myself. But I thought my grandfather might like a coffee mug with my patent emblazoned on the side of it. … It was a picture of the microstructure of the silica-carbide material, and that was what was printed on the side of the cup. I bought him that for Christmas; he used to show that to everybody that came by, that his grandson held a patent. But the second one? The excitement is greatly diminished.”

And it’s not like the companies that own the patents shower their employees with money or other goodies. Independent operators can often negotiate royalties, but “if you’re an employee working for a company, they usually dictate what they are willing to reward for getting a patent,” says Vaden. It could be nothing; it could be $1 or $1,000, but typically the patentee never shares directly in the wealth created by the patent that bears their name, he says. Reynolds, however, notes that firms such as SMP will spend considerably more time and money enforcing their patents than they do to obtain them in the first place. SMP keeps its patent lawyer busy, paying six figures annually to crack down on people—often in countries such as China and India—who steal their technology. Even Ford says he’s had to be diligent in his efforts to prevent Peepers knockoffs from being sold in this country.

“If I hadn’t had the patent, I couldn’t have stopped the importers from bringing [them] in,” notes Ford. “About two dozen companies got nailed on it,” and some retail chains, such as Target, voluntarily pulled the fake Peepers from their shelves.

But while Ford, SMP and others are fighting for their products in the marketplace, Mackley is still working and waiting just to get her shorts to market. She’s even tried to entice charitable-minded manufacturers with promises to donate a portion of her profits to causes they support.

“I’ve tried everything,” says Mackley. “I think I have the right idea; I just haven’t made the right contact yet. … I’ve tried to be generous, but I can’t find a taker. Anyway, I’m spilling my guts to you, so who knows? Maybe it will be worthwhile. I’ll just keep persisting.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.